First Lasing Nanofibres Open the Way for Cheap, Soft Laser Textiles

There was a time, not so long ago, when lasers were exotic devices that lived in specialist labs and relied on a team of experts to keep them going. All that changed when physicists worked out how to make solid state lasers using the same techniques that have made silicon chips so ubiquitous and cheap. Today, if you live in the western world, you’re probably not more than 5 meters away from a laser right now, perhaps in a DVD player, a laser pointer or disc drive.

But despite their ubiquity, lasers are still relatively tricky to make and hard to incorporate into anything other than solid state devices such as computer chips. Physicists have made some progress in doping optical fibers so that they lase.

But these fibers are relatively large compared to microelectronic components such as transistors and stiff compared to organic fibers such as cotton and so have limited utility. It would be impossible to knit a sweater out of optical fibers, for example.

That could change now thanks to the work of Andrea Camposeo at the National Nanotechnology Laboratory of Istituto Nanoscienze-CNR in Italy and a few pals. These guys have found a way to make organic nanofibers that lase at visible wavelengths. The work opens the way to the manufacture of laser textiles, entire sheets of material that emit light using the process of stimulated emission.

To make these nanofibers, Camposeo and co use the straightforward process of electrospinning. This begins with a solution of organic polymer, such as PMMA or polystyrene, which coats a conical surface known as a spinneret.

When placed in an electric field, charge builds up of charge at the tip of the cone causing the liquid to form into a droplet which is then pulled away from the surface, drawing a string of fluid with it. As the solvent evaporates, the molecules polymerize forming a nanofiber.

That’s a well-known and conventional process. The trick that Camposeo and co have perfected is to add some laser dyes to the mix. These are organic molecules that can absorb light at one wavelength and emit it at a higher one. So when bathed in light at the lower wavelength, the medium lases at the higher wavelength.

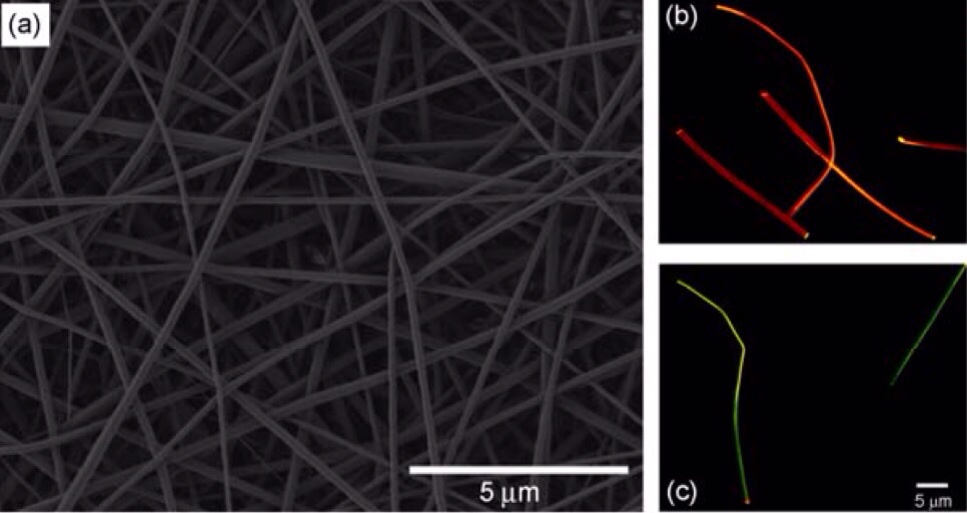

The results look impressive. These guys have electrospun single nanofibers of PMMA mixed with laser dyes to produce fibers with diameters ranging from a few hundred nanometers to a few microns.

And when bombarded with external light, these fibers trap light within them causing the entire fiber to lase. The light can also pass form one fiber to another, where they touch.

What’s interesting about this approach is that the chemical properties of the fibers are easy to modify. Camposeo and co say it is possible to make fibers that lase at a wide range of wavelengths. “These nanostructures can be tailored to emit light in the whole visible and in the near-infrared region,” they say.

There are numerous applications for these kinds of fibers, which can be made at room temperature at little cost. Camposeo and co say that single nanofibers can be used in a wide range of photonic components, at a cost that makes them more or less disposable. They can also form into a kind of matting to create textiles that lase. “We anticipate that these properties can make electrospun polymer mats interesting candidates as light- emitting sources for building active textiles and smart surfaces with large area, for various technical applications,” they say.

That’s an interesting possibility. Camposeo and co do not go into detail about the kinds of things that could become possible with these kinds of components and textiles. So suggestions in the comments section please.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1311.7598: Polymer Nanofibers as Novel Light-Emitting Sources and Lasing Material

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.