Researchers Take a Step Toward Vocal Cord Transplants

People burdened by severely damaged vocal cords have new reason to hope they could someday get their voices back. Tissue engineers have for the first time made structures that not only resemble real vocal cords but also function like them.

Impaired vocal cords make it hard or impossible for people to speak. There is currently no way to fix severe damage, which can result from surgery, traumatic injury, or diseases like cancer. So researchers at the University of Wisconsin are trying to engineer replacements.

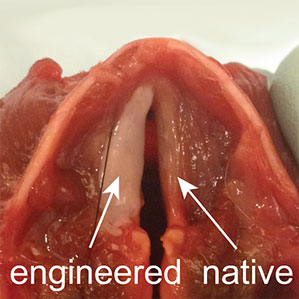

The researchers implanted the engineered tissue into a larynx that had been taken from a dog and had one of its vocal cords removed. They demonstrated that the lab-made tissue vibrates and sounds like healthy tissue. (Click on the video below to hear the sound the tissue makes when researchers push air through the larynx.) Further tests in mice showed that the tissue elicited a minimal immune response, raising the researchers’ hopes that such implants could eventually work in people.

Vocal cords are bands of tissue stretched horizontally on either side of the larynx, or voice box, just above the trachea, or windpipe. They open during breathing and vibrate when a person is using his or her voice. Restoring the voice of someone with a badly damaged vocal cord is challenging because the tissue must thrive under unique biomechanical conditions. Its precise structure and makeup is what makes it able to withstand frequent stress, strain, and vibration.

In recent years researchers have tried to re-create that structure in the lab, using polymer scaffolds to culture and grow stem cells in three dimensions—a well-established tissue engineering approach. But while they’ve made tissues that look the part, the engineered tissue has not vibrated effectively, says Nathan Welham, an associate professor of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Those previous attempts may have been limited because they didn’t use cells from vocal cord tissue. But Welham, who says that real vocal cord cells “may hold some of the keys to unlocking” the problem, and his colleagues got such cells from human cadavers and from donors who had healthy tissue removed during surgery. They used a collagen scaffold to culture and grow the cells, and after a couple of weeks they had what resembled vocal cords. Subsequent protein analysis confirmed that it contained a large portion of the specific kinds of proteins found in the real tissue.

It will take at least several more years of development and testing before this process might be used in vocal cord transplants on people. But if further studies confirm the observation that tissue engineered from the cells of unrelated donors doesn’t cause a harmful immune response, it should be possible to generate a large amount of vocal cord tissue from a small number of sources.

Welham says it’s too early to tell whether an engineered vocal cord might change the sound of a person’s voice, but he adds that it probably wouldn’t. The uniqueness of your voice has more to do with the shapes of your throat, nose, and mouth.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.