The $1 billion Russian cyber company that the US says hacks for Moscow

Washington has sanctioned Russian cybersecurity firm Positive Technologies. US intelligence reports claim it provides hacking tools and runs operations for the Kremlin.

- Biden administration sanctions six Russian companies over cyber activities

- List includes well-known Moscow security firm Positive Technologies

- US officials privately believe Positive provides hacking tools and support to Russian intelligence

The hackers at Positive Technologies are undeniably good at what they do. The Russian cybersecurity firm regularly publishes highly-regarded research, looks at cutting edge computer security flaws, and has spotted vulnerabilities in networking equipment, telephone signals, and electric car technology.

But American intelligence agencies have concluded that this $1 billion company—which is headquartered in Moscow, but has offices around the world— does much more than that.

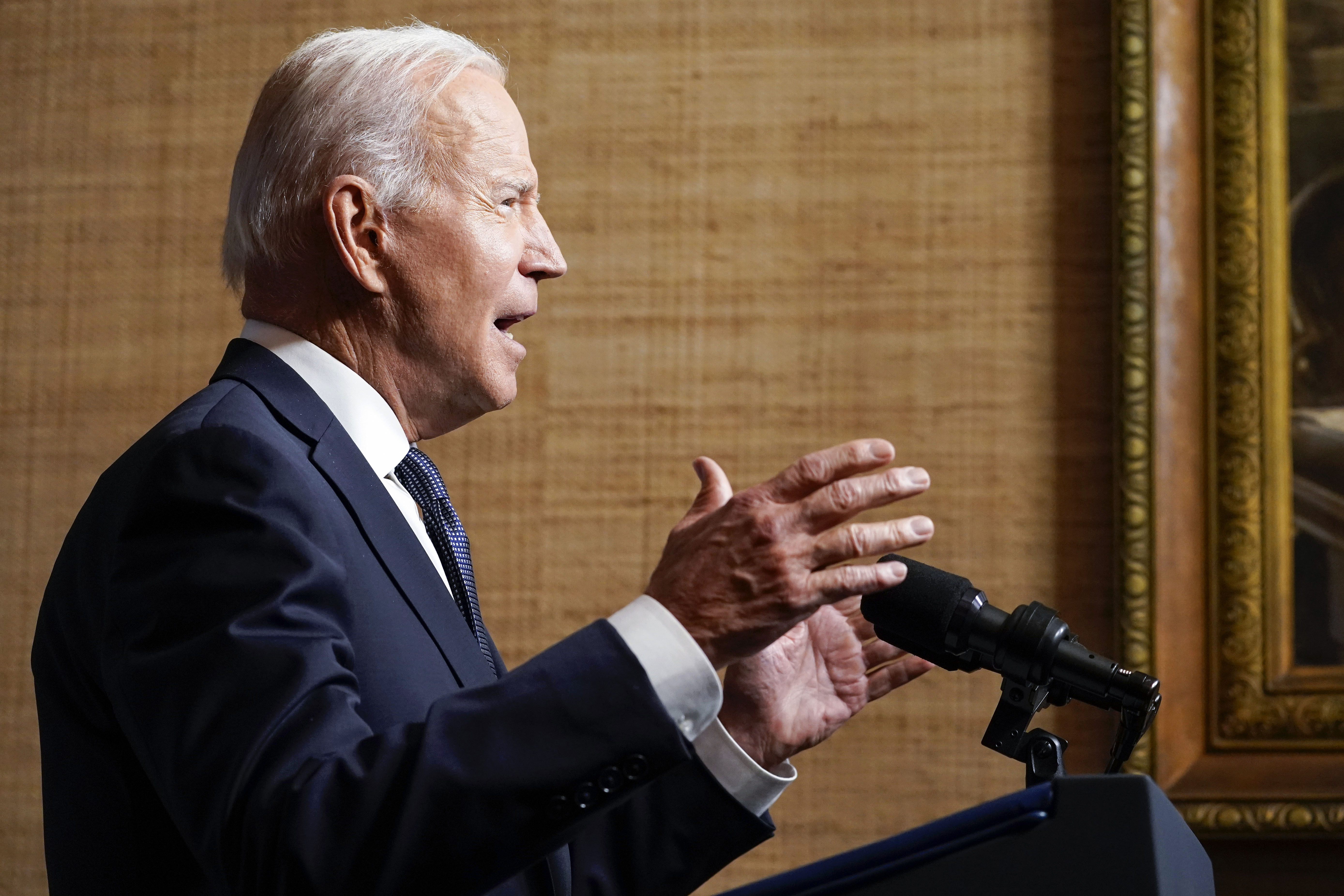

Positive was one of a number of technology businesses sanctioned by the US on Thursday for its role in supporting Russian intelligence agencies. President Joe Biden declared a national emergency to deal with the threat he says Moscow poses to the United States. But the details of the sanctions released by the Treasury Department only cover a small fraction of what the Americans now believe about Positive’s role in Russia.

