Laser System Tracks Iceberg Evolution and Ocean Temperature

Understanding the temperature of the Arctic ocean and the way icebergs form and melt is hugely important for climate models. A new laser tracking technology should help

Having been a scientific backwater for much of the 20th century, the Arctic has recently become the subject of furious interest and study. That’s partly because of the discovery that the region is sensitive indicator of climate change and partly because of its natural resources that various countries are vying to exploit.

So understanding the climate and ecology of the Arctic has become a pressing goal. One technology that has made a significant difference is satellite remote sensing which can monitor surface temperatures over large areas by measuring the amount of infrared radiation it emits.

But this technique has important limitations when it comes to water temperature. So today, Alexey Bunkin at the Wave Research Center of the Russian Academy of Science in Moscow and a few pals reveal a new way of measuring water temperature from a distance and say they have tested it in the fjords around the Arctic island of Svalbard.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

The new technique could dramatically improve the accuracy of temperature measurements in seawater and could also be used to spot icebergs that represent a threat to shipping as well as studying their formation and melting in detail for the first time.

First, a little background about the limitations of satellite remote sensing. Oceanologists know that satellite radiometers measure the temperature in just the first few micrometres of water on the surface of the sea and that this can be up to a 1° C colder than the column below.

That’s because in the first stages of freezing, the water forms small ice crystals that float to the surface, coagulate and form so-called frazil ice. It’s the temperature of these ice crystals that dominates the satellite measurements so data taken in this way can significantly underestimate the temperature of the ocean beneath.

In recent years, oceanologists have developed a new technique for measuring the temperature of water at a distance. This technique depends on a phenomenon known as Raman scattering in which the water is zapped by an infrared laser and the scattered light analysed.

At the wavelength of infrared light, the scattering is strongly influenced by the molecular vibrations of the molecules in the water. In particular, the new technique focuses on the vibrations of -OH bonds which depend on the molecules around them. However, this dependency changes with temperature so it’s straightforward to analyse the scattered light and work out the temperature of the water that produced it.

What’s more, the laser light can penetrate the ocean to depths of up to 5 metres so a simple gating mechanism can pick out light from different depths to see how the temperature varies.

Bunkin and co have developed a prototype device that weighs just 20 kg and uses 300 W and so can be fitted to unmanned aerial vehicles or submarines for remote sensing over large areas. It consists of an infrared laser, a power supply and a spectrograph all of which is controlled by a PC.

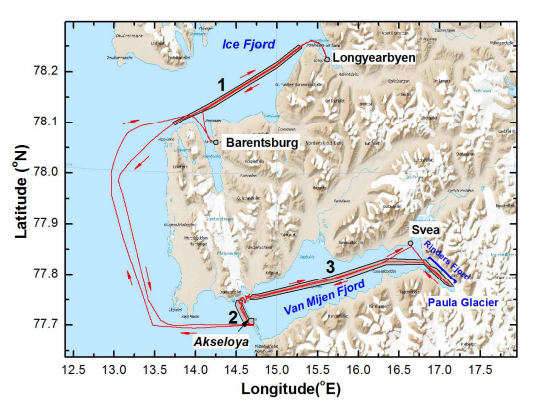

The work that they report today is how they put this device through its paces for the first time by fitting it to a research vessel that they sailed around Svalbard, analysing the property of water in its fjords.

The results are impressive. They show how it is possible to measure the temperature of water at depths of up to a metre or so, even where there is frazil ice on the surface. It turns out that the water temperature in the Arctic fjords varies from around 0°C to 4°C. The team also showed how it may be possible to extend this measurements to depths of up to 5 metres.

This laser system has another advantage – it can measure the concentration of chlorophyll and other particles in the water as well. It showed, for example, that there was little chlorophyll in the water near the snout of a glacier because the ocean there is relatively pure meltwater. However the concentration of chlorophyll increased in other areas of the fjord where chlorophyll had been washed into the ocean.

Bunkin and co say the new technology will be particularly useful for studying the evolution of icebergs. Measuring the temperature of the water around a growing or melting iceberg is extremely dangerous for humans. However, the new remote sensing system can do it at a distance for a long period of time. The results from that kind of study could have an important influence on climate models since one of the major uncertainties is the rate at which ice melts in various sea conditions.

This technology will certainly not replace satellite remote sensing. However, it will provide ground truth data that can be used to calibrate satellite measurements. That will be extremely valuable given the importance of climate models in understanding our planet and the uncertainties that currently dominate them.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1308.1864: Remote Sensing Of Seawater And Drifting Ice In Svalbard Fjords By Compact Raman LIDAR