When babies see faces

New data shows that brain regions in infants just a few months old are specialized for faces, bodies, or scenes.

Within the visual cortex of the adult brain, as MIT neuroscientist Nancy Kanwisher discovered years ago, a small region is specialized to respond to faces, while nearby regions show strong preferences for bodies or for scenes such as landscapes. It’s long been thought that it takes years of visual experience for these areas to develop in children. However, a new MIT study suggests that it happens much earlier than previously believed.

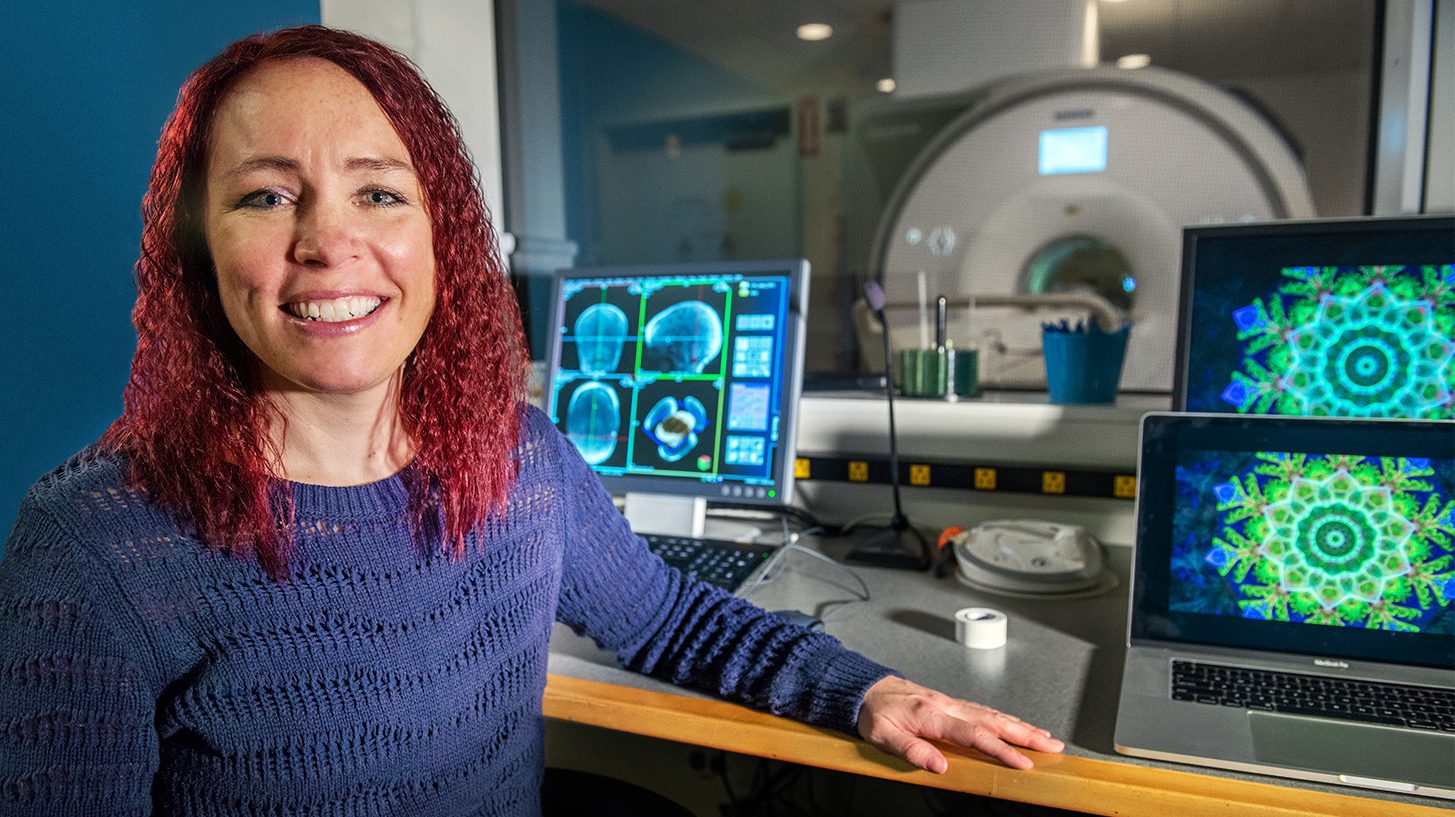

“These data push our picture of development, making babies’ brains look more similar to adults,” says Professor Rebecca Saxe, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research and the senior author of the study.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers collected usable data from more than 50 infants two to nine months old, a far greater number than any research lab has been able to scan before (indeed, there had been few studies of children younger than four or five years). This allowed them to examine the infant visual cortex in a way that had not been possible until now.

To get their data, they built a new type of fMRI head coil that is more comfortable for babies—who are notoriously hard to study in conventional MRI machines—and more powerful than the equipment they had previously developed especially to study infant brains.

After going into the scanner with a parent, the babies watched videos that showed either faces, body parts such as kicking feet or moving hands, objects such as toys, or natural scenes such as mountains. The results revealed that specific regions of the infant visual cortex show highly selective responses to these sights, in the same locations where those responses are seen in the adult brain. The selectivity for natural scenes, however, was not as strong as selectivity for faces or body parts.

The researchers now plan to take a closer look at the area of the brain that responds to scenes, this time using a noninvasive imaging technique that doesn’t require the participant to be inside a scanner. They also hope to perform new experiments examining other aspects of cognition, including how babies’ brains respond to language and music.

“The thing that is so exciting about these data is that they revolutionize the way we understand the infant brain,” says Heather Kosakowski, an MIT graduate student and lead author of the study. “A lot of theories have grown up in the field of visual neuroscience to accommodate the view that you need years of development for these specialized regions to emerge. And what we’re saying is actually, no, you only really need a couple of months.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.