A New Coating Promises the End of Smudges

German researchers armed with smoking candles have come up with a cheap and easy way to coat surfaces so that oil droplets bounce or roll right off. The advance could eventually lead to eyeglass coatings and tablet computer screens that can evade the mark of even the greasiest fingerprints.

Making surfaces able to repel fluids—whether water- or oil-based—is also important for industrial and biomedical applications. But it’s harder to make a surface that repels oil or organic solvents as opposed to water because oil has a far lower surface tension than water.

What’s required is a very specific type of surface roughness—akin to the branches of a budding tree—that achieves oil-repellency. This has been understood for some time, but it has been difficult to fabricate such a texture. Earlier work at MIT and elsewhere involved complex nanolithographic techniques.

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, in a paper published today in the journal Science, say they’ve come up with a simpler way, using a combination of candle soot and silica baked at just the right temperature.

First they held the glass slide over a heart-shaped candle (though any candle will do). This led to the deposition of soot on the slide—spheres of soot that were 30 to 40 nanometers in diameter, stacked loosely and producing the right kind of surface texture: about 80 percent empty and 20 percent spheres.

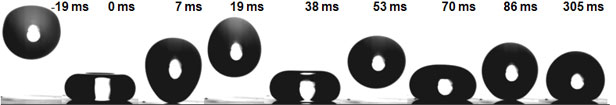

To protect the soot from washing away, they coated it with a silica shell 25 nanometers thick; to get rid of the black color of the soot, they baked the slide at 600 ºC, making it transparent. Afterward, they sprayed various oils—peanut oil and solvents—and took micrographs of these liquid droplets bouncing up and down like ping-pong balls.

The coating sticks to aluminum, steel, and copper, too. And because it has both oil- and water-repelling qualities, the material is said to be “superamphiphobic.”

Neelesh Patankar, a mechanical engineer at Northwestern University, says the work is an important step toward finding a commercially viable way to make such materials. “It has been known what surface chemistry as well as geometries would work” to repel oils, he says. “This work shows a good way to make such coatings with the right kind of practically relevant properties.”

There’s a surprisingly large need out there for surfaces that repel things. For instance, it could allow for building panels that repel water—or oily stains or residues—so efficiently that rain would wash them, making them self-cleaning. Or even biomedical products, including microfluidic technologies, that don’t get clogged by watery or fatty materials sticking to them. “I am looking for an eyeglass coating, but this could have important applications around medicine, too,” says Doris Vollmer, a materials scientist in the Max Planck group. “For many applications, people would like oil repellence. It’s not sufficient that something is water-repellent.”

While the researchers used candle soot, soot particles of similar sizes are available commercially, leading the way to potential manufacturability at high scale and low cost, she adds. The group is exploring commercial partnerships to advance the technology.

Ambarish Kulkarni, a mechanical engineer in the Advanced Nanotechnology program at GE Global Research—which also seeks superamphiphobic material surfaces—says the paper describes a “novel method” of making them. The GE researchers have found that such surfaces provide antifouling benefits inside gas turbines, potentially making them run more cleanly and efficiently.

Because the Max Planck method allows the materials to work at high temperatures, it “may open application areas previously unachievable,” he adds.

GE has several projects in this area, including an effort to instill superhydrophobic roughness on the surface of common thermoplastics used for things like product and food packaging.

One problem with the Max Planck coating is that, in contrast to roughened surfaces used for various water-repellant surfaces, it can get scratched or wear off. So the materials technology will need further refinements to make oil-resistant eyeglasses that are also truly scratch-resistant, Vollmer concedes. She is also working on ways to make the coating in chemical solutions, rather than the initially used vapor deposition method, which require high-temperature ovens.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.