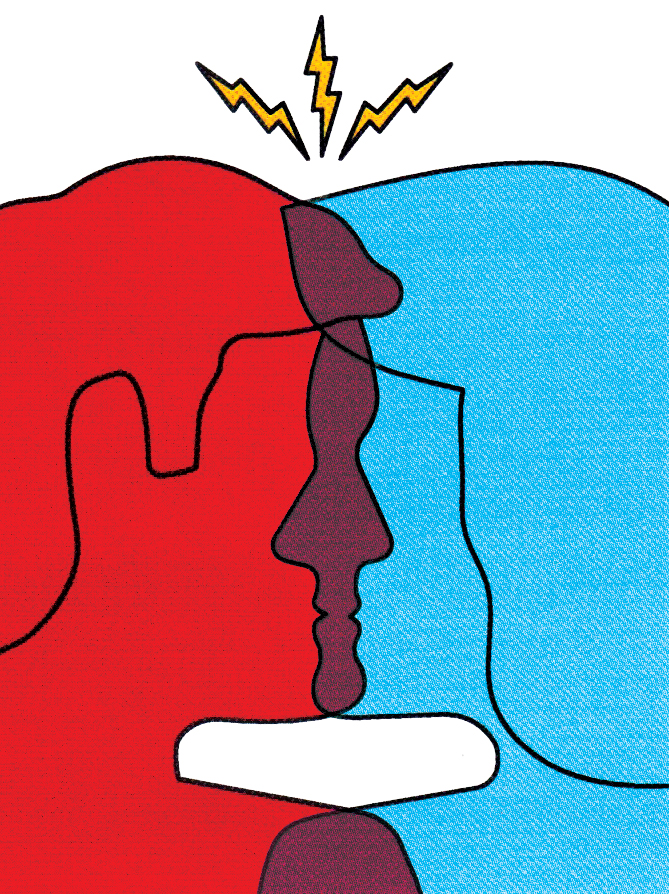

Contact tracing without Big Brother

Contact tracing—notifying people who might have been exposed to disease—will be key to controlling the covid-19 pandemic until a vaccine is available, but the tactic raises obvious privacy concerns. Now a team led by MIT researchers and including experts from many institutions is developing a system called Private Automatic Contact Tracing (PACT) that augments the efforts of public health officials without compromising privacy.

The system relies on short-range Bluetooth signals emitted by people’s smartphones. These signals represent random strings of numbers, likened to “chirps” that other nearby phones can remember hearing. Institute Professor Ron Rivest and Daniel Weitzner, a principal research scientist in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), are principal investigators on the project.

People who test positive for covid-19 can upload the list of chirps their phone has put out in the past 14 days to a database. Other people can then scan the database to see if any of those chirps match the ones picked up by their phones. If there’s a match, a notification will inform those who may have been exposed to the virus, giving them advice from public health authorities on next steps to take. But none of the chirps will be traceable to a specific person. “We’re not tracking location, not using GPS, not attaching your personal ID or phone number to any of these random numbers your phone is emitting,” Weitzner says.

This approach to contact tracing benefited from the early work of Safe Paths, a citizen-centric, open-source set of digital tools and platforms being developed in a cross-MIT effort led by Media Lab associate professor Ramesh Raskar with input from many other organizations and companies.

The Safe Paths platform, currently in beta, comprises both a smartphone application, PrivateKit, and a web application, Safe Places. The PrivateKit app will enable users to match the personal diary of location data on their smartphone with the anonymized, redacted, and blurred location history of infected patients. The PACT Bluetooth protocol will also be available through Safe Paths.

Maintaining privacy has been a guiding principle for the project. “User location and contact history should never leave a user’s phone without direct consent,” Raskar says. “We strongly believe that all users should be in control of their own data, and that we should never need to sacrifice consent for covid-19 safety.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.