Slicing Up Silicon for Cheaper Solar

Solaria, a startup based in Fremont, CA, intends to cut the cost of solar panels by decreasing the amount of expensive material required. It has recently started shipping its first panels to select customers. This spring the company will begin production of solar panels at a factory built to produce 25 megawatts of solar panels per year.

Current high costs for the type of silicon used in photovoltaics have significantly driven up the price of conventional solar panels. Solaria’s cells generate about 90% of a conventional solar panel’s power, while using half as much silicon, says Kevin Gibson, Solaria’s CTO.

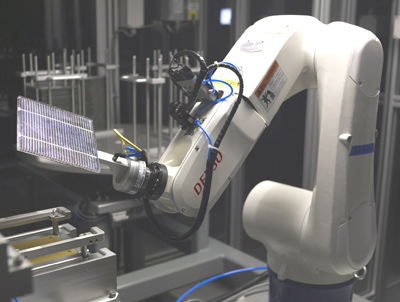

Ordinarily, the silicon in a solar panel spans its surface, collecting light from as much area as possible. But Solaria slices the silicon into thin strips and spaces them apart so that they only account for about half the panel’s area. A clear molded plastic cover collects light from the entire panel and funnels it to the strips of silicon.

This approach saves money because the total costs of the molded plastic, other extra materials, and added manufacturing steps still are lower than the cost of the additional silicon used in conventional solar panels. Solaria also reduces costs by using manufacturing equipment already developed for the semiconductor industry, thus avoiding expensive customized equipment. Gibson says Solaria’s first products will be economical enough to compete with panels produced by much larger companies, and that successive product generations will cost between 10 and 30 percent less than their competitors.

Silicon prices are high now. But the element is abundant, and already new facilities are coming on-line to produce more refined silicon. For Solaria is to be competitive in the long run, it will need to implement other cost-saving measures, especially improving the overall efficiency of its solar panels, says Tonio Buonassisi, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Such improvements are possible, Gibson says. For example, in conventional solar cells, wires for collecting current are placed on top of the cell, where they block some of the incoming sunlight. Solaria could place its wires between the strips of silicon, where they block no light. Because the wires wouldn’t need to be made thin to avoid blocking light, they could be sized to collect electricity more efficiently.

Solaria will be competing with many other companies that have developed ways to use less silicon. Evergreen Solar, based in Marlboro, MA, discovered a lower-waste technique of processing silicon. A group at the Australian National University developed slices of silicon set on edge to collect light and produce electricity. Stellaris, based in Lowell, MA, has created a technology that, like Solaria’s, uses low concentrations of light to reduce the amount of silicon needed.

Martha Symko-Davies, a senior research supervisor at the National Center for Photovoltaics at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, CO, says that Solaria’s approach may have an advantage over another type of technology that uses mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight by as much as several hundred times. While high-concentration approaches are promising, Symko-Davies says, they require complex tracking systems to keep the devices pointed directly at the sun. These systems add costs and can break down over time. Solaria’s approach does not require a tracking system.

To date, Solaria has raised $77 million to develop its technology, with the world’s largest solar cell maker, Q-Cell, acting as a primary investor.

Solaria’s long-term success still isn’t assured, Buonassisi says. But he also says the company’s technology “is an ingenious approach.” Ultimately, he adds, “the greater the diversity of technologies that are out there, the better.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.