How ubiquitous keyboard software puts hundreds of millions of Chinese users at risk

Third-party keyboard apps make typing in Chinese more efficient, but they can also be a privacy nightmare.

For millions of Chinese people, the first software they download on a new laptop or smartphone is always the same: a keyboard app. Yet few of them are aware that it may make everything they type vulnerable to spying eyes.

Since dozens of Chinese characters can share the same latinized phonetic spelling, the ordinary QWERTY keyboard alone is incredibly inefficient. A smart, localized keyboard app can save a lot of time and frustration by predicting the characters and words a user wants to type. Today, over 800 million Chinese people use third-party keyboard apps on their PCs, laptops, and mobile phones.

But a recent report by the Citizen Lab, a University of Toronto–affiliated research group focused on technology and security, revealed that Sogou, one of the most popular Chinese keyboard apps, had a massive security loophole.

“This is an app that handles very sensitive information—specifically, every single thing that you type,” says Jeffrey Knockel, a senior research associate at the Citizen Lab and coauthor of the report. “So we wanted to look into that in greater detail and see if this app is properly encrypting this very sensitive data that it’s sending over the network—or, as we found, is it improperly doing it in a way that eavesdroppers could decipher?”

Indeed, what he and his colleagues found was that Sogou’s encryption system could be exploited to intercept and decrypt exactly what people were typing, as they were typing it.

Sogou, which was acquired by the tech giant Tencent in 2021, quickly fixed this loophole after the Citizen Lab researchers disclosed it to the company.

“User privacy is fundamental to our business,” a Sogou spokesperson told MIT Technology Review. “We have addressed the issues identified by the Citizen Lab and will continue to work so that user data remains safe and secure. We transparently disclose our data processing activities in our privacy policy and do not otherwise share user data.”

But there’s no guarantee that this was the only vulnerability in the app, and the researchers did not examine other popular keyboard apps in the Chinese market—meaning the ubiquitous software will continue to be a security risk for hundreds of millions of people. And, alarmingly, the potential for such makes otherwise encrypted communications by Chinese users—in apps like Signal, for example—vulnerable to systems of state surveillance.

An indispensable part of Chinese devices

Officially called input method editors (IMEs), keyboard apps are necessary for typing in languages that have more characters than a common Latin-alphabet keyboard allows, like those with Japanese, Korean, or Indic characters.

For Chinese users, having an IME is almost a necessity.

“There’s a lot more ambiguity to resolve when typing Chinese characters using a Latin alphabet,” says Mona Wang, an Open Technology Fund fellow at the Citizen Lab and another coauthor of the report. Because the same phonetic spelling can be matched to dozens or even hundreds of Chinese characters, and these characters also can be paired in different ways to become different words, a keyboard app that has been fine-tuned to the Chinese language can perform much better than the default keyboard.

Starting in the PC era, Chinese software developers proposed all kinds of IME products to expedite typing, some even ditching phonetic spelling and allowing users to draw or choose the components of a Chinese character. As a result, downloading third-party keyboard software became standard practice for everyone in China.

Released in 2006, Sogou Input Method quickly became the most popular keyboard app in the country. It was more capable than any competitor in predicting which character or word the user actually wanted to type, and it did that by scraping text from the internet and maintaining an extensive library of Chinese words. The cloud-based library was updated frequently to include newly coined words, trending expressions, or names of people in the news. In 2007, when Google launched its Chinese keyboard, it even copied Sogou’s word library (and later had to apologize).

In 2014, when the iPhone finally enabled third-party IMEs for the first time, Chinese users rushed to download Sogou’s keyboard app, leaving 3,000 reviews in just one day. At one point, over 90% of Chinese PC users were using Sogou.

Over the years, its market dominance has waned; as of last year, Baidu Input Method was the top keyboard app in China, with 607 million users and 46.4% of the market share. But Sogou still had 561 million users, according to iiMedia, an analytics firm.

Exposing the loophole

A keyboard app can access a wide variety of user information. For example, once Sogou is downloaded and added to the iPhone keyboard options, the app will ask for “full access.” If it’s granted, anything the user types can be sent to Sogou’s cloud-based server.

Connecting to the cloud is what makes most IMEs successful, allowing them to improve text prediction and enable other miscellaneous features, like the ability to search for GIFs and memes. But this also adds risk since content can, at least in theory, be intercepted during transmission.

It becomes the apps’ responsibility to properly encrypt the data and prevent that from happening. Sogou’s privacy policy says it has “adopted industry-standard security technology measures … to maximize the prevention of leak, destruction, misuse, unauthorized access, unauthorized disclosure, or alteration” of users’ personal information.

“People generally had suspicions [about the security of keyboard apps] because they’re advertising [their] cloud service,” says Wang. “Almost certainly they’re sending some amount of keystrokes over the internet.”

Nevertheless, users have continued to grant the apps full access.

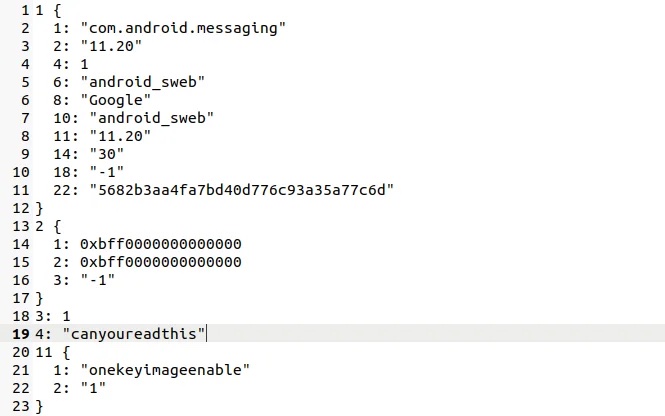

When the Citizen Lab researchers started looking at the Sogou Input Method on Windows, Android, and iOS platforms, they found that it used EncryptWall, an encryption system it developed itself, instead of Transport Layer Security (TLS), the standard international cryptographic protocol that has been in use since 1999. (Sogou is also used on other platforms like MacOS and Linux, but the researchers haven’t looked into them.)

