Getting in

I stumbled across an MIT application form from 50 years ago. You might be surprised by what has—and hasn’t—changed.

Until last fall, for as long as there had been an admissions office at MIT (nearly a century), it was located along the Infinite Corridor in 10-100. In the process of preparing for its move to its new home in the MIT Welcome Center, I stumbled across a rare archeological find.

Let me set the scene. One day in the summer of 2020—at the height of the campus covid-19 lockdown—I was permitted to visit the office to clear out any personal belongings. Prohibition style, I met a colleague with authorized campus access at an unmarked service door on the basement level of our building; we exchanged an awkward hello after having not seen each other in months. “Make it quick,” he said, as if we were orchestrating some kind of heist—and like a mysterious oracle, he vanished. It would be another year until I saw him again in person.

I didn’t make it quick after all. After a few minutes going through all my stuff, I spent a good hour rummaging around, taking full advantage of being in the office unsupervised. In an old metal filing cabinet, I found a trove of vintage MIT relics—everything from a set of vibrant neon Campus Preview Weekend brochures from the 1990s to stacks of old MIT Admissions marketing materials, and even a VHS tape titled “MIT: Mind and Hand.”

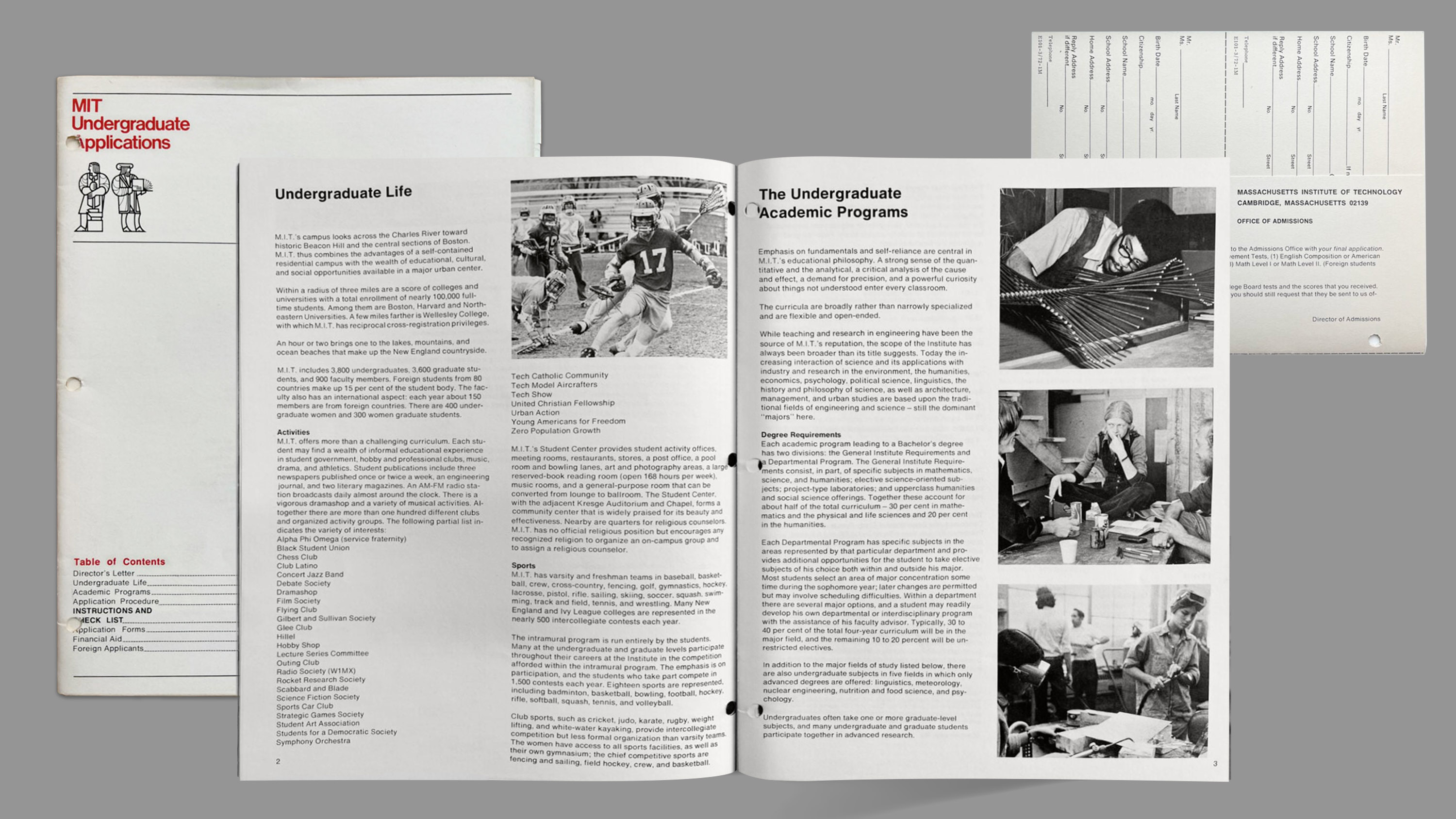

At the very bottom of the cabinet, I found the most exciting discovery of all: an original copy of the 1973 application to MIT, in perfect condition. It probably had been in the drawer since the 1970s.

