Walker and the “Indian Question”

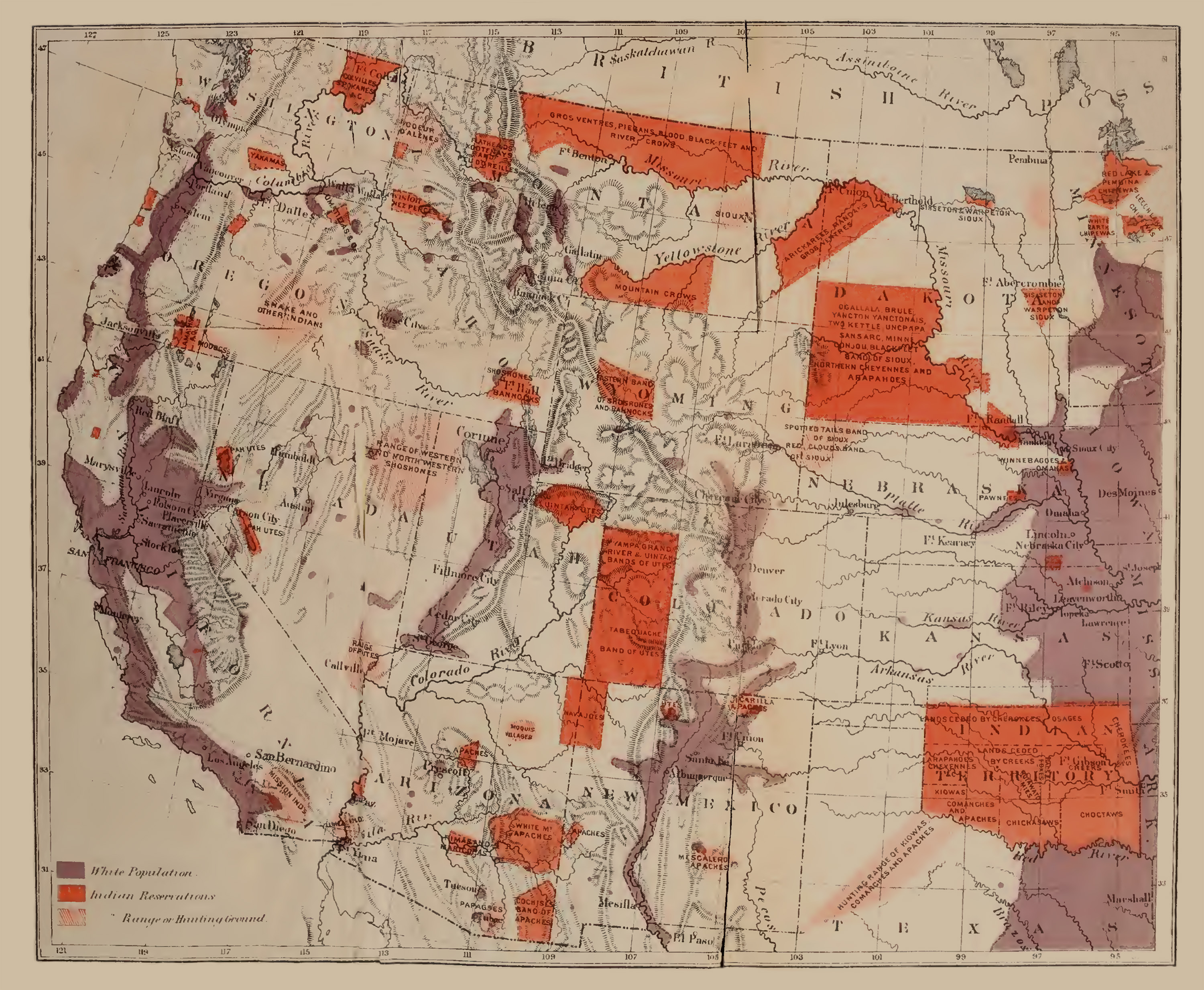

Before arriving at MIT, Francis Amasa Walker had twice led the US Census—and helped justify the troubling US policy of containing Native Americans on reservations.

