Antineutrino Detectors Can Spot the Destruction of Weapons-Grade Plutonium

Nuclear reactors emit tell-tale antineutrinos that could be used to verify when they are burning weapons grade plutonium.

One of the problems in dismantling nuclear weapons is what to do with the leftover weapons grade plutonium.

An obvious answer is to burn it inside mixed oxide nuclear reactors, so-called because they burn a mixture of uranium and plutonium oxides. The process of fission destroys the plutonium, ensuring that it can no longer be used.

But there’s a problem. What if the country in question switches the plutonium for something else, plain old uranium perhaps? In this scenario, this hypothetical state could trick the world into thinking it had disarmed when, in fact, it had stockpiled the plutonium instead.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

You’ve read all your free stories.

MIT Technology Review provides an

intelligent and independent filter for the

flood of information about technology.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

The issue of verification keeps nuclear proliferation experts awake at night. So they’ve been busy looking for a way for observers to tell what a reactor really is burning.

Today, Anna Hayes and friends at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico say they’ve come up with just such a technique: the trick, they say, is to look for the antineutrinos that the reactor produces.

In recent years, nuclear experts have conducted a number of tests in which they’ve monitored the antineutrino output from reactors. In principle, this technique could be used to spot illicit reactors and, on this blog, we’ve looked at this technology here and here.

The detectors consist of a vat of gadolinium-containing liquid surrounded by shields to screen out unwanted signals and detectors looking for the tell tale ones of an antineutrino reaction. This consists of a double energy pulses—the first from a positron-electron annihilation and the second from a neutron capture by a gadolinium nucleus.

Now Hayes and co say these kinds of detectors can be used to determine not just whether a nuclear fission is taking place but what kind of fuel is involved.

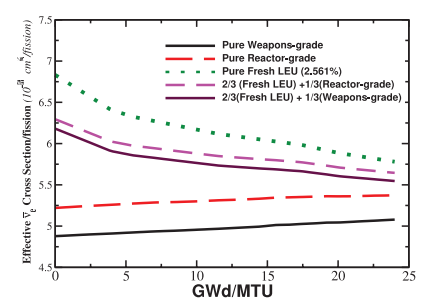

The key is that the fission of plutonium-239 emits only 42 per cent of the antineutrinos that uranium-238 does.

So as long as the power produced by the reactor is known, the number of antineutrinos it emits and how this changes over time can be used to work out the fraction of plutonium involved in the reactions. “The signals are distinguishable by the combination of their magnitudes and their rate of change with fuel burnup,” says Hayes and co.

Of course, things aren’t quite as simple as that in real life. One complicating factor is that the Los Alamos calculations assume that the fuel is fresh. In practice, however, most reactors stagger their fuel input. So at any one time, a reactor will contain some fresh fuel but also older fuels as well. In that case, admit Hayes and co, the antineutrino signals for these will change depending on the core composition.

That doesn’t seem to be a showstopper. And that mean this looks like a promising technology that could play an important role in verifying the destruction of plutonium in future.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1110.0534: Theory of Antineutrino Monitoring of Burning MOX Plutonium Fuels