US Air Force Measures Potato Cannon Muzzle Velocities

The workhorse projectile launcher for physics demonstrations and a certain kind of hobbyist is the potato cannon. A common design involves using compressed air to accelerate a lump of potato out of a tube.

A more powerful option is to drive the potato using the process of combustion and the rapidly expanding gases this creates. Indeed, combustion-driven potato cannons are simpler and easier to build then pneumatic ones.

Perhaps the most popular fuel for such a device is hairspray, which often contains butane or propane.

But a question that will have passed through the minds of many hobbyists is: what is the best fuel for a potato cannon? Today, they get their answer thanks to the work of Michael Courtney at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado and another Courtney at BTG Research in Colorado Springs.

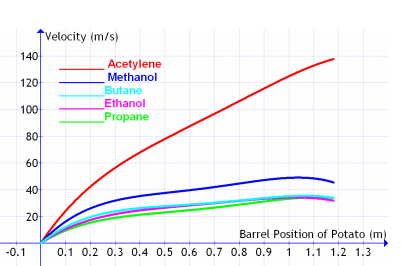

These guys have measured the speed at which an accelerated potato leaves the muzzle of a cannon powered with five different fuels: acetylene, methanol, butane, ethanol and propane.

The experiment is straightforward. They built a potato cannon consisting of a combustion chamber, an electronic trigger and a transparent barrel. Firing the device is a simple matter of filling the combustion chamber with a mixture of air and pulling the trigger.

To measure the potato’s acceleration, they filmed proceedings with a high-speed camera at 2000 frames per second. They then plotted the position of the potato in the barrel against time and calculated the exit velocity when it left the muzzle. They repeated the experiment five times for each propellant.

The results point to a clear winner. Propane, ethanol, methanol and butane all produce muzzle velocities of between 28 and 48 metres per second. But acetylene is in a class of its own, producing a muzzle velocity of 138 metres per second. That’s over 300 mph.

The Courtneys make absolutely clear that this kind of cannon is extremely dangerous and potentially lethal. “Potatoes launched with acetylene were also destructive to wooden boards and plastic objects initially employed as backstops before transitioning to 6mm thick steel plate,” they say.

Potatoes launched in this fashion are definitely ones to steer clear of.

Exactly why this kind of work is useful, the Courtneys don’t say. But it could conceivably be used to design better cannons for…err.. firing T-shirts into crowds at sporting events. Or perhaps for firing chickens into aircraft engines to test their robustness against bird strikes.

Then again, perhaps there is a more sinister explanation, given Michael Courtney’s military employer. Perhaps the potato cannon is set to play an important role in the future arsenal of US Air Force. At least the pilots will never go hungry.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1305.0966: Studying the Internal Ballistics of a Combustion Driven Potato Cannon using High-speed Video

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The great commercial takeover of low Earth orbit

Axiom Space and other companies are betting they can build private structures to replace the International Space Station.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.