Why Environmentalists Aren’t Winning the War with Natural Gas

Environmental groups won a major victory in California in late June when the group proposing a 600-megawatt natural-gas-fired power plant near Avenal said it would abandon the project. Slated to cost nearly $2 billion, the Avenal plant was the subject of a dozen years of controversy and legal wrangling, and last year a federal appeals court vacated environmental approvals for the project.

For the Sierra Club and other groups attempting to block all new fossil-fuel plants in the United States, the decision to abandon Avenal came as a signal: the tactics that have worked against the coal industry, which has not won approval for a new plant in more than a year, can now be applied successfully to the expanding natural-gas industry.

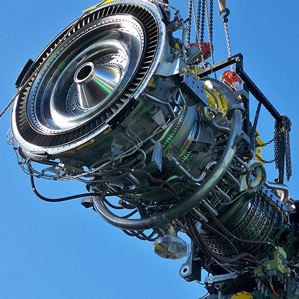

But such victories are not the rule. About 275 miles south of Avenal down Interstate 5, in Carlsbad, an equally ambitious natural-gas plant won approval from the state’s Public Utilities Commission in May. The Carlsbad Energy Center, a 500-megawatt, five-unit plant, is designed to replace generation capacity lost with the closure of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in 2013 and the impending retirement of the Encina Generating Station, also in Carlsbad.

In many cases, such plants are cheaper to build, and more economical over the long term, than competing forms of power generation. According to the Energy Information Administration, the cost of energy over their lifetime is $75.20 per megawatt-hour for conventional natural-gas plants that will come online in 2020. For conventional coal plants it’s $95.10, and for solar it’s $125.30. Only onshore wind, at $73.60, is less costly than natural gas.

According to data from the Energy Information Administration, more than 25,000 megawatts of natural-gas generation capacity—more than 50 Carlsbad-sized plants, enough to serve millions of homes and businesses—has been added to the nation’s fleet since 2010, including nearly 7,000 megawatts since January 2014. Thanks to cheap, abundant domestically produced supplies, another 53,000 megawatts of capacity is expected to come online from 2015 to 2020.

Meanwhile, more than 25,000 megawatts of coal plant capacity will be retired between 2015 and 2023, according to the EIA. Natural gas now accounts for 27 percent of U.S. power generation, while coal accounts for 39 percent and renewables, including wind and solar, account for 13 percent.

Utility executives argue that natural-gas plants are in fact critical to integrating more renewables into the grid. Many of the planned facilities, like the Carlsbad Energy Center, are fast-starting gas-fired turbines that can ramp up to near-full capacity within minutes rather than hours. Designed as “peaker” plants, they run on demand to fill in gaps in the power supply, which are often caused by the intermittency of renewable sources such as wind and solar.

According to the EIA, increased use of natural gas is one reason overall greenhouse-gas emissions in the United States were 212 million metric tons lower in 2013 than in 2005 (see “King Natural Gas”). Fuel-switching from coal and oil accounted for nearly one-third of those reductions. Natural gas, when burned, emits about 51 percent as much carbon dioxide as coal; on that basis, if all 25,000 megawatts of the coal slated for retirement over the next eight years were to be replaced by natural gas, about 82 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions a year would theoretically be avoided.

In the real world, of course, things aren’t that neat: opponents point out that life-cycle emissions associated with production, transportation, and combustion of natural gas, including leakage of methane from wells, are comparable to those linked to coal.

Be that as it may, state and federal regulators, along with the courts, have generally shown themselves favorable to new gas-fired generation. Unless gas prices jump significantly from their current lows, utility executives are likely to keep greenlighting these projects.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.