Internal waves, whose towering but slow-moving crests can reach heights of hundreds of feet, are hidden entirely within the ocean, invisible on the surface. Yet they can have profound effects on Earth’s climate and on ocean ecosystems.

Now a team including Thomas Peacock, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, has completed the largest laboratory experiments ever used to investigate internal waves. The results solve a long-standing mystery about exactly how the largest known internal waves—those in the South China Sea—are produced.

Seen in cross-section, these waves resemble surface waves in shape. They form in water that is stratified into layers of different density due to changes in temperature or salinity. But these layers, and the huge waves within them, are invisible to the eye.

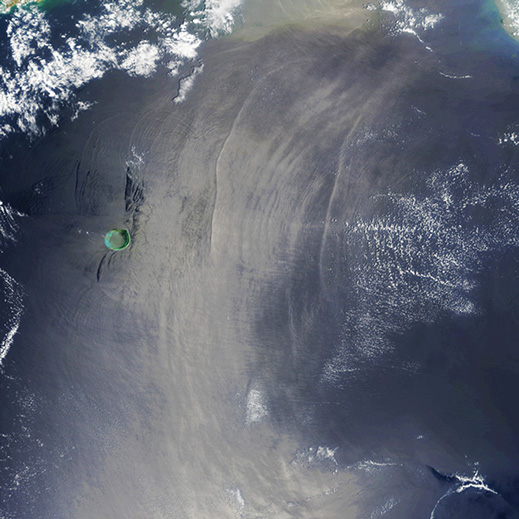

A boundary layer under 100 meters thick separates the colder, saltier water at the bottom of the ocean from the warmer, less salty top layer that extends 100 to 200 meters down from the surface. When part of the lower layer is pushed up by tides or currents interacting with the seafloor topography, the flat boundary layer forms a wave shape whose impact on the spread of ocean surface waves can be detected instrumentally in satellite imagery. And that wave can reach towering heights, travel vast distances, and play a key role in mixing ocean waters, helping drive down surface water that has been warmed by the air, thus drawing heat from the atmosphere down to the seafloor.

Because these internal waves are so hard to detect directly in the ocean, Peacock and a team of French researchers used laboratory experiments to study the waves that interested them: those that form in the Luzon Strait, between Taiwan and the Philippines. “These are the most powerful internal waves discovered thus far in the ocean,” Peacock says. “These are skyscraper-scale waves.” Indeed, they can reach heights of 170 meters (more than 550 feet) but travel at a leisurely pace of a few centimeters per second. “They are the lumbering giants of the ocean,” he says.

The team’s large-scale experiments used a detailed topographic model of the Luzon Strait’s floor mounted in a 50-foot-diameter rotating tank in Grenoble, France, the largest such facility in the world. The tests showed that the strait and a system of ridges within it generate the waves as the tides sweep the stratified water over and through them.

The last major field program of research on internal-wave generation took place off the coast of Hawaii in 1999, but scientists are now more aware than they were then of the role these giant waves play in the mixing of ocean water—and therefore how significantly they affect the global climate.

“It’s an important missing piece of the puzzle in climate modeling,” Peacock says. Right now, global climate models are not able to capture these processes, he says, but it is clearly important to do so: “You get a different answer … if you don’t account for these waves.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.