Twitter’s Success Offers Hope for Crafty Human Brainpower

Twitter’s listing on the NYSE arguably reflects renewed faith in human traders after Facebook’s error-strewn debut on the more heavily computerized NASDAQ in May 2012. But there’s another, more subtle, reason why Twitter’s success should warm the hearts of those of us who still exist in meat-space: Twitter’s search and advertising system relies on human computers as well as Big Data algorithms.

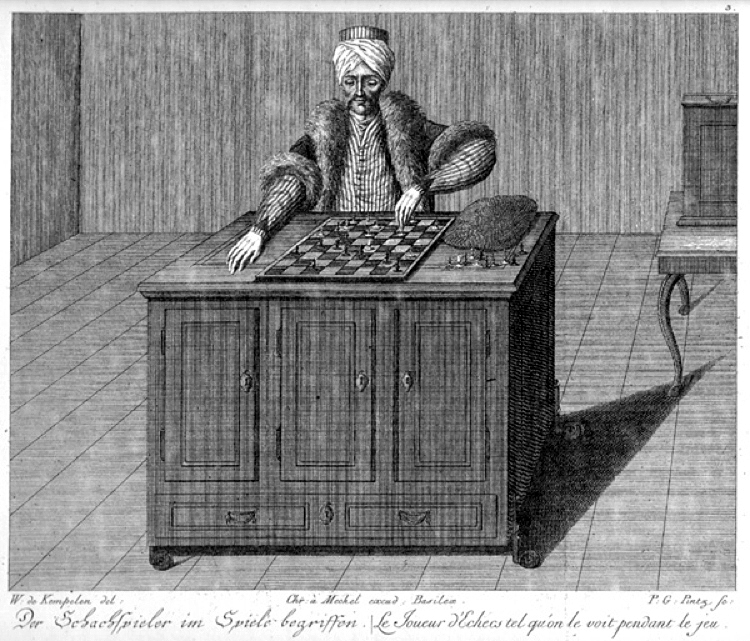

Here’s how that works. When there’s a sudden surge in activity related to a new word or phrase, Twitter’s software collect those strings so that they can be searched for, or matched with ads, but it also automatically feeds them to humans workers to attach appropriate meaning. These workers are employed via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing platform that allows hard-to-compute tasks to be divided up and allocated to humans (the service was named after the chess-playing “automaton” pictured above, which defeated its opponents not using ingenious engineering but thanks to a skilled human player concealed beneath the chess board).

Twitter requires human help because new information often emerges rapidly, and the meaning of that information may be complex, convoluted, and entangled in real-world context. A great example is the phrase #bindersfullofwomen, which gained momentum during the second presidential debate last July. Algorithms that might normally help you find relevant tweets—or might automatically serve relevant advertisements—by looking for clearly relevant strings such as “#Obama,” “#Romney,” “#PresidentialDebate,” simply cannot make sense of this kind of information. Algorithms might match tweets referencing #bindersfullofwomen to ads for Staples of Office Depot, but humans who just watched the debate should know better.

This trend may turn out to be an important in other areas, especially since some experts predict that increased automation will destroy many more jobs than it creates in certain sectos (see “How Technology is Destroying Jobs”).

It’s a trend that I first became aware of in robotics, where some researchers have found that combining human workers abilities with those of robots can be more efficient than using either humans or robots alone (see “Smart Robots Can Now Work Right Next to Auto Workers” and “This Robot Could Transform Manufacturing”).

How human abilities could be merged with information technologies is an even more fascinating to consider. And it’s an idea that actually stretches back for decades, gaining prominence through a paper called “Man-Machine Computer Symbiosis”, published by J. C. R. Licklider. It’s also the subject of a new book by the technology journalist Clive Thompson, “Smarter Than You Think”. For some thoughtful perspective, check out this article in The New York Review of Books by chess legend Garry Kasparov, in which he describes so-called Advanced Chess, where games are held between humans and computer programs working together.

The big question is, will more sophisticated, lucrative, and rewarding, ways of combining human and machine intelligence emerge? If they do, then Twitters hidden army of human helpers could perhaps point to a valuable long-term technological trend.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.