A gene that keeps the brain sharp?

New findings may help explain why mental stimulation makes Alzheimer’s and age-related dementia less likely.

Researchers have long suspected that intellectual stimulation—from speaking multiple languages, reading, or doing word puzzles, for example—helps protect some people from developing dementia in old age, even if their brains show signs of neurodegeneration. Now an MIT team may have figured out why: such enrichment appears to activate a gene family called MEF2, which controls a genetic program in the brain that promotes resistance to cognitive decline.

By examining data on about 1,000 human subjects, the researchers found that cognitive resilience was highly correlated with expression of MEF2 and many of the genes that it regulates—many of which encode ion channels, which control how easily a neuron fires.

They also found that mice without the MEF2 gene in their frontal cortex did not show the expected cognitive benefit from being raised in a stimulating environment, and their neurons became abnormally excitable.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

The researchers then explored whether MEF2 could reverse some of the symptoms of cognitive impairment in a mouse model that expresses a version of a protein linked with dementia in the human brain. If these mice were engineered to overexpress MEF2 at a young age, they displayed neither the excessive neuronal excitability nor the cognitive impairments that the protein usually produces later in life.

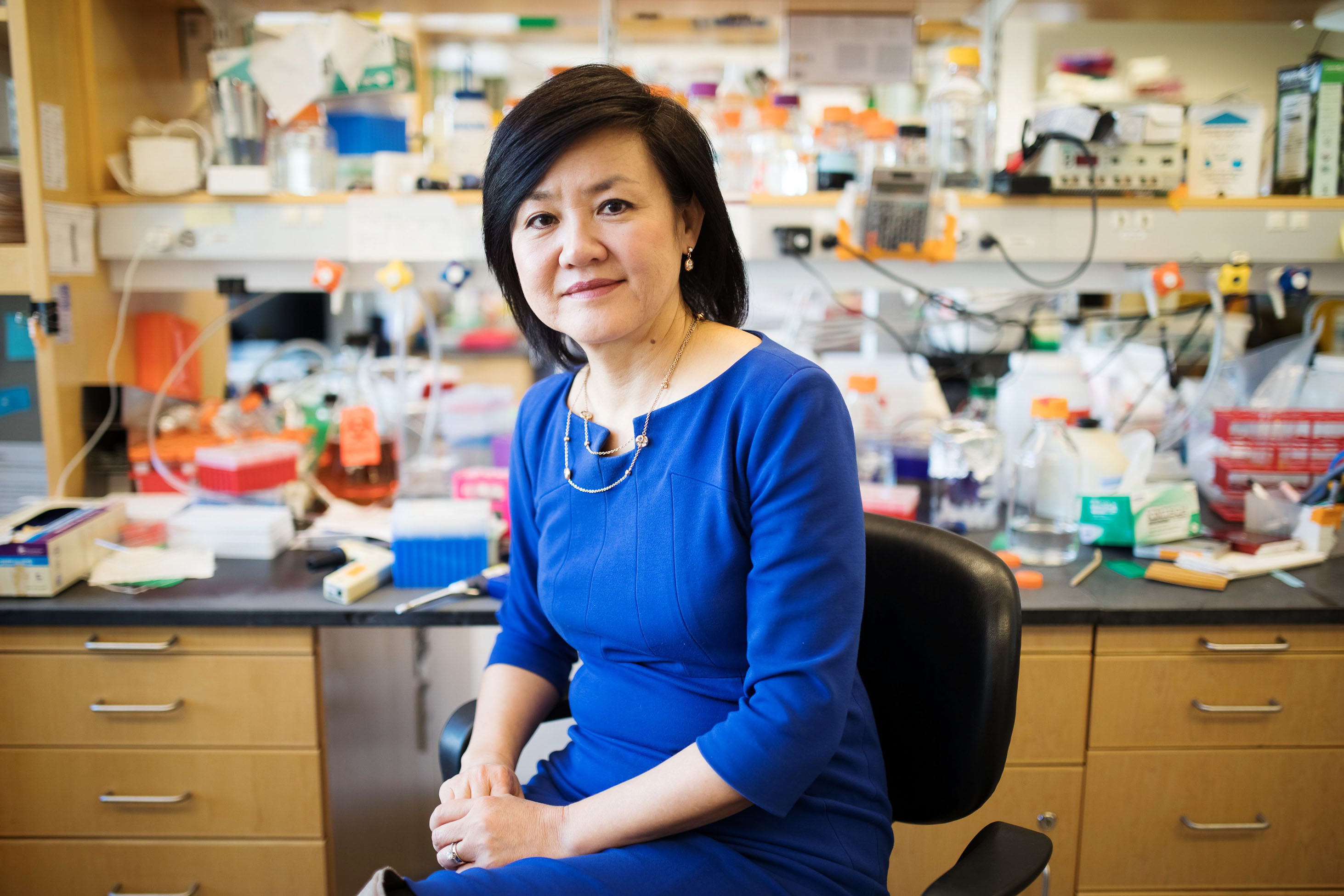

The findings suggest that enhancing the activity of MEF2 or its targets might help fend off age-related dementia. “It’s increasingly understood that there are resilience factors that can protect the function of the brain,” says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the senior author of the study. “Understanding this resilience mechanism could be helpful when we think about therapeutic interventions or prevention of cognitive decline.”