White Worm Could Stop Bluetooth Viruses

Mobile phone viruses have been with us for some time. The first virus designed to spread via Bluetooth contacts first reared its head in 2004.

Called Cabir, it infects Series 60 mobile phones running the Symbian operating system and it is highly infectious. When computer security researchers first downloaded Cabir into a test device, they soon found their own phones under attack.

Today, computer security researchers use copper-shielded rooms where they can test how Bluetooth and WiFi viruses spread, without fear of an uncontrolled release.

But while these viruses continue to evolve, there has been relatively little work on how to stop them. That’s partly because viruses that spread by email or SMS message can be scanned relatively easily by a network operator using existing technologies (ie by comparing them to a database of known malware).

But short range viruses that spread from phone to phone via Bluetooth and wifi are more insidious. Mobile phones do not necessarily have the computing power to scan all incoming messages.

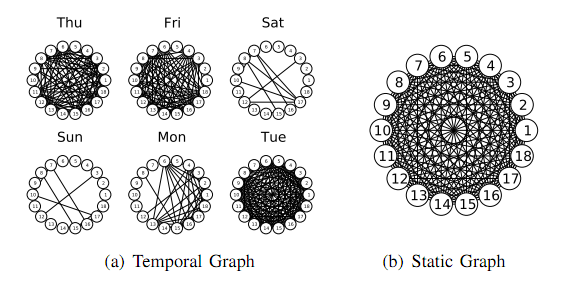

This problem is compounded by a crucial difference in the structure of the networks formed by short range wireless devices compared to the larger mobile phone network. Bluetooth links constantly change throughout the day in a way that mimics the pattern of face-to-face connections between humans. That’s hardly surprising given that Bluetooth has a range of just a few metres.

However, the mobile phone network is largely static, because calls have to routed through a centralised fibres.

The rapid change in the links between nodes has important implications. We looked at some of them earlier this year, such as the order in which contact occur. John Tang at the University of Cambridge in the UK and pals point out that dynamic nature of networks has been ignored in anti-virus strategies so far.

That looks set to change. Today, Tang and co reveal the new tricks they hope will smother this threat to dynamic networks.

One of the key differences between the way viruses spread on static and dynamic networks is the effect of the order in which infections occur. A seemingly trivial example is that it’s impossible to catch a virus from someone who is not yet infected. And once your link with that person is broken, as happens in dynamic networks, you’re safe. In a static network, by contrast, the links don’t break and you simply become infected later.

That has important implications for the spread of mobile malware. In any phone network, certain phones make far more connections than others. One traditional approach is to target these nodes with patches that prevent the spread of malware.

But in a dynamic network the constant rewiring means that these important nodes change too. So the best connected nodes at one instant may not be the best connected at another. Clearly, this has to be taken into account in any effective anti-malware strategy.

So what to do? Tang and co say the answer is to beat the malware at its own game by spreading any patch through the network via the same Bluetooth or WiFi routes that the virus is using. In that way, the patches should reach the best connected nodes automatically.

What’s more, since the dynamic network more or less exactly mimics the pattern of face-to-face interactions between humans, wireless viruses spread mainly during weekdays when most human contacts are made. But they are largely dormant during the night when few contacts are made

That’s significant because it means that any patch can catch up during the night. In fact, Tang and co show that their patch can spread at a rate that outpaces any virus.

Tang and co say this “white worm” approach can completely contain the malware in a limited amount of time, a claim that is rarely made of other anti-virus strategies.

That looks to be an interesting development in the cat and mouse race between the virus makers and and breakers. But it seems unlikely to be the last word. It can only be a matter of time before malware developers exploit the techniques outlined by Tang and co to spread their viruses more effectively through dynamic networks. And when that happens, the cycle will begin again.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1012.0726: Exploiting Temporal Complex Network Metrics in Mobile Malware Containment

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.