Heart Implants, 3-D-Printed to Order

It’s a poetic fact of biology that everyone’s heart is a slightly different size and shape. And yet today’s cardiac implants—medical devices like pacemakers and defibrillators—are basically one size fits all. Among other things, this means these devices, though lifesaving for many patients, are limited in the information they can gather.

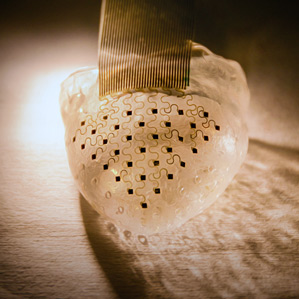

Researchers recently demonstrated a new kind of personalized heart sensor as part of an effort to change that. The researchers used images of animals’ hearts to create models of the organ using a 3-D printer. Then they built stretchy electronics on top of those models. The stretchy material can be peeled off the printed model and wrapped around the real heart for a perfect fit.

The research team has also integrated an unprecedented number of components into these devices, demonstrating stretchy arrays of sensors, oxygenation detectors, strain gauges, electrodes, and thermometers made to wrap perfectly around a particular heart. For patients, this could mean more thorough, better-tailored monitoring and treatment.

One device in need of improvement is the implanted defibrillator, which is attached to a misfiring heart and uses readings from one or two electrodes to determine whether to restore a normal heartbeat by applying an electric shock. With information from just one or two points, the electronics in these systems can make the wrong decision, giving the patient a painful unnecessary shock, says Igor Efimov, a cardiac physiologist and bioengineer at Washington University in St. Louis.

“The next step is a device with multiple sensors, and not just more electrical sensors,” says Efimov. Sensors that measure acidic conditions, for example, could offer an early sign of a blocked coronary artery. Meanwhile, light-emitting diodes and light sensors could provide information about heart-tissue health by identifying areas with poorly oxygenated blood, which is less transparent to light. Light sensors might even help detect a heart attack, since the enzyme NADH, which accumulates during heart attacks, is naturally fluorescent.

Efimov is collaborating on smarter heart implants with John Rogers, a materials scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who has previously made large sheets of thin, stretchy electronics and shown that they can be placed on the heart and other tissues to monitor electrical activity and other functions. This collaboration with Efimov builds on Rogers’s work with his company MC10 to integrate different kinds of sensors into flexible, biocompatible materials (see “Making Stretchable Electronics”).

For the new heart implant, the researchers incorporated multiple kinds of sensors into the same sheets, and they formed the sheets in a way that provides a better fit to the heart’s surface. “Before, we would prefabricate all this on a planar surface,” says Yonggang Huang, a mechanical engineer at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who’s helping design the stretchy electronics. But a flat material can wrinkle as it is wrapped around the heart.

To eliminate these wrinkles, which can interrupt contact between the tissue and the electronics, Efimov’s team built the devices on a 3-D-printed plastic model, designed using an image of an individual heart. They created the actual device on top of the plastic model, first laying down sensors and other electronics (and the wiring that connects them) and then coating them with a stretchy, FDA-approved polymer. Finally, the whole thing can be peeled off and wrapped around the heart.

The researchers used optical images of rabbits’ hearts to demonstrate the concept. To make devices for patients, they would use CT or MRI scans of each person’s heart. The work was described online recently in the journal Nature Communications.

Nicholas Peters, head of cardiac electrophysiology at Imperial College London, says the new equipment could precisely measure multiple heart functions at once—something that’s not been possible before. Doctors could use the sheets to map not only electrical activity but mechanical function and other aspects of heart health, he says.

“This level of precision of colocalized electrical and mechanical functional measurement has long been sought,” says Peters. “This approach immediately raises the realistic possibility of clinical application in human heart disease.”

“This is a nice use of 3-D printing to get this sock of electronics that fits the individual patient well,” says Zhenan Bao, a materials scientist at Stanford University. Devices made in this kind of custom manufacturing process would probably be more expensive than mass-produced medical devices, but for these kinds of life-or-death applications, the market is likely to bear the cost, says Bao. The volume and quality of the data gathered by these large sensor sheets in the group’s animal studies is impressive, she says.

So far, the researchers have tested their technology on beating rabbit hearts outside the body. The next steps are to show that these devices can work in live animals and then in people.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.