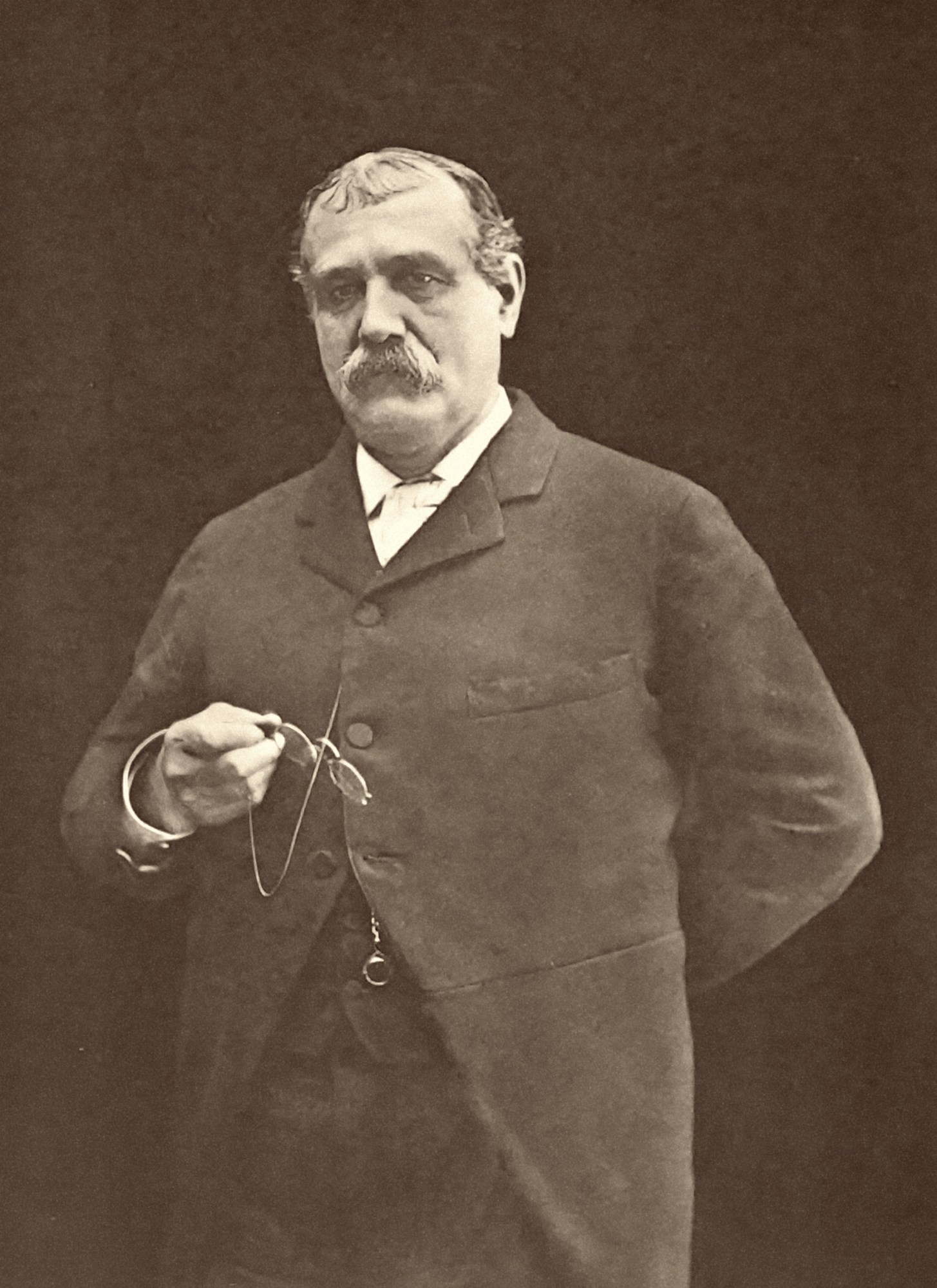

A decade before Francis Amasa Walker became MIT’s third president in 1881, he served as commissioner of Indian affairs for the United States. It was not a job for which he had any specific qualifications. Born to a prominent Boston family in 1840, Walker had served as a staff officer in the Civil War, taught political economy at Amherst College, been chief of the US Bureau of Statistics, and was appointed superintendent of the US Census of 1870, all before turning 30. Yet he had no experience with Native American issues. According to at least one historical account, President Ulysses S. Grant named him commissioner in part so he could continue to receive a federal paycheck at a time when the still-unfinished census had run out of money. A man of considerable energy, Walker divided his time between the two positions.

As commissioner, Walker applied his expertise in statistics and economics to mapping policy options in the midst of the Plains Wars, when Native Americans fought the US Army and settlers for control of land from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains—land that they had been promised under multiple treaties. The bureau’s annual report of 1872, which he wrote largely himself, attests that he conducted “hundreds of interviews … with men from every section of the country, of both [political] parties, and of all professions.” Yet he made just one trip to the Plains, where he met with the Sioux in Wyoming and Nebraska.

Walker’s landmark report was a comprehensive summary of issues involving the 300,000 Native Americans then living in the US (excluding those in Alaska, which had recently been purchased from Russia). According to his 1897 obituary in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, the report was “remarkable for its thorough review of the whole subject.” After leaving his post, Walker penned two articles on the topic, which he republished with material from the report in his 1874 book, The Indian Question.

Viewed from our contemporary vantage, two notable aspects of Walker’s writings are the unflinching way he blamed the conflict almost entirely on the aggression of whites and his description of the diversity among the tribes. Walker acknowledged that many of them had been uprooted from ancestral lands that were fertile and rich with game, then forced to live on land that could not support them and told to adopt European agriculture. Unable to feed themselves, they were dependent on rations promised under treaties with the US—rations that were frequently late or stolen. He also noted that the US had made nearly 400 treaties with the tribes—“confirmed by the Senate as are treaties with foreign powers”—but that many had been abrogated.

