L.A. Cops Embrace Crime-Predicting Algorithm

A recent study suggests that computers could be better than seasoned police analysts at predicting when and where crime will strike next in a busy city.

Software tested in Los Angeles was twice as good as human analysts at predicting where burglaries and car break-ins might happen, according to a company deploying the technology.

When police in an L.A. precinct called Foothill division followed the computer’s advice—and focused their patrols within the areas identified—those areas experienced a 25 percent drop in reported burglaries, an anomaly compared to neighboring areas.

“We are seeing a tipping point—they are out there preventing the crime. The suspect is showing up in the area where he likes to go. They see black-and-white [police cruisers] talking to citizens—and that’s enough to disrupt the activity,” Sean Malinowski, a police captain in the Foothill division, said in a press webinar last week. The division has nearly 200,000 residents in a 46-square-mile area of the San Fernando Valley.

The software is built by a startup company, PredPol, based in Santa Cruz, California, and builds on computer science and anthropological research carried out at Santa Clara University and the University of California, Los Angeles.

The inputs are straightforward: previous crime reports, which include the time and location of a crime. The software is informed by sociological studies of criminal behavior, which include the insight that burglars often ply the same area.

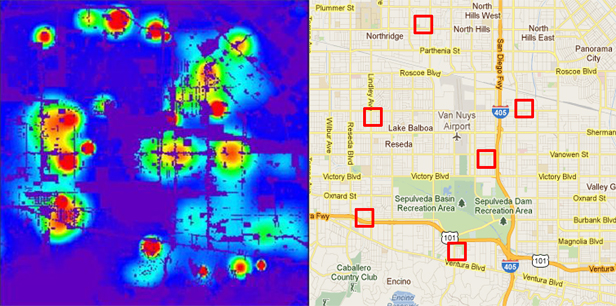

The system produces, for each patrol shift, printed maps speckled with red boxes, 500 feet on each side, suggesting where property crimes—specifically, burglaries and car break-ins and thefts—are statistically more likely to happen. Patterns detected over a period of several years—as well as recent clusters—figure in the algorithm, and the boxes are recalibrated for each patrol shift based on the timeliest data.

“The challenge, and what is really hard from the point of view of the crime analyst, is how do you balance crime patterns on different time scales. That’s where the algorithm has the edge, sifting through years of data,” says Jeff Brantingham, a company cofounder and UCLA anthropologist.

Proving that the algorithm really helped reduce property crime by 25 percent in Foothill is a difficult task. Police officers could, for example, know that stopping burglaries is a management priority, and shift resources and their attentions accordingly, regardless of the red boxes.

The company tested on previous data whether crimes occurred more frequently in the areas identified by the software, compared to boxes sketched by crime analysts. Between November 2011 and April 2012, in the crime-plagued Foothill district, the software predicted crime six times better than randomly placed boxes. Human crime analysts’ boxes were only three times better than the random boxes, according to Brantingham.

But whether the algorithm is right or wrong, it tends to reduce bureaucratic procedures and thus keep officers on the street, which by itself helps. Where police used to sit in daily meetings to plan where to patrol, they can now spend more time actually out on patrol, since the computer’s doing the planning. And if they do spook a would-be burglar into abandoning his plan, it means even more time on patrol, because the officer doesn’t have to leave his beat to process the suspect. “I don’t have them back writing a burglary report. I can have them have more minutes out on the mission. It is what we see happening,” Malinowski said.

The technology was previously tested in Santa Cruz, California. It has now been expanded to six Los Angeles areas inhabited by 1.1 million people, and is being expanded to other cities.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.