MIT Technology Review understands that US officials have privately concluded that the company is a major provider of offensive hacking tools, knowledge, and even operations to Russian spies. Positive is believed to be part of a constellation of private sector firms and cybercriminal groups that support Russia’s geopolitical goals, and which the US increasingly views as a direct threat.

The public side of Positive is like many cybersecurity companies: staff look at high-tech security, publish research on new threats, and even have cutesy office signs that read “stay positive!” hanging above their desks. The company is open about some of its links to the Russian government, and boasts an 18-year track record of defensive cybersecurity expertise including a two-decade relationship with the Russian Ministry of Defense. But according to previously unreported US intelligence assessments, it also develops and sells weaponized software exploits to the Russian government.

One area that’s stood out is the firm’s work on SS7, a technology that’s critical to global telephone networks. In a public demonstration for Forbes, Positive showed how it can bypass encryption by exploiting weaknesses in SS7. Privately, the US has concluded that Positive did not just discover and publicize flaws in the system, but also developed offensive hacking capabilities to exploit security holes that were then used by Russian intelligence in cyber campaigns.

Much of what Positive does for the Russian government’s hacking operations is similar to what American security contractors do for United States agencies. But there are major differences. One former American intelligence official, who requested anonymity because they are not authorized to discuss classified material, described the relationship between companies like Positive and their Russian intelligence counterparts as “complex” and even “abusive.” The pay is relatively low, the demands are one-sided, the power dynamic is skewed, and the implicit threat for non-cooperation can loom large.

Tight working relationship

American intelligence agencies have long concluded that Positive also runs actual hacking operations itself, with a large team allowed to run its own cyber campaigns as long as they are in Russia’s national interest. Such practices are illegal in the western world: American private military contractors are under direct and daily management of the agency they’re working for during cyber contracts.

US intelligence has concluded that Positive did not just discover and publicize flaws, but also developed offensive hacking capabilities to exploit security holes that it found

Former US officials say there is a tight working relationship with the Russian intelligence agency FSB that includes exploit discovery, malware development, and even reverse engineering of cyber capabilities used by Western nations like the United States against Russia itself.

The company’s marquee annual event, Positive Hack Days, was described in recent US sanctions as “recruiting events for the FSB and GRU.” The event has long been famous for being frequented by Russian agents.

NSA director of cybersecurity Rob Joyce said the companies being sanctioned "provide a range of services to the SVR, from providing the expertise to developing tools, supplying infrastructure and even, sometimes, operationally supporting activities,” Politico reported.

One day after the sanctions announcement, Positive issued a statement denying “the groundless accusations” from the US. It pointed out that there is “no evidence” of wrongdoing and said it provides all vulnerabilities to software vendors “without exception.”

Tit for tat

Thursday’s announcement is not the first time that Russian security companies have come under scrutiny.

The biggest Russian cybersecurity company, Kaspersky, has been under fire for years over its relationships with the Russian government—eventually being banned from US government networks. Kaspersky has always denied a special relationship with the Russian government.

But one factor that sets Kaspersky apart from Positive, at least in the eyes of American intelligence officials, is that Kaspersky sells antivirus software to western companies and governments. There are few better intelligence collection tools than an antivirus, software which is purposely designed to see everything happening on a computer, and can even take control of the machines it occupies. US officials believe Russian hackers have used Kaspersky software to spy on Americans, but Positive—a smaller company selling different products and services—has no equivalent.

Recent sanctions are the latest step in a tit for tat between Moscow and Washington over escalating cyber operations, including the Russian-sponsored SolarWinds attack against the US, which led to nine federal agencies being hacked over a long period of time. Earlier this year, the acting head of the US cybersecurity agency said recovering from that attack could take the US at least 18 months.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.