Election Tech Roundup: Is 2016 the Year of Psychological Profiling?

The 2008 presidential election heralded wide use of online social media. Four years later saw the emergence of data-driven campaigning, with President Obama’s team doing a particularly good job of testing and implementing tailored messages to tiny slivers of the electorate.

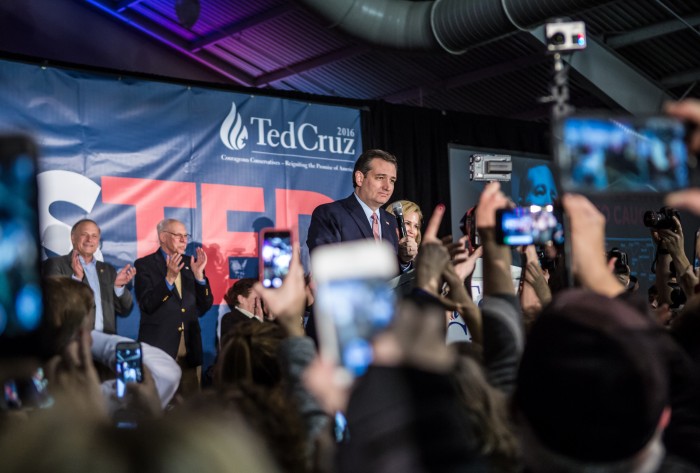

Will 2016 be the year of psychological profiling? Ted Cruz, winner of yesterday’s Iowa Republican caucuses, relied heavily on a company called Cambridge Analytica, which dishes up data-driven tools with the added twist of “psychographic profiling.” It uses survey data to attempt to classify voters by personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Then it then tailors e-mail and door-knock messages in ways thought to appeal to these traits. Cruz bet heavily on the company, spending $750,000 through the October reporting cycle.

But at the same time, the Cruz victory might have been more about Donald Trump falling short on the old-fashioned ground game: he had relatively few people knocking on doors and making sure supporters got out to vote.

On the Democratic side, Clinton had both a strong ground game and all the data-driven tools, including some from a startup partly funded by Eric Schmidt called the Groundwork, which employs former Obama campaign strategists.

However, the Clinton technology war chest wasn’t enough to decisively turn back the campaign of Bernie Sanders; the matchup ended in a virtual tie, with Clinton taking 49.9 percent of the vote to Sanders’s 49.6 percent.

On caucus night itself, technology helped streamline the traditionally messy process in Iowa. In 2012, Mitt Romney was erroneously announced as the winner, when in fact Rick Santorum had won. To prevent that from happening again, both parties used a caucus-reporting app unveiled by Microsoft in June.

The main job of the app was to ensure that only authorized precinct captains would report results—and, on the Democratic side, to calculate whether any given caucus had enough members to be viable. Precinct captains were instructed to enter the number of caucus participants and how many voted for each candidate. The company said the system worked as planned, but there were scattered reports that the app was seizing up, probably because of unexpectedly high traffic. (The Sanders campaign also built its own app that helped these same captains keep track of how preferences changed during the course of the night.)

There were still some low-tech counting methods used. In six cases, deadlocked caucus sites settled who would get how many delegates with a coin toss, as allowed under the state’s rules. Clinton won all six of these tosses—a one in 64 probability—but this lucky streak had a negligible effect on the outcome. Overall, the process was still so murky that the Sanders campaign has said it is assessing whether to seek a recount.

However the election turns out, we can all count on tech titans to play powerful behind-the-scenes roles to make sure the next president is friendly to the industry.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.