This Vomiting Robot Is Really A Next-Generation Display Technology

Ha ha, there’s a robot that barfs! For science! While tech bloggers make endless sophomoric jokes about this seemigly Ig Nobel-worthy invention, it’s worth considering what “Larry” (as the vomiting robot is called) augurs for the future of anthropomimetic robotics.

Androids have fascinated us for centuries, and constructing an artificial person has been a dream and a dread since Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein. But as technology advances and humanoid robots enter the realm of reality, the “will they serve us or enslave us?” questions seem less interesting than the practical one that applies to every other kind of technology we’ve ever invented, from stone axes to microprocessors: that is, “what is this tool good for?”

As Rolf Pfeifer, the lead researcher on the ECCErobot project, put it to me when I interviewed him last year: “Why build a robot which is a very fragile and expensive copy of a human being?” Or, in Larry’s case, a crude copy of one particular (and gross) physiological reaction in a human being? To learn about ourselves, of course.

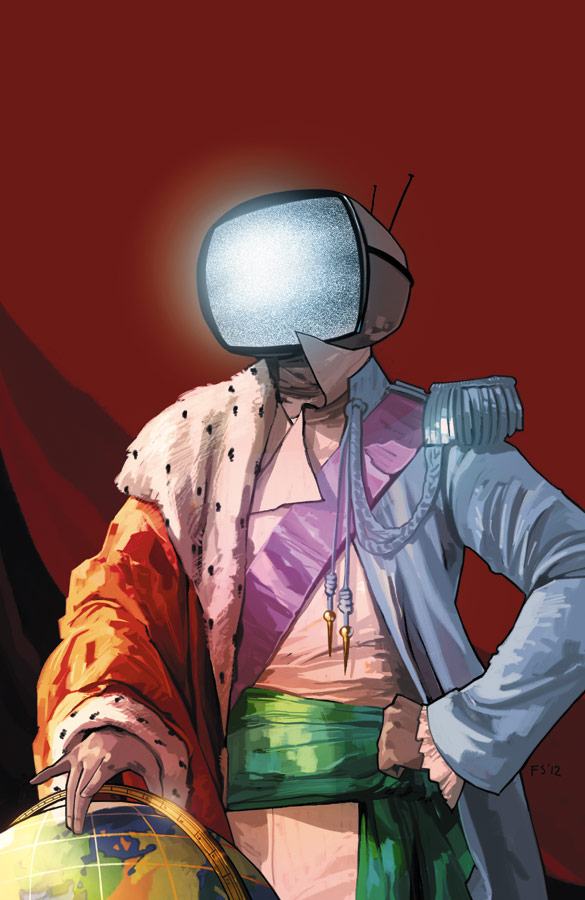

Androids, in short, are interfaces. And the more high-fidelity these interfaces become, the more useful they will be–not as butlers or soldiers, but as “screens” that display information about our own inner workings and make it more understandable and actionable.

Petman, the eerily lifelike walking droid manufactured by Boston Dynamics, may look like a Terminator prototype, but it’s actually designed to test chemical protection clothing for humans. ECCErobot began as a testbed to study how our brains control our floppy, fragile bodies. And Larry, god bless him, is basically a display technology for studying the contagious properties of aerosolized norovirus (a nasty bug that spreads from projectile vomiting).

Humanoid robots have much more in common with “gut on a chip” diagnostic models than they do with Asimo, Cylons or replicants. As UI designer Aza Raskin once said, “the human body is a terrible interface.” It’s opaque, confusing, messy, and ethically fraught. A vomiting automaton is simple, clear, and clean by comparison–as any well-designed display should be.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.