Do-It-Yourself Solar

Today, most solar cells are manufactured in high-tech facilities with hospital-like clean rooms. But within a few years, people in remote villages in the developing world could be making their own photovoltaic cells at home, using crop waste.

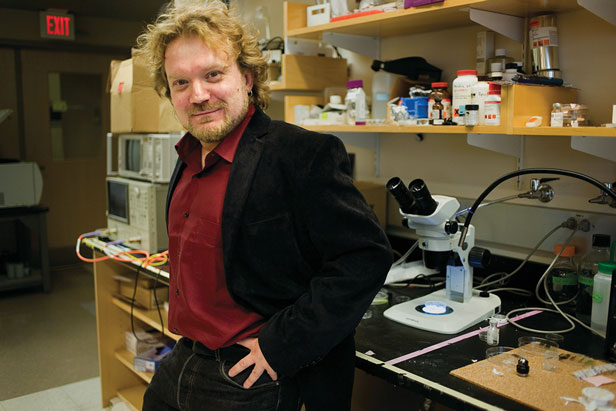

That’s the vision of Andreas Mershin, a researcher at the MIT Center for Bits and Atoms, building on a project begun eight years ago by Shuguang Zhang, a principal research scientist at the MIT Center for Biomedical Engineering. Mershin says that within a few years a villager in a remote, off-grid location could take a bag of inexpensive chemicals developed by his team, “mix it with anything green, and paint it on the roof” to start producing power to charge cell phones or lanterns.

Zhang’s original work used photosystem-I (PS-I) complexes, the tiny structures within plant cells that carry out photosynthesis. He and his team extracted the PS-I complexes from spinach by pulverizing the leaves in a blender, stabilized the structures chemically, and deposited them in a layer on a glass substrate that could—like a conventional solar cell—produce an electric current when exposed to light. But creating such solar cells required expensive chemicals and equipment, and the devices were very inefficient.

Now Mershin says the process has been simplified enough to be replicated in virtually any lab, letting researchers around the world improve upon it. The new system, which converts 0.1 percent of light’s energy to electricity, is 10,000 times more efficient than the previous version but still needs to improve another tenfold to become useful, he says.

The key to the improved efficiency, Mershin explains, was finding a way to expose much more of the PS-I surface area to the sun. He made a tiny forest of zinc oxide nanowires, which serves as a supporting structure for the light-harvesting material. “You can use anything green, even grass clippings,” he says. The nanowires also carry the flow of electrons generated by the PS-I complexes. “It’s like an electric forest,” he says.

The new process “can be very dirty and it still works, because of the way nature has designed it,” says Mershin. “Nature works in dirty environments—it’s the result of billions of experiments over billions of years.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.