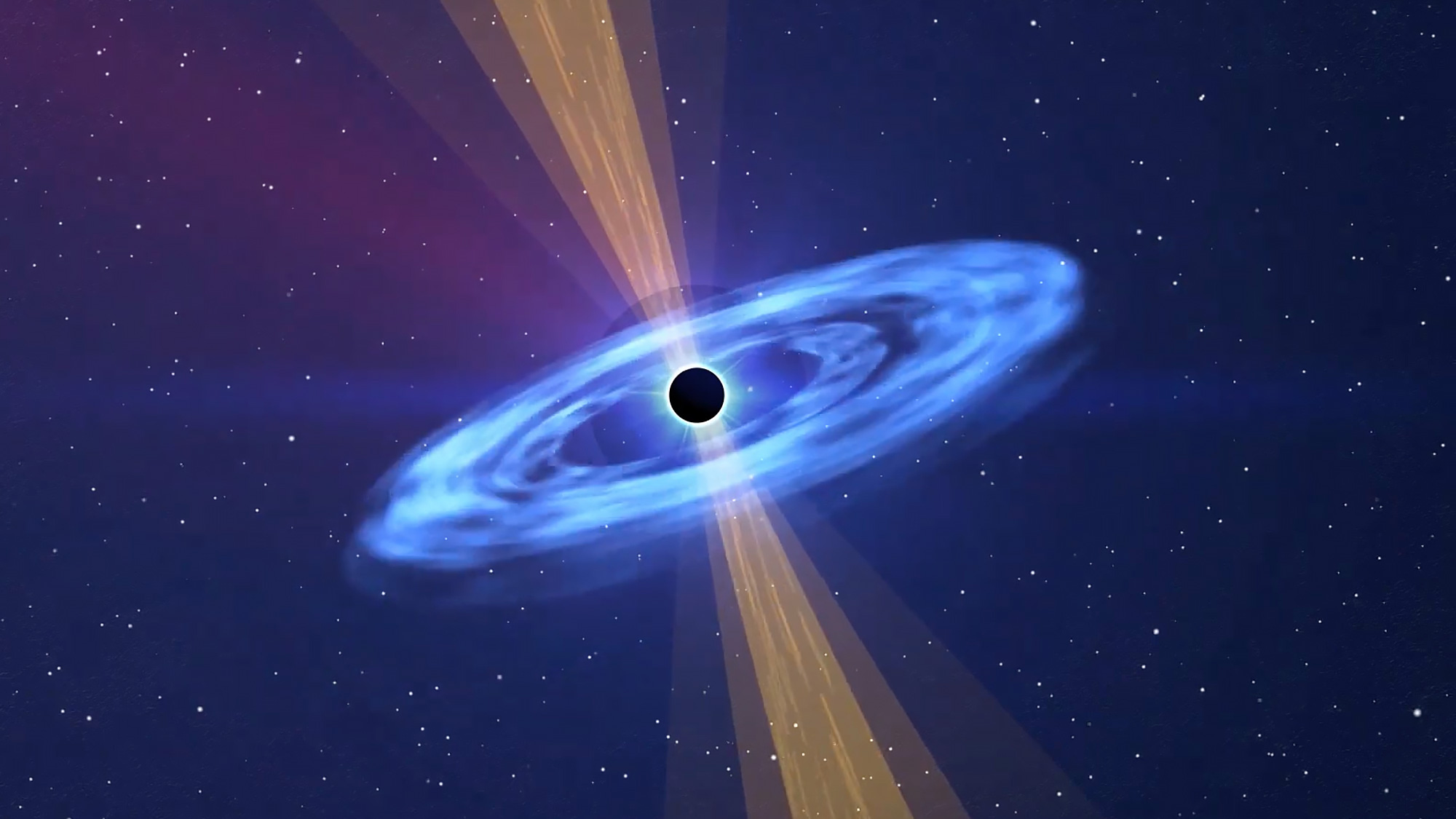

A black hole jet pointing right at us

The intensely bright light, halfway across the universe, could help us understand how supermassive black holes grow.

MIT astronomers and collaborators at NASA, Caltech, and elsewhere have identified the likely source of an extraordinary flash in the sky, giving off more light than 1,000 trillion suns, that was observed at the Palomar Observatory in California last year.

They report that the signal, named AT 2022cmc, likely comes from a relativistic jet of matter streaking out from a supermassive black hole at over 99.99% of the speed of light. They believe the jet is the product of a black hole that suddenly began devouring a nearby star in what’s known as a “tidal disruption event”: a shredded star creates a whirlpool of debris as it falls into the black hole, releasing a huge amount of energy in the process.

“It’s probably swallowing the star at the rate of half the mass of the sun per year,” says research scientist Dheeraj “DJ” Pasham, lead author of a paper on the discovery. “A lot of this tidal disruption happens early on, and we were able to catch this event right at the beginning, within one week of the black hole starting to feed on the star.”

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

At some 8.5 billion light-years away—more than halfway across the universe—it is farther away than any such event previously detected. The team says the reason it appears so bright in our sky is that the jet may be pointed directly toward Earth, causing a “Doppler boosting” effect similar to the amped-up sound of a passing siren.

As more powerful telescopes start up in the coming years, they will reveal more TDEs, which may help reveal how supermassive black holes grow and shape the galaxies around them.

“We know there is one supermassive black hole per galaxy, and they formed very quickly in the universe’s first few hundred million years,” says coauthor Matteo Lucchini, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

“That tells us they feed very fast, though we don’t know how that feeding process works. So sources like TDEs can actually be really good probes for how that process happens.”