Knome Software Makes Sense of the Genome

A genome analysis company called Knome is introducing software that could help doctors and other medical professionals identify genetic variations within a patient’s genome that are linked to diseases or drug response. This new product, available for now only to select medical institutions, is a patient-focused spin on Knome’s existing products aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical companies. The Knome software turns a patient’s raw genome sequence into a medically relevant report on disease risks and drug metabolism. The software can be run within a clinic’s own network—rather than in the cloud, as is the case with some genome-interpretation services—which keeps the information private.

Advances in DNA sequencing technology have sharply reduced the amount of time and money required to identify all three billion base pairs of DNA in a person’s genome. But the use of genomic information for medical decisions is still limited because the process creates such large volumes of data. Less than five years ago, Knome, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, made headlines by offering what seemed then like a low price—$350,000—for a genome sequencing and profiling package. The same service now costs just a few thousand dollars.

Today, genome profiling has two main uses in the clinic. It’s part of the search for the cause of rare genetic diseases, and it generates tumor-specific profiles to help doctors discover the weaknesses of a patient’s particular cancer. But within a few years, the technique could move beyond rare diseases and cancer. The information gleaned from a patient’s genome could explain the origin of specific disease, could help save costs by allowing doctors to pretreat future diseases, or could improve the effectiveness and safety of medications by allowing doctors to prescribe drugs that are tuned to a person’s ability to metabolize drugs.

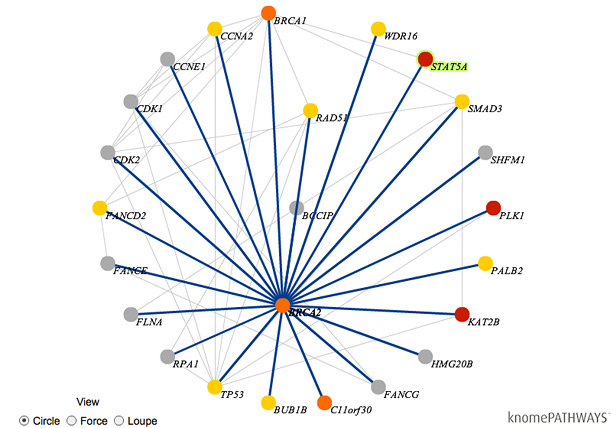

But teasing out the relevant genetic information from a patient’s genome is not trivial. To find the particular genetic variant that causes a specific disease or drug response can require expertise from many disciplines—from genetics to statistics to software engineering—and a lot of time. In any given patient’s genome, millions of places in that genome will differ from the standard of reference. The vast majority of these differences, or variants, will be unrelated to a patient’s medical condition, but determining that can take between 20 minutes and two hours for each variant, says Heidi Rehm, a clinical geneticist who directs the Laboratory for Molecular Medicine at Partners Healthcare Center for Personalized Genetic Medicine in Boston, and who will soon serve on the clinical advisory board of Knome. “If you scale that to … millions of variants, it becomes impossible.”

A software package like Knome’s can help whittle down the list based on factors such as disease type, the pattern of inheritance in a family, and the effects of given mutations on genes. Other companies have introduced Web- or cloud-based services to perform such an analysis, but Knome’s software suite can operate within a hospital’s network, which is critically important for privacy-concerned hospitals.

The greatest benefit of the widespread adoption of genomics in the clinic will come from the “clinical intelligence” doctors gain from networks of patient data, says Martin Tolar, CEO of Knome. Information about the association between certain genetic variants and disease or drug response could be anonymized—that is, no specific patient could be tied to the data—and shared among large hospital networks. Knome’s software will make it easy to share that kind of information, says Tolar.

“In the future, you could be in the situation where your physician will be able to pull the most appropriate information for your specific case that actually leads to recommendations about drugs and so forth,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.