The Emerging Science of Urban Skylines

In New York, about two-thirds of the city’s energy use goes to cooling, heating, and lighting buildings. It’s similar in other North American cities.

The shapes of these buildings largely determine how this energy radiates into the environment. In other words, a city’s skyline is an important factor in its carbon footprint.

That raises an interesting set of questions. How do building shapes vary from one city to the next, in particular with city size? And could this lead to a more general understanding of how energy consumption changes as cities grow or shrink?

Today, we get an answer thanks to the work of Markus Schlapfer at the Santa Fe Institute and pals, who have analyzed the shape of almost five million buildings in cities of various sizes across North America. These guys say there is a simple relationship between average building height and city size and that this has important implications for the way cities consume energy.

This kind of work has become possible because urban scientists are able to measure the size of buildings relatively easily using techniques such as laser ranging. This data is increasingly being placed in the public domain by the cities themselves or by open source projects such as OpenStreetMap.

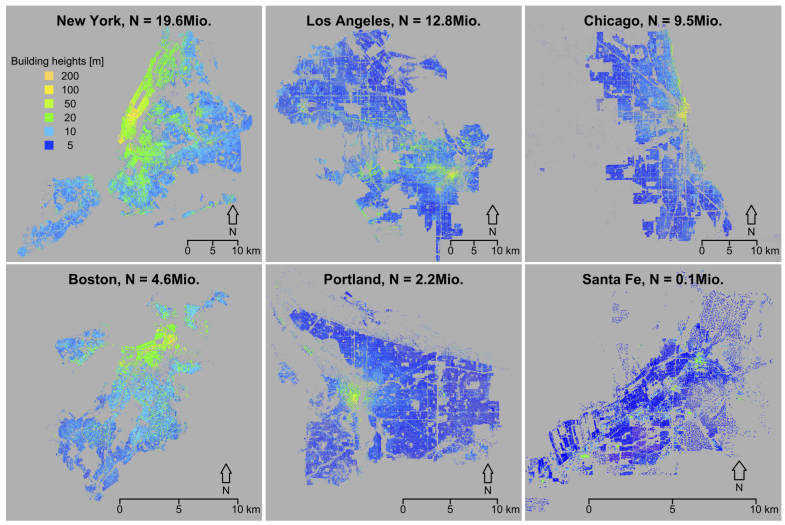

Schlapfer and co simply downloaded this information from around five million buildings from 12 North American cities. These ranged from the largest, New York and Los Angeles (with populations of 20 million and 13 million respectively), to midsized cities such as San Francisco and Austin (with populations of four million and two million respectively) to small cities such as Ann Arbor and Santa Fe (with populations of 300,000 and 100,000 respectively).

The size distribution shows a clear pattern. Schlapfer and co say that at first glance the data matches the general expectation that the average height of buildings increases with city size and that within a city, buildings get taller nearer the center.

But a closer look at the data reveal some more detailed patterns. For a start, at the center of cities, average building size increases with population over two orders of magnitude. And this reflects a change in the shape of buildings from larger, flatter structures in smaller cities to taller, narrower ones in bigger cities.

The reason for this trend is straightforward to model. As the population of a city increases, land becomes more expensive. Indeed, land price increases more quickly than personal income. So the only way to make it affordable is to reduce the amount of space people use, a trend that eventually results in slums, or to increase the volumes of buildings by making them taller.

Since land is more expensive in city centers, buildings should be taller there, too.

In theory, this trend should be good for energy efficiency. Taller buildings become more like cubes and so generally have a smaller ratio of surface area to volume. This helps make buildings more energy efficient. “We see that building sizes do increase with city size, creating the conditions for greater energy efficiency in terms of climate control,” say Schlapfer and co.

Up to a point. In cities such as New York and Boston this trend has led to the construction of much taller skyscrapers in which are less energy efficient. “The surface-to-volume ratio increases again in the downtown cores of large cities, due to the proliferation of tall, needle-like buildings,” they say.

However, there is a practical limit to the height of buildings which is imposed by the volume of building that must be devoted to lifts, stairwells, and so on. “Many architects see it as a rule of thumb that with present technology a building taller than about 100 stories is not economically viable,” say the team.

They conclude that on average, the shapes of buildings in North American cities converge on a cube-like shape as cities get bigger—that’s the most energy efficient shape.

That should have important implications for energy use in future megacities. All over the world, populations are converging on cities at a rate that is driving the greatest and most rapid period of city building in history.

City planners expect the urban fabric in developing cities to exceed all that has been built so far. China, for example, poured more concrete between 2011 and 2013 than the U.S. used in the entire 20th century.

That will have significant consequences since the energy used in these cities will inevitably increase.

The new science of skylines should help urban scientists to understand the processes involved. But to what extent they can help mitigate the consequences for the environment is less clear.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1512.00946 : Urban Skylines: Building Heights And Shapes As Measures Of City Size

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.