Data Mining Exposes Embarrassing Problems for Massive Open Online Courses

It wasn’t so long ago that the excitement surrounding online education reached fever pitch. Various researchers offering free online versions of their university classes found they could attract vast audiences of high quality students from all over the world. The obvious next step was to offer far more of these online classes.

That started a rapid trend and various organisations sprung up to offer online versions of university-level courses that anyone with an Internet connection could sign up for. The highest profile of these are organisations such as Coursera, Udacity, and edX.

But this new golden age of education has rapidly lost its lustre. Earlier this month, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania reported that the online classes it offered had failed miserably. Only about half of the students who registered ever viewed a lecture and only 4 percent completed a course.

That’s prompted some soul-searching among those who have championed this brave new world of education. The questions that urgently need answering are: what’s gone wrong and how can it be fixed?

Today, Mung Chiang’s research team and their collaborators at Boston University and Microsoft offer their view. These guys have studied the behaviour in online discussion forums of over 100,000 students taking massive open online courses (or MOOCs).

And they have depressing news. They say that participation falls precipitously and continuously throughout a course and that almost half of registered students never post more than twice to the forums. What’s more, the participation of a teacher doesn’t improve matters. Indeed, they say there is some evidence that a teacher’s participation in an online discussion actually increases the rate of decline.

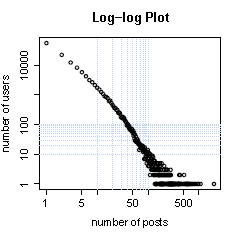

Chiang and co studied the discussion threads associated with 73 courses offered by Coursera. These involved 115,000 students who wrote over 800,000 posts in 170,000 different threads. The team then plotted how the volume of discussion varied through the course and what factors correlate with this decline.

Chiang and co say they’ve found various correlations with the drop. One of these is the amount of peer-graded homework on the course, a factor which moderately increases the rate of decline. More worrying is the discovery that teacher involvement in a thread seems to accelerate the decline (although it also increases the number of posts).

Just how this can be reversed isn’t clear but one potential avenue is to improve the learning experience by making the most valuable posts in discussions more easy to find.

Chiang and co say that posts fall into three categories. The first is small talk, student introductions and the like, that are of little use in completing the course. The second is about course logistics such as when to file homework. And the final category is course-specific questions which are the most useful for students.

The problem is that the useful posts are drowned out by the others, particularly the small talk. “For humanities and social sciences courses, on average more than 30% of the threads are classified as small-talk even long after a course is launched,” say Chiang and co. “Small-talk is a major source of information overload in the forums.”

To help combat this problem, Chiang and co have developed an automated system that spots small talk and filters it out of the firehose. That should help students focus on the useful posts and enhance the learning experience.

Whether that will improve the failing metrics for massive open online courses isn’t clear. But there’s clearly scope for more work to identify the reasons why the courses fail to work for so many students. And if free online education is to get some of lustre back, this work will have to be done quickly.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1312.2159: Learning about social learning in MOOCs: From statistical analysis to generative model

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.