The Dog Days of Solar

The solar industry has done a spectacular job lowering costs in the past three years, slashing per-watt costs in half. But that price freefall, driven by the massive scale-up of Chinese manufacturers, has put dozens, if not hundreds, of solar companies on the endangered list. To survive, fledging solar technology companies are rethinking strategies that seemed rock solid just a few years ago.

The danger is clear. Abound Solar went out of business earlier this summer because it simply couldn’t stay ahead of the blistering pace of industry cost reductions (see “Abound Solar: Another Solar Casualty”). Its demise follows the spectacular collapse of Solyndra and bankruptcies, plant closings, and restructurings at many other solar providers.

So how can solar startups survive? The challenge isn’t lack of innovation or financing (see “Can Energy Startups Be Saved”). In the U.S., innovative solar startups have attracted billions of dollars in venture capital and government loans. But even with compelling technology, smaller players face the powerful headwinds of competing against giant incumbent providers with access to large amounts of cheap capital, all while needing to work out the kinks of a new production process at scale.

The story of 1366 Technologies, based in Lexington, Massachusetts, illustrates just how difficult it is to introduce new technology in a volatile supplier market. Of the many recent solar startups, the MIT spin-off has been notable for playing its cards right. In contrast to riskier startups that spent vast sums of money designing special equipment for making new types of thin-film solar cells and panels, 1366 focused on improving the existing silicon manufacturing process, which is more dominant today than ever. And it tackled a big problem: the high price of solar-grade silicon.

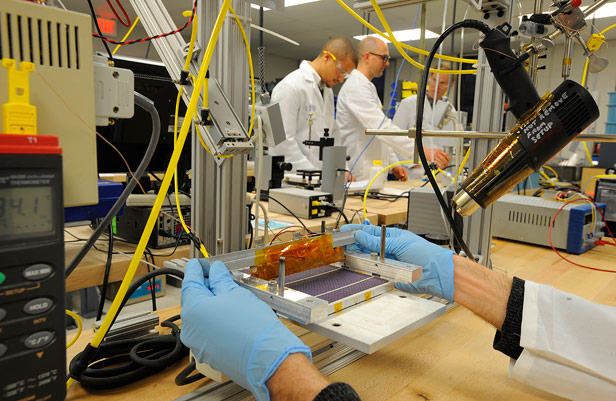

1366 Technologies developed a disruptive process that creates a standard six-inch-square silicon wafer directly from a bath of molten silicon. In the process it eliminated a number of time-consuming steps and potentially sliced the cost of making wafers by more than half (see “Making More Solar Cells from Silicon”). Those wafers are turned into solar cells, and many cells are wired together in a solar panel.

But market conditions have changed dramatically now, and the company finds itself in a tight spot.

Since 1366 was founded four years ago, the cost of polycrystalline silicon has plummeted from hundreds of dollars per kilogram to less than $25. Silicon that cheap makes 1366’s strategy far less compelling, since cutting the cost of producing silicon wafers or cells would have a smaller impact on the end price of solar panels.

1366 Technologies CEO Frank van Mierlo admits that the company was caught by surprise with the dramatic drop in polycrystalline silicon prices during the last year. Still, he says, its planned 30-megawatt demonstration plant will be able to sell wafers at competitive prices and comparable efficiency. The company’s process also results in lower capital costs—since fewer machines are required—and a more consistent yield, he says.

Either by luck or design, the company, which has kept its head count low and operates in a no-frills office, has been very frugal. That means it has enough cash to survive until 2015, van Mierlo says. It will finance its demo plant on its own and it hasn’t yet drawn from a $150 million loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Energy to build a planned 1,000-megawatt plant, which will require other investors. It’s also gotten a strategic partner with Korean industrial giant Hanwha Chemical, which could purchase some of the wafers it intends to make.

“Absolutely, the bar has been raised—the cost targets have to be more aggressive than ever,” van Mierlo says. “But the value of any technology improvement is much higher than it was a decade ago because a much bigger industry can take advantage of it.”

Facing the same tough market forces, other solar companies are trying alternative routes to market, recognizing that going it alone is not a viable option anymore. Twin Creeks Technologies is a startup based in San Jose, California, that also designed a process that cuts the cost of making cells in half by using less silicon while maintaining the same efficiency (see “Startup Aims to Cut the Cost of Solar Cells in Half”). Rather than make cells itself, though, it plans to sell its highly specialized equipment to solar manufacturers looking for a competitive edge. Since launching in March, it has yet to sign on any customers, but a company representative says Twin Creeks is in negotiations and expects to have customers this year.

Another strategy is to make a highly differentiated product, not just one that incrementally cuts production costs or improves cell efficiency.

Silicon Valley-based startup Solexel claims it will be able to produce cells for 42 cents a watt in volume by 2014. That alone will allow it to stay ahead of the industry’s downward-sloping price curve, but the company’s technology has other advantages, says Mark Kerstens, the chief sales and marketing officer. The efficiency is higher than average silicon cells, the panels are all black and aesthetically pleasing, and each cell can be controlled individually, which means less power loss from shading, he explains. “Being a one trick pony is very challenging these days,” Kerstens says. The other requirement to survival is having access to lots of money, not just from venture-capital types but also from strategic investors such as large industrial companies and solar manufacturers. In addition to providing capital, they can be potential customers and help validate the technology in the eyes of others.

To commercialize its thin-film technology, startup Stion forged deals with two Asian manufacturers, which allowed it to bring its product from the lab to factory without having to raise billions on its own. TMSC of Taiwan invested in the company and made its first-generation product, and then Stion took another investment from Korean manufacturer Avaco to produce its next-generation panels. It also benefited from incentives to manufacture in Mississippi.

Solexel, too, tweaked its business plan in light of the high cost of scaling up. Instead of making complete panels, it decided to just make its proprietary cells and outsource panel production, and it intends to form a joint venture for cell production. With money to ride out a few years and access to a government loan, 1366 Technologies is “plowing ahead” with its original plan to sell its wafers into the silicon supply chain, van Mierlo says.

If all else fails, some solar companies may license their intellectual property to other manufacturers, although that’s the least interesting path financially. Many upstart solar companies did the right thing by betting on new technologies to bring the cost of solar power closer to that of fossil fuels. In the end, though, market woes may trump their technical advances.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.