Glass without Glare

Tired of having your glasses fog up when you venture out of an air-conditioned building on a hot day? MIT researchers think they’ve found the solution—a way to eliminate most fogging, glare, and even dirt from glassy surfaces.

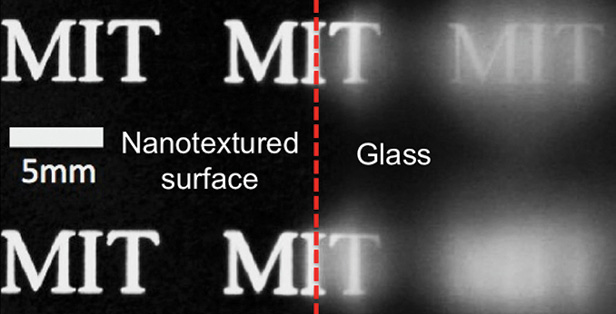

The new multifunctional glass has a nanotextured surface featuring an array of tiny conical bumps that help it resist dirt, fogging, glare, and water droplets, the researchers say.

Ultimately, they hope it can be made using an inexpensive manufacturing process that could be applied not only to eyeglasses and other optical devices, such as microscopes and cameras, but also to solar panels, car windshields, the screens of smartphones and televisions, and even windows in buildings.

The technology, which came from research led by graduate students Kyoo-Chul Park and Hyungryul Choi under the guidance of mechanical-engineering professors George Barbastathis and Gareth McKinley and chemical-engineering professor Robert Cohen, was described earlier this year in ACS Nano.

Photovoltaic panels can lose much of their efficiency as dust and dirt accumulate on their surfaces. But a layer of the self-cleaning glass could help prevent that problem, Park says. The glass’s antireflective quality would further increase the panels’ efficiency.

The key is a surface pattern that consists of nanoscale cones, five times as tall as they are wide, that are coated with a hydrophobic substance. The size and spacing of the cones helps make water droplets bounce off, and the near-vertical surfaces transmit light instead of reflecting it. These features are made using a new patent-pending method, with techniques adapted from the semiconductor industry.

Researchers begin by coating glass with several thin layers, including a photoresist layer (a material that can be etched away by a chemical solution but resists etching wherever it has not been exposed to light). The coated glass is then illuminated in a grid pattern, allowing the photoresist layer to be etched away, leaving circular pillars in the spaces between the grid lines. Successive etchings gradually erode these pillars into conical shapes.

Ultimately, glass or transparent polymer films might be manufactured with such surface features simply by passing them through a pair of textured rollers while they are still partially molten; the process would add little to the cost of manufacturing, the team says.

The researchers drew their inspiration from nature, where textured surfaces ranging from lotus leaves to the carapaces of desert beetles often fulfill multiple purposes. Although the arrays of pointed cones appear fragile when viewed microscopically, the researchers say they should be resistant to a wide range of forces, from impact by raindrops in a strong downpour to direct poking with a finger. Further testing will be needed, though, to demonstrate how well the surfaces hold up over time in practical applications.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.