How Military Counterinsurgency Software Is Being Adapted To Tackle Gang Violence in Mainland USA

In the last 10 years or so, researchers have revolutionised the way military analysts think about insurgency and the groups of people involved in it. Their key insight is that insurgency tends to run in families and in social networks that are held together by common beliefs.

So it makes sense to study the social networks that insurgents form. And indeed that’s exactly what various military analysts have begun to do, including those in the US Army. A few years ago, a group of West Point cadets and offices developed some software for gathering information about the links between the people who make and distribute improvised explosive devices.

In testing this tool in Afghanistan, they found they could perform the same tasks as a traditional analyst in just a fraction of the time.

Now the US Army is adapting this technology to help the police tackle gang violence. Damon Paulo and buddies at the US Military Academy at West Point say there are a number of similarities between gang members and insurgents and that similar tools ought to be equally effective in tackling both.

To that end, these guys have created a piece of software called the Organizational, Relationship, and Contact Analyzer or ORCA, which analyses the data from police arrests to create a social network of links between gang members.

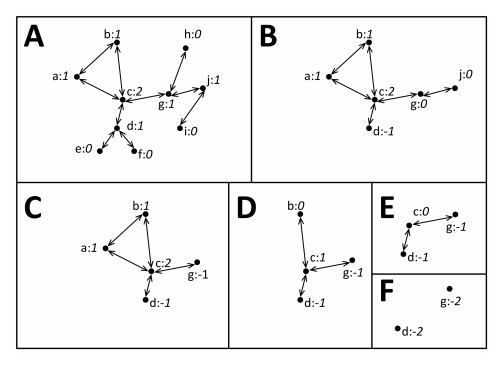

The new software has a number of interesting features. First it visualises the networks that gang members create, giving police analysts a better insight into these organisations.

It also enables them to identify influential members of each gang and to discover subgroups, such as “corner crews” that deal in drugs at the corners of certain streets within their area.

The software can also assess the probability that an individual may be a member of a particular gang, even if he or she has not admitted membership. That’s possible by analysing that person’s relationship to other individuals who are known gang members.

The software can also find individuals known as connectors who link one gang with another and who may play an important role in selling drugs from one group to another, for example.

Paulo and co have tested the software on a police dataset of more than 5400 arrests over a three-year period. They judge individuals to be linked in the network if they are arrested at the same time.

This dataset revealed over 11,000 relationship among. From this, ORCA created a social network consisting of 1468 individuals who are members of 18 gangs. It was also able to identify so-called “seed sets”, small groups within a gang who are highly connected and therefore highly influential.

This approach has also highlighted another aspect of gang culture. The size of the seed sets varies from one gang to another and this turns out to be a useful measure of how centralised the organisation is. Gangs with smaller seed sets are clearly more centralised.

What’s more, ORCA also shows that decentralised gangs have more clearly defined subgroups, such as corner crews. So this feature, known as modularity, is another measure of centralisation.

“Police officers working in the district have told us that gangs of Racial Group A are known for a more centralized organizational structure while gangs of Racial Group B have adopted a decentralized model,” say Paulo and co adding that the results of their analysis seem to clearly show this.

Perhaps most impressive of all, Paulo and co say they did all of the number crunching for this dataset on a standard Windows 8 laptop in just 34 seconds.

The team is currently working to introduce a software in a major metropolitan police department throughout the summer of 2013.

However, there is more work ahead. The next stage is to introduce geographic data into the analysis so that analysts can study how gangs are organised throughout the district. The team also wants to introduce a temporal element to examine how gangs change over time, an important factor since gang members are known to switch allegiances and to regularly start new gangs.

There is clearly some value for the police in this work. “Currently the police are employing this analysis for one district. There are plans to expand to other districts in late 2013,” say Paulo and co.

All that means that the counterinsurgency techniques used by the US Army in Afghanistan may soon be in operation in the urban streets of mainland USA.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1306.6834: Social Network Intelligence Analysis to Combat Street Gang Violence

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.