Set in modernist International Style/Swiss typography—undoubtedly a product of legendary MIT designers Cooper and Casey—it is a 30-page printed booklet that would have been sent to interested students by first-class postal mail.

It begins with a letter from Peter Richardson, who served as director of admissions from 1972 to 1984; under his watch Stu Schmill ’86, our current dean of admissions, was admitted to MIT. Richardson’s letter expertly captures the MIT undergraduate education, even today.

We are pleased that the undergraduate educational opportunities at M.I.T. have attracted your attention.

Our basic approach to the purposes and goals of undergraduate education is characterized by a flexibility and openmindedness that was not evident a few short years ago. Faculty attention and student efforts focus on a style of educational encounter which emphasizes the context of the learning experience—the relationship of teacher and student—as contrasted with the subject matter of that experience. It is clear that no single style of education and no small set of alternative styles is appropriate for our student body with its extraordinary diversity in interests, abilities, preparation, and experience. The primary goal of the faculty is to assist students to arrive at the threshold of educational self-sufficiency and independence. We hope you will decide to join us in this endeavor ...

Several pages of information about MIT’s academic program and campus life follow. I was pleasantly surprised to see so many aspects of contemporary MIT reflected in these pages, including references to the Hobby Shop, Black Students Union, January Independent Activity Period, and MIT Symphony Orchestra.

The application advertises 33 majors for the bachelor of science degree, including a few no longer offered (Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering; History, Theory, and Criticism of Visual Arts). Though the number of undergraduate majors has nearly doubled since, the essence of the undergraduate program remains unchanged. I was struck by the clarity and concision with which it is described:

Emphasis on fundamentals and self-reliance are central in M.I.T.’s educational philosophy. A strong sense of the quantitative and the analytical, a critical analysis of the cause and effect, a demand for precision, and a powerful curiosity about things not understood enter every classroom.

And even in the 1970s, MIT was shining a light on its esteemed programs in the humanities and social sciences:

While teaching and research in engineering have been the source of M.I.T.’s reputation, the scope of the Institute has always been broader than its title suggests. Today the increasing interaction of science and its applications with industry and research in the environment, the humanities, economics, psychology, political science, linguistics, the history and philosophy of science, as well as architecture, management, and urban studies are based upon the traditional fields of engineering and science—still the dominant “majors” here.

Though we now release our Regular Action admissions decisions on Pi Day (March 14), that tradition didn’t arise until the 2000s. Early Action applications were permitted—and nonbinding then, too. But most applicants in the ’70s applied by the January deadline and heard back from MIT in early April.

Today I would tell applicants, “There’s no need to rush your application—apply when you are ready. Just do not wait until the last minute!” But the instructions in the 1973 application are a bit more direct: “Complete your application early and avoid the rush.”

The 1973 application form needed to be typed or written in ink, but it feels largely consistent with our current application. Just as we do now, it asks for a student’s “principal recent school and community activities and individual pursuits including participation in such areas as student government, athletics, music, religious and social work, and projects or hobbies.” Students are also asked to list jobs they’ve held and specify how they’ve spent their summers—and to “be reasonably specific on the allocation of time.”

Some of the “short answer” questions, however, do not have direct analogues on our current application.

16. Comment on a book that has affected your point of view, or some topic that you have read into extensively, apart from your school work.

Prompt 16 directs students to engage in meaningful self-reflection, leading them to discuss a topic they have explored outside of school work. It sends a clear message that MIT is interested in identifying students who cultivate intellectual interests on their own time—not only when they are required to. While this is still something we value at MIT, we don’t explicitly solicit this information on our current application.

18. In a paragraph or two discuss one of your interests that you would like to develop over the next four years.

Prompt 18 takes a more open-ended approach to a student’s long-term interests in a format that our current application doesn’t quite capture. Today, students often end up sharing long-term goals and interests—whether in a short answer, in an optional portfolio, or elsewhere—but prompt 18 intentionally invites them to share how their goals fit in with MIT in the longer term, past the point of admission.

This time capsule from 1973 does, of course, offer evidence of some pretty big changes at MIT. Its map of campus includes Ashdown House, Bexley Hall, Senior House, and Building 20—but is missing many buildings that had yet to be built, such as New House, Next House, the Stata Center, Simmons, and MIT.nano, to name just a few. The booklet’s financial aid information contains this stunning fact: tuition in 1973 was estimated at $2,900 per year.

I am left with the paradoxical sense that 1972 is somehow unfathomably distant and incredibly close. While much about MIT’s admissions process, the larger landscape of college admissions, and the composition of MIT’s student body has changed, our fundamental approach to sharing information about this place and identifying its future students has remained the same.

What essay questions will we be asking a half-century from now, if any at all? Is the future dean of admissions a current undergraduate? Will a researcher at CSAIL design an AI system that renders my job obsolete? Or will an admissions officer 50 years from now stumble upon my review of the 1973 application saved on an old hard drive somewhere in the MIT Welcome Center and laugh?

Jeremy Weprich is a senior assistant director of admissions at MIT. For pictures of the 1973 application, see the original admissions blog post on his archeological find.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.