One critical difference between the two encryption systems, the Citizen Lab found, is that Sogou’s EncryptWall is still vulnerable to an exploit that was revealed in 2002 and can turn encrypted data back into plain text. TLS was updated to protect against this in 2003. But when they used that exploit method on Sogou, the researchers managed to decrypt the exact keystrokes they’d typed.

The existence of this loophole meant that users were vulnerable to all kinds of hacks. The typed content could be intercepted when it went through VPN software, home Wi-Fi routers, and telecom providers.

Not every word is transmitted to the cloud, the researchers found. “If you type in nihao [‘hello’ in Chinese] or something like that, [the app] can answer that without having to use the cloud database,” says Knockel. “But if it’s more complicated and, frankly, more interesting things that you’re typing in, it has to reach out to that cloud database.”

Along with the content being typed, Knockel and his Citizen Lab colleagues also obtained other information like technical identifiers of the user’s device, the app that the typing occurred in, and even a list of apps installed on the device.

A lot of malicious actors would be interested in exploiting a loophole like this and eavesdropping on keystrokes, the researchers note—from cybercriminals after private information (like street addresses and bank account numbers) to government hackers.

(In a written response to the Citizen Lab, Sogou said the transmission of typed text is required to access more accurate and extensive vocabularies on the cloud and enable a built-in search engine, and the uses are stated in the privacy agreement.)

This particular loophole was closed when Tencent updated the Sogou software across platforms in late July. The Citizen Lab researchers found that the latest version effectively fixed the problem by adopting the TLS encryption protocol.

How secure messaging becomes insecure

Around the world, people who are at high risk of being surveilled by state authorities have turned to apps that offer end-to-end encryption. But if keyboard apps are vulnerable, then otherwise encrypted communication apps like Signal or WhatsApp are now also unsafe. What’s more, once a keyboard app is compromised, even an otherwise offline app, like the built-in notebook app, can be a security risk too.

(Signal and WhatsApp did not respond to MIT Technology Review’s requests for comment. A spokesperson from Baidu said, “Baidu Input Method consistently adheres to established security practice standards. As of now, there are no vulnerabilities related to [the encryption exploit Sogou was vulnerable to] within Baidu Input Method’s products.”)

As early as 2019, Naomi Wu, a Shenzhen-based tech blogger known as SexyCyborg online, had sounded the alarm about the risk of using Chinese keyboard apps alongside Signal.

“The Signal ‘fix’ is ‘Incognito Mode’ aka for the app to say ‘Pretty please don't read everything I type’ to the virtual keyboard and count on Google/random app makers to listen to the flag, and not be under court order to do otherwise,” she wrote in a 2019 Twitter thread. Since keyboard apps have no obligation to honor Signal’s request, “basically all hardware here is self-compromised 5 minutes out of the box,” she added.

Wu suspects that the use of Signal was the reason some Chinese student activists talking to foreign media were detained by the police in 2018.

In January 2021, Signal itself tried to clarify that its Incognito Keyboard feature (which only works for users on Android systems, which are more vulnerable than iOS) was not a foolproof privacy solution: “Keyboards and IME’s can ignore Android’s Incognito Keyboard flag. This Android system flag is a best effort, not a guarantee. It’s important to use a keyboard or IME that you trust. Signal cannot detect or prevent malware on your device,” the company added to its article on keyboard security.

The recent Citizen Lab findings lend further support to Wu’s theory.

The security risk is particularly acute for users in China, since they are more likely to use keyboard apps and are under strict surveillance by their government. (Wu herself has disappeared from social media since the end of June, following a visit from police that was reportedly related to her online discussions of Signal and keyboard apps.)

Still, other governments seem to have been paying attention to vulnerabilities with encrypted data transmission as well. A 2012 document leaked by Edward Snowden, for instance, shows that the Five Eyes intelligence alliance—comprising Canada, the US, Britain, Australia, and New Zealand—had been discreetly exploiting a similar loophole in UC Browser, a popular Chinese program, to intercept certain transmissions.

Beyond being targeted by state actors, there are other ways keystroke information acquired via keyboard apps can be sold, leaked, or hacked. In 2021, it was reported that advertisers were able to access personal information through Sogou, as well as Baidu’s keyboard and similar apps, and use it to push customized ads. And in 2013, a loophole was found that made multimedia files that users uploaded and shared through Sogou searchable on Bing.

These security problems are not unique to Chinese apps. In 2016, users of SwiftKey, an IME that was acquired by Microsoft that year, found that the app was auto-filling other people’s email addresses and personal information, as a result of a bug with its cloud sync system. The following year, a virtual keyboard app accidentally leaked 31 million users’ personal data.

Even though the specific loophole identified by the Citizen Lab was fixed quickly, given all these breaches, it feels somewhat inevitable that another security flaw in a keyboard app will be revealed soon.

As Knockel notes, using Sogou and similar apps always poses security risks, particularly in China, since all Chinese apps are legally required to surrender data if asked by the government.

“If that’s something that’s concerning to you,” he says, “you might also just reconsider using Sogou, period.”

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.