A potent source of conflict was illegal incursions by whites into Indian territory: “The eagerness of the average American citizen of the Territories for getting upon Indian lands amounts to a passion,” Walker wrote. “There is scarcely one of the ninety-two reservations at present established on which white men have not effected a lodgement: many swarm with squatters, who hold their place by intimidating the rightful owners.” In skirmishes between whites and Indians, Walker noted, whites “often commit atrocities rivaling those of the savages” and “are very often indiscriminate in their revenge, and do cruel injustice to peaceful bands.”

Walker also observed that conflicts had escalated with the 1869 completion of the Trans-Continental Railroad—and would likely grow with anticipated future railroads, which would cut right through reservations that had been promised to the Indians.

Walker's "Indian Question" had two parts: “What shall be done with the Indian as an obstacle to the national progress?” and “What shall be done with him when, and so far as, he ceases to oppose or obstruct the extensions of railways and settlements?”

Despite this frank and largely accurate assessment, today Walker’s book is regarded by many as a racist screed, and he is seen as a proponent of “scientific racism”—a discredited movement that misused the tools of science to argue for the inherent superiority of whites. Indeed, Walker wrote that the US government was justified in pushing Native Americans off their ancestral lands so they could be used more productively by “civilized” whites.

The “Indian Question” he posed had two parts: “What shall be done with the Indian as an obstacle to the national progress?” and “What shall be done with him when, and so far as, he ceases to oppose or obstruct the extensions of railways and settlements?”

Walker believed that the choice was “between two antagonistic schemes—seclusion and citizenship.” He favored the former because, he wrote, “the principle of secluding Indians from whites for the good of both races is established by an overwhelming preponderance of authority.” He advocated confining Indians to reservations and forcing them to farm or otherwise work until they were assimilated into the US economy. Meanwhile, he maintained, the US should make good on its treaty obligations because doing so would be cheaper than further military action: “Expensive as is the Indian service as at present conducted in the interest of peace, it costs far less than fighting.”

