“Spoofers” Use Fake GPS Signals to Knock a Yacht Off Course

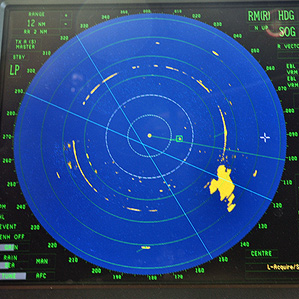

University of Texas researchers recently tricked the navigation system of an $80 million yacht and sent the ship off course in an experiment that showed how any device with civilian GPS technology is vulnerable to a practice called spoofing.

Led by GPS expert Todd Humphreys, the researchers used a handheld device they built for about $2,000. It generates a fake GPS signal that appears identical to those sent out by the real GPS. The two signals reach the targeted system in perfect alignment. The strength of the fake signal slowly ratchets up and overtakes the real one.

The yacht’s captain offered up his boat for the experiment after seeing Humphreys give a presentation at this year’s SXSW conference. The takeover took place in June while the boat was traveling in the Mediterranean off the coast of Italy. From a perch onboard the yacht, the spoofing researchers shifted the ship’s course three degrees to the north. They also convinced the yacht’s GPS system that the boat was underwater.

“[The captain] invited me to basically try kicking the tires of his security system,” Humphreys says. “And yeah—they were flat.”

Until now, the threat of spoofing existed mostly on paper. Humphreys’s team had demonstrated the device in experiments with unmanned aerial vehicles. Those tests established that the technology can work from up to 30 kilometers away, Humphreys says.

Now the yacht experiment shows it can be used to fool a navigation system in the real world. This has implications for any system that relies on civilian GPS—a list that includes commercial aviation, smartphones, and the stock market.

“Civilian GPS is not encrypted and not authenticated, so that means it’s entirely predictable,” Humphreys says. “Predictability is the enemy of security.”

Although there is no evidence that spoofing has been used maliciously, other researchers are developing preëmptive solutions.

Mark Psiaki at Cornell University, a former adviser of Humphreys, has been at the problem for several years. Psiaki’s group has a patent pending on a device that would help civilian GPS piggyback off military signals. In this scenario, incoming civilian GPS signals would be compared to military GPS signals that are broadcast on the same frequency. Although the military’s GPS is encrypted, it contains some distinctive features that indicate its relationship to the true civilian GPS signal.

The signals would be processed by one or more intermediate receivers in a secure location unlikely to be spoofed—such as the middle of a desert. However, this means that the solution would require substantial infrastructure to work on a large scale, with receivers spread out in desolate areas around the country.

A simpler answer might be better. Psiaki’s team has built a modified GPS receiver that wiggles its antenna back and forth a couple of inches at a high frequency. Moving the GPS antenna like this alters a characteristic of the incoming signal called the carrier phase. True GPS signals arrive from multiple locations, and this will be evident when looking at the differences in their carrier phases. Fake GPS signals, which are broadcast from a single location, will show the same signature in each carrier phase.

Psiaki’s team tested a prototype based on this idea last year while Humphreys was demonstrating his spoofing device on a drone helicopter. Psiaki says his group detected the spoofing attempt. “If we’d taken [our prototype] out on the yacht, the yacht would not have been fooled,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.