When you think of electric cars, you don’t usually imagine pulling in to a filling station, saying “Fill ‘er up!” and zipping out minutes later. But that could change within the next few years.

A radically new approach developed by researchers at MIT could provide a lightweight and inexpensive alternative to existing batteries for electric vehicles and the power grid. These batteries could even make “refueling” as quick and easy as pumping gas into a conventional car—only in this case, what’s pumped in would be a thick black goo. Alternatively, the whole battery pack could be rapidly swapped out.

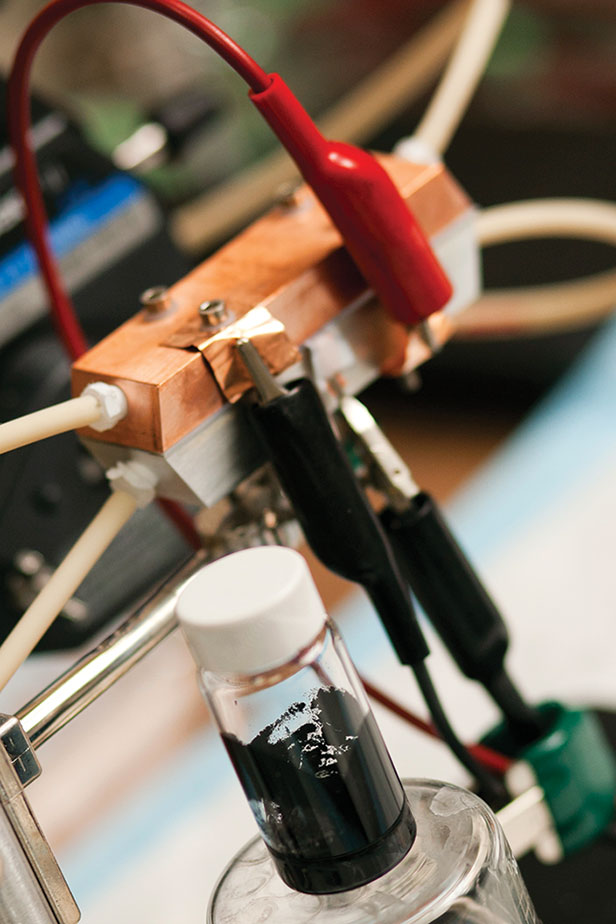

The new battery relies on an innovative architecture called a semi-solid flow cell, in which the positive and negative electrodes, or cathodes and anodes, are composed of particles suspended in a carrier liquid to form a mixture that the researchers jokingly refer to as “Cambridge crude.” The positive and negative suspensions are stored in two tanks and pumped through two sets of pipes into a reaction chamber (or more specifically, a stack of chambers), where they are separated by a barrier, such as a thin, porous membrane.

The chemical reaction in the chambers is essentially the same as that in an ordinary lithium-ion battery. One key difference is that the flow battery’s system for storing energy is physically separate from its system for discharging the energy when needed. Its energy capacity—the amount of energy it can store—is determined by the size of the tanks; its power capacity, or the rate at which it can deliver its charge, is determined by the size of the reaction chamber.

The team set out to “reinvent the rechargeable battery,” says Yet-Ming Chiang ‘80, ScD ‘85, who developed the idea with a fellow professor of materials science, W. Craig Carter, and Mihai Duduta ‘10, graduate student Bryan Ho, and others.

The key insight was that it would be possible to combine the basic structure of a little-known and low-energy-density technology called aqueous-flow batteries, which use electrode material dissolved in a liquid electrolyte, with the proven high-energy-density chemistry of lithium-ion batteries. While dissolving a material changes its chemical behavior significantly, suspending bits of solid material preserves the characteristics of the solid, making it possible to take advantage of its high energy density. So the team pulverized the batteries’ solid materials into tiny particles, which can be carried in a liquid suspension that flows like quicksand.

The researchers believe that the technology could halve the size and the cost of a complete battery system, including its structural supports and connectors. Those savings could help make electric vehicles a compelling replacement for gas- or diesel-powered vehicles. A battery could be “refueled” two ways: by replacing the discharged liquid slurry (which would later get recharged at the filling station) or by simply plugging it in to an ordinary outlet to recharge.

The same basic system could work with many different electrode materials. “We’ll figure out what can be practically developed today,” Chiang says, “but as better materials come along, we can adapt them to this architecture.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.