Facebook at a Crossroads

Mark Zuckerberg built himself a nice ad business—but he wants it to be so much more.

More than half of the 3.4 billion people with Internet access log on to Facebook each month. Revenue in the first nine months of 2016 jumped 36 percent to $19 billion; profit nearly tripled, to $6 billion. Yet the company’s founder has spent the year talking up his plans to become something much larger and more meaningful.

At an event in April promoting his plans for Facebook’s next 10 years, Zuckerberg said the company would develop new drone, wireless, and satellite technology to provide Internet connectivity to everyone on Earth. And he talked up how his Oculus virtual reality division, acquired in 2014 at a cost of $2 billion, would revolutionize the way people work and socialize.

Progress on those big dreams has been slight, with setbacks.

Facebook did launch a prototype of its Internet drone (although it crashed on landing), and showed off prototypes of new wireless technologies. But the first phase of Zuckerberg’s Internet connectivity plans suffered an embarrassing defeat. India’s telecom regulator banned the company’s “Free Basics” scheme that made certain online services free to access, saying it distorted the market.

Meanwhile, the Oculus Rift virtual-reality headset launched to generally good reviews (including from MIT Technology Review). But at a price of $600, not including the PC needed to power the device, the Rift appears destined to remain a niche gaming accessory for some time. In December, Facebook split the Oculus division in two, demoting its CEO and creating groups to work separately on high-end headsets and more limited, mobile virtual-reality experiences.

Altogether, Zuckerberg has yet to prove that he can build a new business or product to stand alongside his existing one: offering communications tools that target ads to their users. And recent months have shown that he can’t simply take that core business for granted while he boots up longer-term ideas. Facebook’s chief financial officer recently cautioned investors that revenue growth will slow in 2017 because the service can’t cram more ads in front of people without annoying them.

The company is pushing its users and content creators to embrace live, mobile video, which could eventually be a lucrative vehicle for ads (although Facebook admitted this year that it had overstated by 60 to 80 percent how much time people spent watching videos.) And it can do more with Instagram. But expanding into new markets isn’t easy. The company’s reach is already huge—1.2 billion people look at the News Feed’s filtered version of reality each day. That scale and the company’s model of finely targeting ads using personal data generate a steady supply of suspicion and controversy.

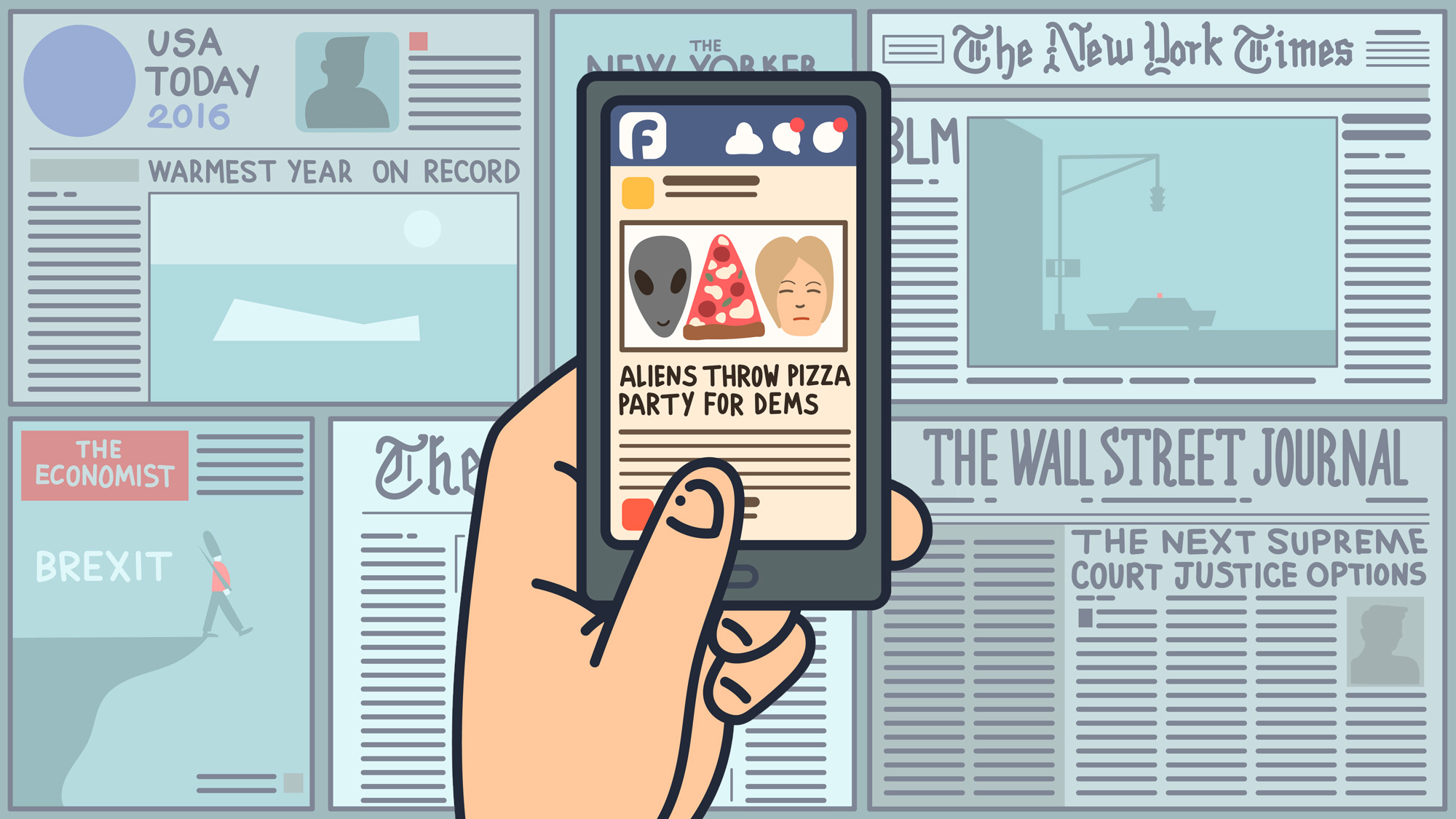

Facebook’s new live video feature has led to tricky questions about its duty to the public. This summer, the company initially blocked a stream of the last moments of Philando Castile after he was shot by police in Minnesota. A ProPublica investigation in October showed that the company was probably breaching federal laws banning companies from targeting housing and employment ads on the basis of race. It recently had to take action to suppress the spread of false information after questioning of the social network’s role in the presidential election.

In a video this week in which he reflected on 2016, Zuckerberg seemed to acknowledge for the first time that Facebook has similar responsibilities to a traditional media company. Such talk may pacify some critics but also motivate others by making it seem fair to hold the company responsible for how information spread on its platforms affects the world.

Concerns about Facebook’s power don’t seem to have scared off advertisers, but they will surely dog any future moves to expand its businesses. (The company’s plans to launch in China will be particularly fraught; see “Mark Zuckerberg’s Long March to China.”)

In 2017, Zuckerberg will have to manage the awkward adolescence of his existing business and try to show real progress on his aspirations for one day doing something larger.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.