Google’s AI Masters Space Invaders (But It Still Stinks at Pac-Man)

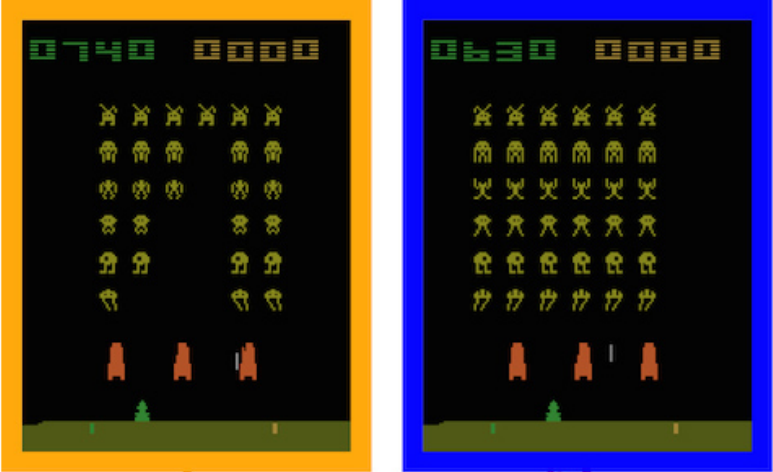

Notch up another win for the machines. Software from Google’s DeepMind artificial-intelligence group has learned to play the classic Atari 2600 game Space Invaders to a superhuman level.

That news comes via a new paper in the scientific journal Nature, which says that the software learned to play 22 classic Atari titles better than an expert human video-game tester could. The work updates an earlier paper on the same software published at an AI conference in late 2013. Back then the software took on seven titles, and it could only outperform humans at three. At the time DeepMind was an independent startup.

Not long after, DeepMind was acquired by Google for $628 million, and Google CEO Larry Page was showing the software off at the 2014 TED conference. MIT Technology Review delved into its workings in a profile of DeepMind’s leader Demis Hassabis last December (see “Google’s Intelligence Designer”).

Hassabis’s team, called Google DeepMind, has now developed a more complex, tuned-up version of the “deep Q-network” that took on 49 different Atari games. That it became a superhuman player of 22 of them, including Space Invaders, underlines the power of DeepMind’s technology. But the way it lagged human performance at 20 others, and only matched it for the rest, is a reminder that even this unusually capable software still has only limited intelligence.

The classic game Ms. Pac-Man neatly illustrates the software’s greatest limitation: it is unable to make plans as far as even a few seconds ahead. That prevents the system from figuring out how to get across a the maze safely to eat the final pellets and complete a level. It is also unable to learn that eating certain magic pellets allows you to eat the ghosts that you must otherwise avoid at all costs.

DeepMind’s software is essentially stuck in the present. It only looks back at the last four video frames of game play (just a 15th of a second) to learn what moves pay off or how to use its past experience to choose its next move. That means it can only master games where you can make progress using tactics that have very immediate payoffs. That’s limiting, even if it works well for some Atari games. Even so, DeepMind’s software has proved capable of working out seemingly complex strategies, like digging the ball around the back of the wall of blocks in the game Breakout, something expert human players do.

Hassabis says that his team is working to expand the software’s attention and memory span, as well as to make it capable of exploring a game more systematically than just by making random moves as it does today. He says tweaks like that should allow the software to master much more complex environments. Work has already started on having it play games for the Super Nintendo console and early PCs, many of which have simple 3-D environments.

Testing on more and more complex games could even provide a bridge into the real world. “Ultimately the idea is that if this algorithm can drive a car in a racing game, with a few tweaks it will be able to drive a real car,” said Hassabis at a press conference Tuesday.

Don’t expect DeepMind software to take the wheel of one of Google’s autonomous cars any time soon, though. What work is being done to apply the group’s research to real world problems today is focused on the company’s core products such as search, mobile assistant functions, and translation, says Hassabis. “Imagine if you could ask the Google app for something as complex as, ‘Okay, Google, plan me a great backpacking trip through Europe,’ ” he told MIT Technology Review.

Services like mobile assistants and automatic translation are familiar and workable today, but they can be frustratingly limited. Software that can learn to beat you at video games may be exciting, but its first real impact on the world is likely to be bringing new ( you might say overdue) polish to services we already use.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.