Microsoft Robots Are Coming

Microsoft software is ubiquitous – it’s in most desktop PCs and laptops and even some PDAs and phones. And now it’s headed into robots.

At the RoboBusiness conference this week in Pittsburgh, PA, Microsoft unveiled Microsoft Robotics Studio, a software development tool that represents the company’s first investment in a market that Bill Gates and others believe has as much growth potential as the early PC market once did.

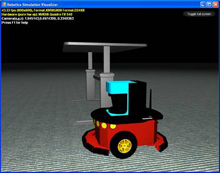

[For images from the Robotics Studio, click here.]

“There are several things about the robotics market that seem to mirror the PC days of the late 1970s,” says Tandy Trower, general manager of Microsoft’s new robotics group. “The key applications that are going to trigger the growth of the technology are still in question. Hardware is fragmented, with little standardization. And there are haves and have-notes – some companies and university labs with the ability to build a whole robot ecosystem from the hardware to the software, and then a wider audience that is anxious to interact with the technology, but just doesn’t have the resources to do it.”

Building a robot these days is as much a programming exercise as a nuts-and-bolts hardware project; even children experimenting with Lego’s popular Mindstorms toy-robot kits must learn how to use graphical programming tools on a PC before they can send a single instruction to their plastic-block creations.

The problem in the grown-up world is that every new robot, even those built by industrial robot manufacturers, requires its own specialized software and programming tools. If there were a single, widely used tool for robot programming, code could be reused on different robots, and robot builders could concentrate on advanced features rather than basic infrastructure, says Trower.

Demonstrating that point, robot makers from Lego to KUKA Robot Group, a German manufacturer of large industrial robots, were on hand in Pittsburgh to show how software written using Microsoft’s tool can run on many different types of robots.

Microsoft’s Robotics Studio, which runs on Windows XP and was released Tuesday as a free preview, includes several components: a programming environment for writing and debugging software for robots that’s similar to Visual Studio, the company’s main tool for writing Windows software; a “runtime” environment that functions as a mini-operating system for robots, executing the code people write using the programming tool; and a simulator that allows users to build virtual models of robots and test how their software would behave on them, without having to build actual hardware.

Trower says Robotics Studio is intended to help the robot industry “bootstrap itself,” the same way Microsoft’s first DOS operating system provided a standard platform that other software writers were then able to use to write a host of applications, such as spreadsheets and word-processing programs, that eventually made PCs indispensable.

Once the toolkit graduates to full-product status later this year, the company will continue to provide it at no charge to academic and educational users, and charge commercial users a few hundred dollars per copy, according to Trower. “The market is just getting started, so it doesn’t make sense to try to pull a large amount of revenue out of it,” suggests Trower. “As the market grows and becomes a commercial reality, that’s where we will recoup our investment.”

Trower believes that PCs and robots are converging – and that Microsoft must invest in robotics if it wants to be a player in personal computing five to ten years from now. “Your PC is getting up off the desktop and beginning to interact in the same environment where you live in new ways, using cameras and sensors and speech technology and a variety of other advanced technologies,” he says. “This is the direction that PCs are evolving.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.