The Recipe for the Perfect Robot Surgeon

Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci robot is a technical marvel. Nearly half a million operations were performed in the U.S. by surgeons controlling its large, precise arms last year. One in four U.S. hospitals has one or more of the machines, which perform the majority of robotic surgeries worldwide and are credited with making minimally invasive surgery commonplace.

But when executives from Verb Surgical, a secretive joint venture between Alphabet and Johnson & Johnson, presented at the robotics industry conference RoboBusiness late last month, they made the da Vinci sound lame.

Intuitive’s machine, with an average selling price of $1.54 million, is too expensive and bulky, they grumbled. Pablo Garcia Kilroy, Verb’s vice president of research and technology, complained that while da Vinci is an impressive tool, it’s a dumb one that hasn’t widely transformed surgery. He said that while it enables surgeons to perform very delicate movements, it doesn’t assist with the cognitive skills that set the best surgeons apart.

“Surgery is more than just hand-eye coördination,” said Garcia. “It’s about how well you perceive anatomy—tumors, nerves, and vessels—and your strategy [during an operation].” When asked to comment on Verb's observations about its technology, Intuitive's VP of global public affairs, Paige Bischoff, said that "many" of the 3.5 million da Vinci procedures to date were for cancer or complex surgeries.

Verb claims to be developing a product that will make robotic surgery much more powerful and widely used than the da Vinci has. Garcia didn’t describe that product, and the company has said that a working prototype to be completed this year won’t be publicly unveiled. But Garcia laid out the key features Verb thinks a next-generation robotic surgeon needs. Patents that list him as a co-inventor offer further clues.

One of Verb’s priorities is to use artificial intelligence to help surgeons interpret what they see inside a patient. Existing robots just leave surgeons to look at a video feed. Garcia said that artificial neural networks like those Google uses for image search could annotate a feed with anatomical data and guidance such as information about the boundaries of a tumor. That could give any surgeon a level of expertise usually obtainable only after experience with thousands of cases.

Verb has said its robot will be significantly cheaper than a da Vinci. Garcia said that he also wants to make it much smaller, and that connecting surgical robots over the Internet would make it possible to quickly improve their skills and the guidance they can offer surgeons.

Google researchers recently got robotics software to learn complex skills more quickly by having multiple robot arms share their experiences (see “Google Builds a Robotic Hive-Mind Kindergarten”). “We see a similar dynamic happening in surgery,” said Garcia.

Verb’s robotics technology has been in development for almost four years, though the company only incorporated in August 2015. The joint venture was created by combining a project from Verily, previously known as Google Life Sciences, and Ethicon, a medical-device company owned by Johnson & Johnson. Ethicon had been working on surgical robotics with nonprofit research lab SRI International, and Verb licensed that technology.

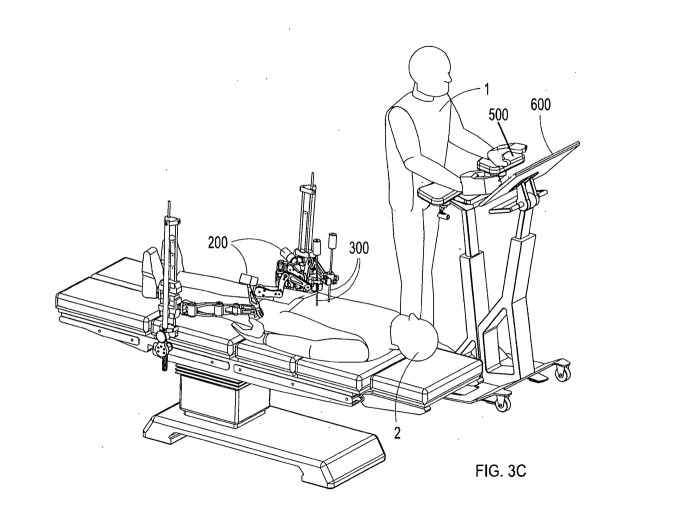

Some Verb employees, including Garcia and the company’s director of research, Karen Shakespear Koenig, previously worked at SRI. The pair are among the authors on patents originating in 2013 that describe a “hyperdexterous surgical system” and a “compact robotic wrist.”

The documents detail systems with more mobile joints than surgical robots on the market, saying that would allow for smaller, more capable robots. They claim this would avoid one problem with existing robots: they can’t reach certain “dead zones” in a patient, because their bulky arms limit maneuverability. SRI declined to elaborate what technologies it has licensed to Verb.

Umamaheswar Duvvuri, an assistant professor and director of robotic surgery for head and neck surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, says that Verb has correctly identified a major opportunity both to build a business and to improve health care.

The da Vinci is almost exclusively used for just a handful of common, relatively simple procedures, such as prostate surgery and hysterectomies, he says. Some studies have found that the robot doesn’t significantly improve patient outcomes or costs. The nonprofit ECRI Institute describes clinical evidence on the quality of outcomes as “low to moderate.”

Robotic systems that augment a surgeon’s thinking as well as motor control have a better prospect of being used for a wider range of operations and improving the results, says Duvvuri. “This is the kind of approach we need if we are to figure out how to make a good surgeon into a great surgeon and provide better care for the patient,” he says.

Garcia of Verb also envisions being able to significantly increase the productivity of surgery by making surgical robots with a degree of automation. One surgeon might be able to supervise multiple theaters, staffed by robots and less-skilled personnel, he said.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.