First Direct Measurement of Infection Rates For Smartphone Viruses

One of the great fears with mobile phones is the potential for pandemic viral infection. The worry is that mobile phones are uniquely susceptible to viruses because they connect to the web, phone network and to each other providing numerous routes for infections to spread.

But data showing the actual level of viral infection is hard to come by. Estimates range from more than 4 per cent of Android devices to less than 0.0009 per cent of smartphones in the US. That’s a huge spread.So where does the truth lie?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Hien Thi Thu Truong at the University of Helsinki and a few pals. These guys have measured the rate of malware infection on a large number of Android phones, the first independent group to do this. The bottom line? Infection rates are relatively low–for the moment.

These guys measured viral infection using a battery monitoring app known as Carat. This was designed and built at UC Berkeley and the University of Helsinki by many of the team involved in this work. Carat analyses a smartphone’s energy usage and then highlights apps that are hogging the battery.

It’s a collaborative app and so compares the anonymised data from many phones to get the best battery life statistics. But that also makes it a useful indicator of malware infection because it notes which apps are active on all the phones.

In total, Truong and co gathered data from more than 55,000 Android smartphones. They compared the apps they were running against lists of known malware from the Malware Genome dataset, the Mobile Sandbox dataset and from the anti-virus company McAfee.

Interestingly, these datasets are substantially different. That’s because these organisations define malware in different ways, which is itself a telling indicator of the state of malware research for smartphones. “There is no wide agreement among anti-malware tools about what constitutes malware,” say Truong and co.

For this reason, the level of infection varies according to the malware dataset that the usage data is compared against. For Mobile Sandbox it is 0.26 per cent, and for McAfee it is 0.28 per cent. That’s significantly less than the 4 per cent level mentioned above and significantly more than the 0.0009 per cent figure.

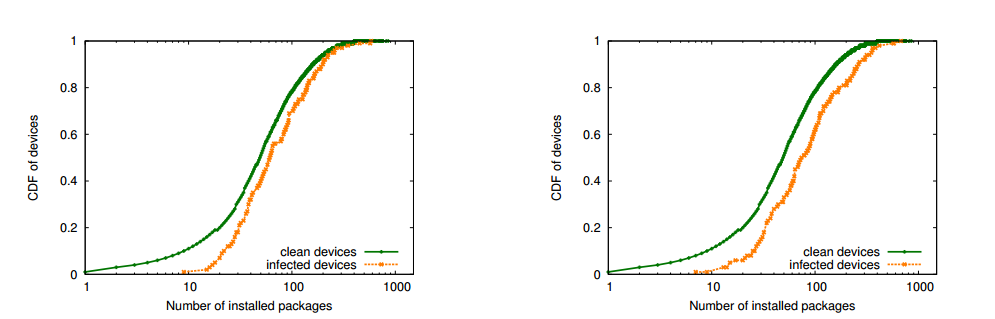

Truong and co say the results suggest a different way to identify smartphones that are at risk of infection. They point out that infected phones also tend to have other apps in common, possibly because the users purchase them all from the same supplier.

So one way to spot smartphones at risk of infection is to look for those that also use these other apps. Indeed, Truong and co say that in their dataset, this approach is five times more likely to identify infected phones than by choosing phones at random. Given the confusion over what constitutes malware, that could turn out to be a useful way of narrowing the field to find infected phones.

Clearly, malware isn’t yet the dark force that many people predicted for the smartphone world. But that doesn’t mean it won’t be in future.

One prediction is that smartphone viruses can only spread like wildfire if they infect a certain proportion of the smartphone population. This is a particular threat if the viruses use more than one transmission mechanism such as Bluetooth of multimedia messaging.

For the moment, current levels of infection seem well below this threshold. The question is for how long.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1312.3245: The Company You Keep: Mobile Malware Infection Rates and Inexpensive Risk Indicators

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.