The States with the Riskiest Voting Technology

Next Tuesday’s presidential election will likely be extremely close, magnifying the potential impact of vote-counting errors. So it could be problematic that several states rely on computerized voting machines that don’t print out a paper record that can be verified by voters and recounted by election officials if necessary.

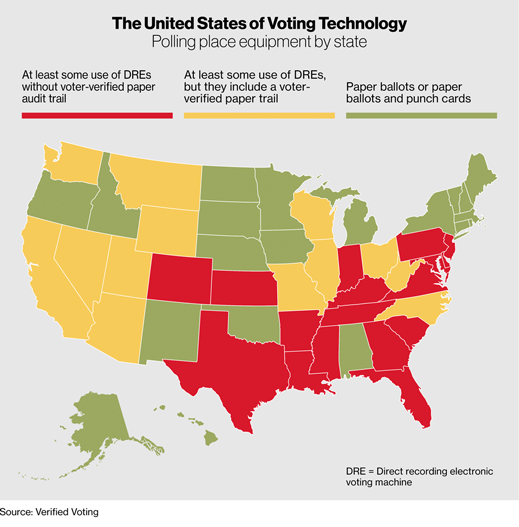

Such machines are in use in 17 states, as indicated in red on the map above. Computer scientists and fair-election advocates have warned for years that potential software malfunctions are possible threats to the integrity of elections in counties and states that use these machines.

Another 13 states, including battleground states such as Nevada, Wisconsin, Ohio, and North Carolina, have at least some polling stations that use voting machines with a precautionary measure: a receipt that can be checked later—a so-called voter-verified paper audit trail. These machines are still vulnerable to software glitches, but voters at least have a chance to spot errors and make sure their vote gets registered and recorded accurately.

Most of this computerized equipment—direct recording electronic voting machines, or DREs—has been introduced since federal legislation was enacted in 2002 that allocated $4 billion toward modernizing the voting process. There are several makes and models, and user interfaces vary, but all rely on computers to register and store votes. This makes them vulnerable to software bugs that could undercount or overcount votes. The DREs that don’t produce paper records are considered the riskiest because a malfunction in such machines could be impossible to detect, much less fix.

These warnings, combined with reports of voting machine problems—1,800 were reported to election hotlines in 2008, and 300 during the 2010 midterm elections, according to a report by authors from the Verified Voting Foundation, Rutgers Law School, and Common Cause—have led many states to avoid or replace e-voting machines. Instead they employ paper ballots that can be read by optical scanners. Computer scientists who have studied election technology say this method is safer than DREs.

In contested states like Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—which depend heavily on paperless DREs—a glitch involving just a small number of votes could change the election’s outcome. Florida, another state whose polls show a thin margin between President Obama and Mitt Romney, has paperless DRE machines available for disabled voters, because the technology is considered a way to improve voting accessibility.

This story was updated on November 1, 2012, to correct the status of Texas, which has some DRE machines that do not produce a paper record.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.