Can Japan Thrive without Nuclear Power?

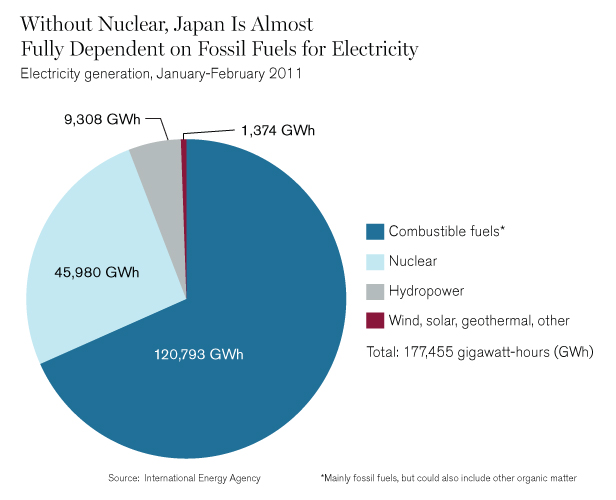

This month, Japan shut down the last of its 54 nuclear reactors. When and if any of those reactors are to be restarted is uncertain. One thing is for sure, though: as long as it is without nuclear power, Japan will be almost completely dependent on imported fossil fuels.

Japan has the third most nuclear generating capacity in the world, behind the U.S. and France. Just before the devastating earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, nuclear power was the source of just under 30 percent of the country’s electricity. Hydropower and other renewable power sources accounted for less than 10 percent. The rest came from fossil fuels—the vast majority of which came from foreign nations, since Japan has few fossil-fuel resources of its own.

Japan’s heavy dependence on foreign oil was exposed as a major vulnerability in 1973, after oil-producing countries in the Middle East imposed an oil embargo. In order to help protect itself from future shocks, the country accelerated its nuclear program, which had begun in the 1950s. Still, half of the nation’s primary energy supply in 2010 came from oil, around 85 percent of which was imported from the Middle East.

The chart above shows how Japan’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil has changed over time, dropping down below 70 percent following the oil crises and then rising again because non-Middle Eastern countries such as China and Mexico began reducing crude exports.

Since March 2011, nuclear generation in Japan has been gradually declining, and the country has replaced it with foreign fuels. Japan’s Institute for Energy Economics estimates that the country spent $50 billion more on fossil-fuel imports ($30 billion for electricity generation) in fiscal year 2011. That means it emitted around 2 percent more carbon dioxide than during 2010—while producing less energy.

If its reactors remain idle this year, predicts the Institute for Energy Economics, Japan will spend nearly $60 billion more than in 2011 on foreign oil, natural gas, and coal. And carbon-dioxide emissions could rise 5.5 percent.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.