How do you make an electronic brain prosthesis that could restore a person’s ability to form long-term memories? Recent experiments by Theodore Berger and his colleagues, including Sam Deadwyler at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and researchers at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, have begun to describe how it might be done.

Last year, the team showed that an implant that records the activity of one set of neurons and directs the activity of another can replace lost brain function in monkeys. The researchers used an array of electrodes to measure the electrical activity of neurons in the animals’ prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in decision making that directs many types of cognitive responses associated with memory. Five monkeys were trained to perform a memory task in which they were shown an image on a screen and then had to use hand movements to steer a cursor to that image when they were subsequently shown a collection of clip-art pictures.

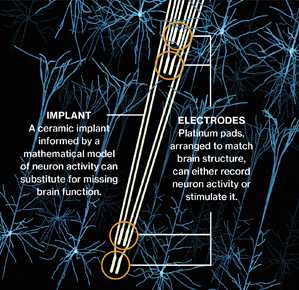

The monkeys’ neural activity was recorded by a tiny ceramic-enclosed electronic device and relayed to an external computer. In the first part of the experiment, the researchers analyzed the brain activity they had recorded from the cortex. But then came the hard part. Memory is formed when one set of neurons processes the signals from another set, but how can you replicate this processing in an electronic device? First, you have to figure out the code the brain is using. From the initial recordings, the research team was able to extrapolate what’s called a MIMO model—short for multi-input/multi-output. This type of mathematical model can characterize the neural firing patterns detected by the electrode implant and, after processing the patterns, spit out the signals that instruct other neurons to form the appropriate memory.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.