Astronomers Calculate Orbit of Chelyabinsk Meteorite

On 15 February at 0920 local time, a huge fireball raced across the skies above the Chelyabinsk region of Russia. This meteorite then exploded creating a shockwave that injured more than 1000 people.

The incident was captured on numerous webcams, security cameras and dashcams in the region and these videos were widely distributed on the web.

The following day, Stefen Geens, who writes the Ogle Earth blog, pointed out that these cameras formed an ad-hoc sensing network that had gathered significant data about the trajectory and speed of the meteorite. He used this data and Google Earth to reconstruct the path of the rock as it entered the atmosphere and showed that it matched an image of the trajectory taken by the geostationary Meteosat-9 weather satellite.

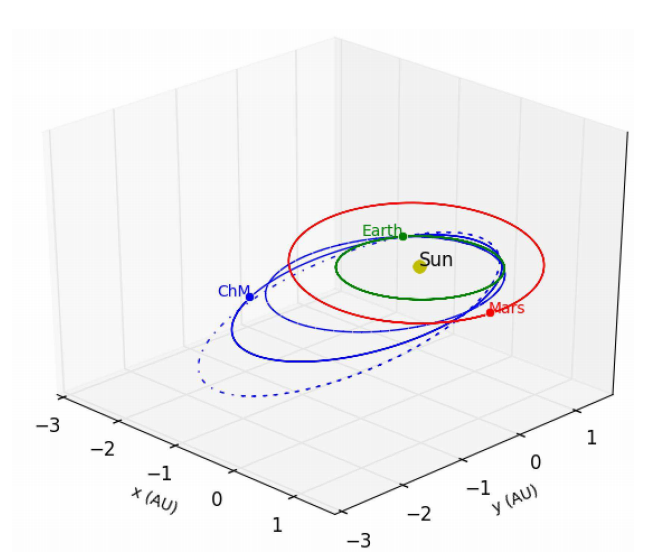

Today, Jorge Zuluaga and Ignacio Ferrin at the University of Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia, take this approach a step further by reconstructing the meteorite’s original orbit around the Sun.

The recordings from traffic cameras have precise locations and well-maintained time stamps. The location of the meteorite impact with the ground is also recorded by a hole in the ice sheet covering Lake Chebarkul, 70km west of Chelyabinsk. Together with the trajectories shown in various YouTube videos, these guys used simple trigonometry to calculate the height, speed and position of the meteorite as it fell to Earth.

Calculating the rock’s orbit around the Sun is a more complicated affair. This depends on six critical parameters which must all be estimated from the data. Most of these are related to the point at which the meteorite becomes bright enough to cast a noticeable shadow in the videos, its ‘brightening point’. They include the meteorite’s height, elevation and azimuth at this point as well as the longitude and latitude on the Earth’s surface below. The velocity is also crucial.

“According to our estimations, the Chelyabinski meteor started to brighten up when it was between 32 and 47 km up in the atmosphere,” say Zuluaga and Ferrin, who estimate the velocity at between 13 km/s and 19 km/s relative to Earth.

They then calculated the likely orbit by plugging these figures into a piece of software developed by the US Naval Observatory called NOVAS, the Naval Observatory Vector Astrometry. This allowed them to include the gravitational influence on the rock of the Moon and the 8 major gravitational bodies in the Solar System.

Their conclusion is that the Chelyabinsk meteorite is from a family of rocks that cross Earth’s orbit called Apollo asteroids.

These are well known Earth-crossers. Astronomers have seen over 240 that are larger than 1 km but believe there must be more than 2000 others of similar size out there.

Smaller Earth crossers are even more common. The sobering news is that astronomers think there are some 80 million about the same size as the one that hit Russia.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1302.5377: A Preliminary Reconstruction of the Orbit of the Chelyabinsk Meteoroid

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.