Inspired by Wikipedia, Social Scientists Create a Revolution in Online Surveys

Gathering data about human preferences and activities is the bread-and-butter of much research in the social sciences. But just how best to gather this data has long been the subject of fierce debate.

Social scientists essentially have two choices. On the one hand, there are public opinion surveys based on a set of multiple choice questions, a so-called closed approach. On the other, there are open approaches in the form of free ranging interviews in which respondents are free to speak their mind. There are clearly important advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Today, Matthew Salganik at Princeton University in New Jersey and Karen Levy at New York University outline an entirely new way of gathering data inspired by a new generation of information aggregation systems such as Wikipedia. “Just as Wikipedia evolves over time based on contributions from participants, we envision an evolving survey driven by contributions from respondents,” they say.

They say the new approach can yield insights that would be difficult to obtain with other methods. But it also presents challenges for social scientists, particularly when it comes to analyzing the data collected in this way.

Projects like Wikipedia are the result of user-generated content on a massive scale. The question that Salganik and Levy ask is whether surveys could also be constructed by respondents themselves, at least in part.

To find out, these guys have developed a new type of data collection mechanism that they call a wiki survey. This starts with a set of seed questions but allows respondents to add their own questions as the survey involves.

This wiki survey takes a particular form in which respondents are asked to choose between two options: do they prefer Item A or Item B, for example. But crucially, they can also add a new item that will be presented to future participants. So as time goes on, the number of items to choose from increases as respondents suggest their own ideas.

This kind of pairwise survey has a number of advantages. Salganik and Levy point out that this format allows participants to respond to as many choices as they wish. They call this property greediness.

This kind of survey also allows respondents to contribute new items whenever they wish and so is uniquely collaborative. Finally, the pairs presented to new participants can be selected in a way that maximizes learning based on previous responses so a wiki survey can adapt as it evolves.

To test the idea, Salganik and Levy created a free website called www.allourideas.org on which anybody can create a pairwise wiki survey and gather respondents from a target audience encouraged to participate. Since 2010, this website has hosted some 5,000 pairwise wiki surveys that have included 200,000 items and garnered 5 million responses.

Salganik and Levy discuss in detail the example of a survey by the Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability run by New York City Mayor. This organization wanted to understand residents’ ideas about the city’s sustainability plan and integrate any new thoughts.

The Mayor’s Office began with a list of 25 seed items that it asked people to compare in pairwise fashion, while also encouraging participants to add their own ideas. For example, people were asked to choose between “Open schoolyards across the city as public playgrounds” and “Increase targeted tree plantings in neighborhoods with high asthma rates.”

Over four months, 1,436 respondents contributed over 30,000 responses and 464 new ideas to the survey. At the end of the survey, eight of the 10 highest scoring ideas had been contributed by the respondents themselves.

These included ideas that would have been unlikely to emerge through other data gathering methods, such as “Keep NYC’s drinking water clean by banning fracking in NYC’s watershed” and “Plug ships into electricity grid so they don’t idle in port—reducing emissions equivalent to 12,000 cars per ship.”

Salganik and Levy are quick to point out that their method requires substantial further research.

In particular, they need to better understand the consistency and validity of the responses they generate. That could be done by comparing the results to those gathered by other forms of data collection.

What’s more, analyzing the data from pairwise wiki surveys is still something of a statistical experiment. And they offer something of a challenge to the statistical community to find the most efficient ways of extracting information from this kind of process.

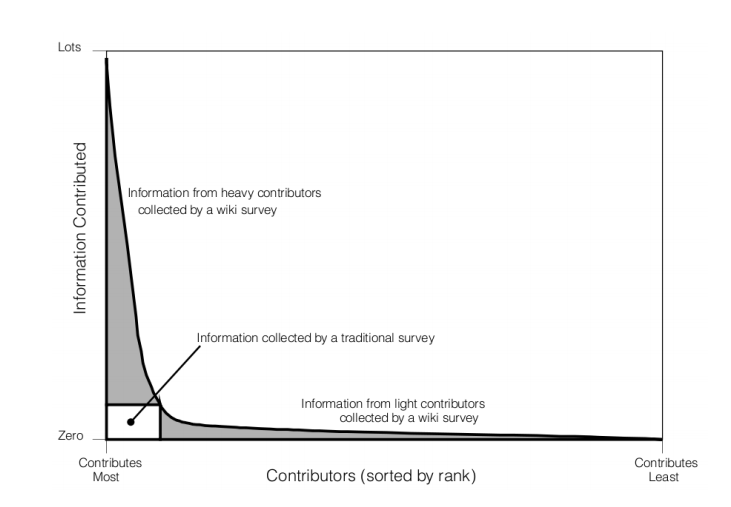

That is an interesting new approach that allows the collection of data that would be difficult to get by other methods. In particular, it allows data to be gathered in a way that reflects the well-known long-tailed distribution of contributors.

For example, on Wikipedia most of the information is intuited by a tiny proportion of editors. “If Wikipedia were to allow 10 and only 10 edits per editor—akin to a survey that requires respondents to complete one and only one form—it would exclude about 95% of the edits contributed,” say Salganik and Levy.

Of course, this kind of bias needs to be accounted for when it comes to data analysis. And therein lies a significant challenge. Time for the statisticians to get busy.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1202.0500 Wiki Surveys: Open And Quantifiable Social Data Collection

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.