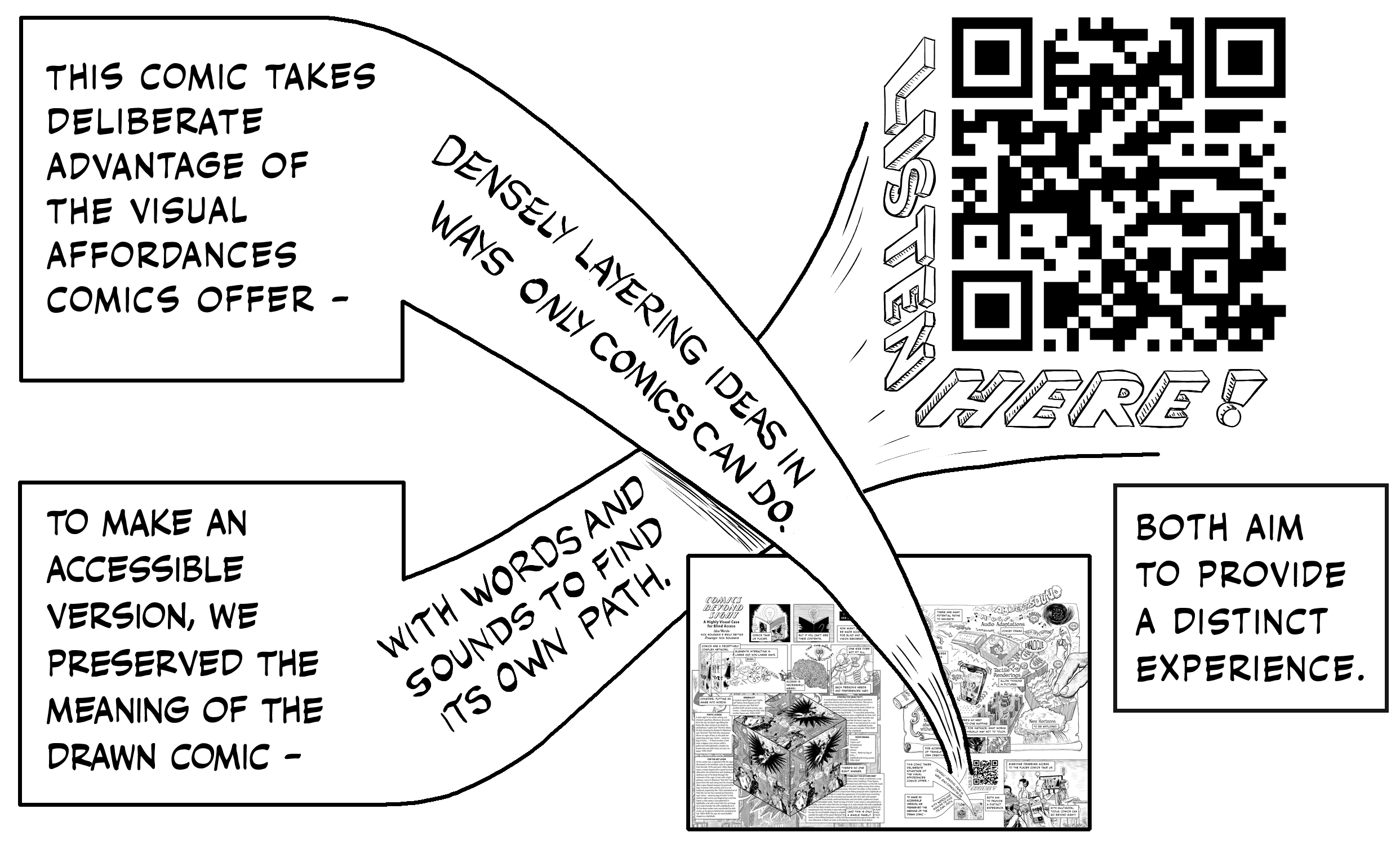

For an audio adaptation with descriptive text and for annotations, visit: https://spinweaveandcut.com/mitcomic/

![A single visually-busy larger panel. Text reads: “Consider putting an image into words…” A cube provides that single image, situated so that it presents three of its faces, all with the same picture showing: an illustration with Blackout, in bodysuit and large black cape, as he soars down from the sky over three members from the Bad Ideas Gang: Bad Idea, his henchman, and Felixa the catwoman. As he descends, Blackout says, “Lights out!” With a hardened face, the henchman exclaims, “Not him!” Blackout has whipped a spiky throwing blade, the shape of the Blackout symbol, to slice open the sack slung over the henchman’s shoulder and cash trails behind; Felixa in a full cat bodysuit holds a carpetbag and says, “mmm…I need my bag of tricks…” Bad Idea, leader of the crew and dressed in suit, tie, and bowler hat, says, “IDEA: RUN!” All three have light bulbs patterned on their clothing. From each of the six faces of the cube, three visible and three obscured, text boxes extend to provide six alternative styles of describing the panel, though the descriptive text can only be partially read behind captions and the cube. Labels illustrate a description style with a teaser of that style in the box. For example, “The minimalist: A masked caped figure says ‘Lights out!’ Below, three figures on the street: a person says ‘Not him!’ A lady in a catsuit - says, ‘mmm…I need my bag of tricks’ and another figure says, ‘IDEA: RUN!’” Second style “Poetic license” uses much more flowery language, provides subjective interpretation to describe character’s expressions. The third style: “For the art lover,” provides a lot of detail for someone who cares about visual aesthetics, more spatial information, more description of the artistic style. Fourth: “Striving for objectivity,” a bit awkward as it strives to only use neutral language and descriptors, it doesn’t guess at characters’ gender or race, doesn’t name expressions which could be open for interpretation. The fifth approach: “Radio drama” just uses the sounds and word bubbles to tell the story, “Swoosh!” “Lights out!” “[eeeoooeeeooo]” and so on. The final style, “Everything but the kitchen sink,” is as it sounds - an extremely detailed description that provides leaves no visual detail undescribed but becomes a bit cumbersome with how many words this then requires. A text caption at the bottom reads, “There’s no one right answer. (And this is only a single panel!)”](https://wp.technologyreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/workaround.jpeg)

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.