His arguments may have helped cement the system of Indian reservations, but Walker did not create it: the first reservation was established in southern New Jersey in 1758. The modern system started in the 1810s, after Andrew Jackson defeated the Creek Confederation at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and negotiated the “removal” of several Eastern tribes to west of the Mississippi River.

Jackson became president in 1829; the following year he signed the Indian Removal Act, which led directly to what’s known as the Trail of Tears, when 125,000 Native Americans from Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Florida were forced to walk hundreds of miles to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi. All this happened before Walker was born.

While Walker served in the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War, the US was simultaneously fighting multiple wars with various tribes on the Plains. These wars were frequently accompanied by massacres of Native American women and children. In 1867 Congress created a “peace commission” to resolve the many outstanding issues.

Grant ran for president in 1868 with a plan for improving relations between the US and the Indian nations. Forty days after taking office, he appointed Ely S. Parker, a Towanda Seneca also known as Donehogawa, as the first Native American commissioner of Indian affairs. Parker, an engineer who had graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic, had served with Grant in the Civil War as a commissioned lieutenant colonel, and transcribed the terms of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in part because of his excellent handwriting.

Parker had enemies. In December 1870, the racist former chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners wrote a letter to Congress accusing him of corruption. Parker eventually cleared his name after a months-long investigation, but he was devastated by the ordeal and resigned. Walker was his replacement, charged with continuing the administration’s policy of making good on treaty commitments and rooting out corruption.

Following a wave of violence against Indians in the Oregon Territory, Walker resigned in December 1872, having served barely a year. He joined the faculty at Yale, where he taught political economy and wrote The Indian Question, which expanded on his factual report with analysis and policy recommendations. The book soon “became a standard treatise,” according to a 2018 biography published by the American Statistical Association.

Today Walker’s writings cast a shadow over MIT’s Native American community. “From my understanding, when he wrote that book, Indigenous people were [caught in a] very unusual dichotomy: We were considered by non-Indigenous as both mystical in a Last of the Mohicans sense—noble, willing to make sacrifices, warriors—while simultaneously we were considered savages and childlike,” says Alvin Harvey, SM ’20, a member of the Navajo Nation, a PhD student in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and president of the MIT Native American Student Association.

When Harvey read Walker’s book, he says, he was “shocked to find MIT’s history with Indigenous people extended that far back—that one of its presidents was influential in the system that still exists to this day.”

“I don’t think that [Walker] was without compassion for people, but he was an essentialist,” says Deborah Douglas, the MIT Museum’s director of collections, who is developing an exhibit about the history of race at MIT.

Walker believed there were “essential differences between races, between men and women,” explains Douglas. That belief is on full display in his book, in which he wrote that colonizers “beat the savages with their own weapons, as men of the higher race will always do when forced by circumstances to such a contest.” But despite his views, he appeared willing to recognize exceptional individuals, regardless of their heritage or sex: Robert Taylor, MIT’s first Black graduate, entered MIT on Walker’s watch in 1888, and Walker approved the creation of the Margaret Cheney Room, a community center for MIT women, in 1884.

“Having Walker as the third president of MIT—it doesn’t make MIT an inherently bad institution. I think that MIT has done so many amazing things for the world,” says Luke Bastian ’21, also a member of the Navajo Nation. Nevertheless, he says, it took extensive negotiations last year for Native American students to get their own physical space on campus. “We’re here. We exist,” Bastian says. That’s “the basic thing” that the group struggled to get MIT to acknowledge.

Harvey, Bastian, and other members of the MIT Native American community also successfully persuaded MIT to post a statement on its website acknowledging that MIT is built on “unceded territory of the Wampanoag Nation.”

“We acknowledge the painful history of genocide and forced occupation of their territory,” the statement goes on to say, “and we honor and respect the many diverse Indigenous people connected to this land on which we gather from time immemorial.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.