The Extraordinary “Disco Ball” Now Orbiting Earth

One of the most subtle effects predicted by general relativity is a phenomenon known as rotational frame-dragging. This is caused by a massive spinning body, such as a planet, dragging space-time with it as it turns. That causes any small rotating particles in the vicinity to precess.

Needless to say, the effect is tiny and extremely hard to observe. The difference between Einstein’s predictions and Newton’s is in the region of one part in a few trillion.

Various attempts to measure this in orbit around Earth have had mixed success. The best was a $750 million spacecraft called Gravity Probe B that NASA launched in 2004.

The spacecraft consisted of four small, almost perfectly spherical, gyroscopes each coated with a superconducting layer in which the movement of electrons could be used to measure the rotation.

The idea was to monitor very tiny changes in the way these gyroscopes spun as the spacecraft orbited Earth. In theory, that should have allowed and measurement of frame-dragging with an accuracy of 1 per cent. However, various problems with the spacecraft reduced its accuracy to about 20 per cent.

Astrophysicists would dearly love to get a better measurement but know that the chances of raising the cash required for another experiment of this type are as small as the effect itself.

But there is a much cheaper way of achieving the same goal, at least according to the Italian Space Agency, ASI.

These guys have put a “disco ball” in orbit around Earth and say that carefully measuring its orbit from the ground should produce a similar result.

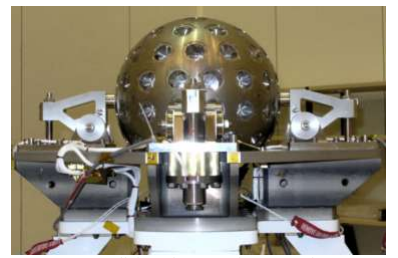

This disco ball is an extraordinary object. It is entirely passive, with no thrusters or electronic components. Instead, it is a tungsten sphere about the size of a football, weighing 400 kg and covered with 92 reflectors that allow it to be tracked using lasers on Earth. These reflectors also make it look like a disco ball.

The ball’s small size large mass make it the most perfect test particle ever placed in orbit, the first aerospace structure ever made from tungsten and the densest object orbiting anything anywhere in the Solar System.

The ball is known as the LAser RElativity Satellite or LARES. The Italians launched it in February last year and have been carefully measuring its orbital characteristics ever since.

Today, Antonio Paolozzi, at the University of Rome La Sapienza and Ignazio Ciufolini, at the University of Salento, described the results of this process.

To be sure, this experiment will be no easy ride. The idea is to measure the ball’s orbit by bouncing lasers off it and then to compare this with the theoretically predicted orbit that takes account of all the different forces that must act on the satellite.

The problem, of course, is that these effects are many, are often subtle and can swamp the signal they are looking for.

To cancel out the effects of the most subtle of these forces, the team need to compare data from LARES with other similar test particles in orbit. As luck would have it, the Italians have a couple of other disco balls already in orbit, called LAGEOS 1 and 2.

Although these aren’t as perfect as LARES, they have been providing data for several years.

Paolozzi and Ciufolini are confident that the analysis will finally produce an accurate measurement of rotational frame dragging. “By adding the LARES orbital data, it will be possible to eliminate also the effects of [these perturbations], thus allowing the achievement of about 1% accuracy,” they say.

That will be impressive, not least because it will have been achieved at a tiny fraction of the cost of Gravity Probe B.

But it’s still too early to pop the champagne corks. As physicists who have attempted to measure this effect can testify, these highly sensitive experiments have a tendency to spring the odd surprise.

Will be watching to see how they fare.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1305.6823 :LARES Successfully Launched In Orbit: Satellite And Mission Description

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.