Update 11:20 a.m. Eastern: The Hope probe is officially in orbit around Mars.

Fewer than half of all the spacecraft that have been sent to Mars have actually made it. For every celebrated mission like NASA’s Curiosity Rover, there’s a story of failure like the European Space Agency’s Schiaparelli lander, which crashed into the Martian surface upon descent in 2016.

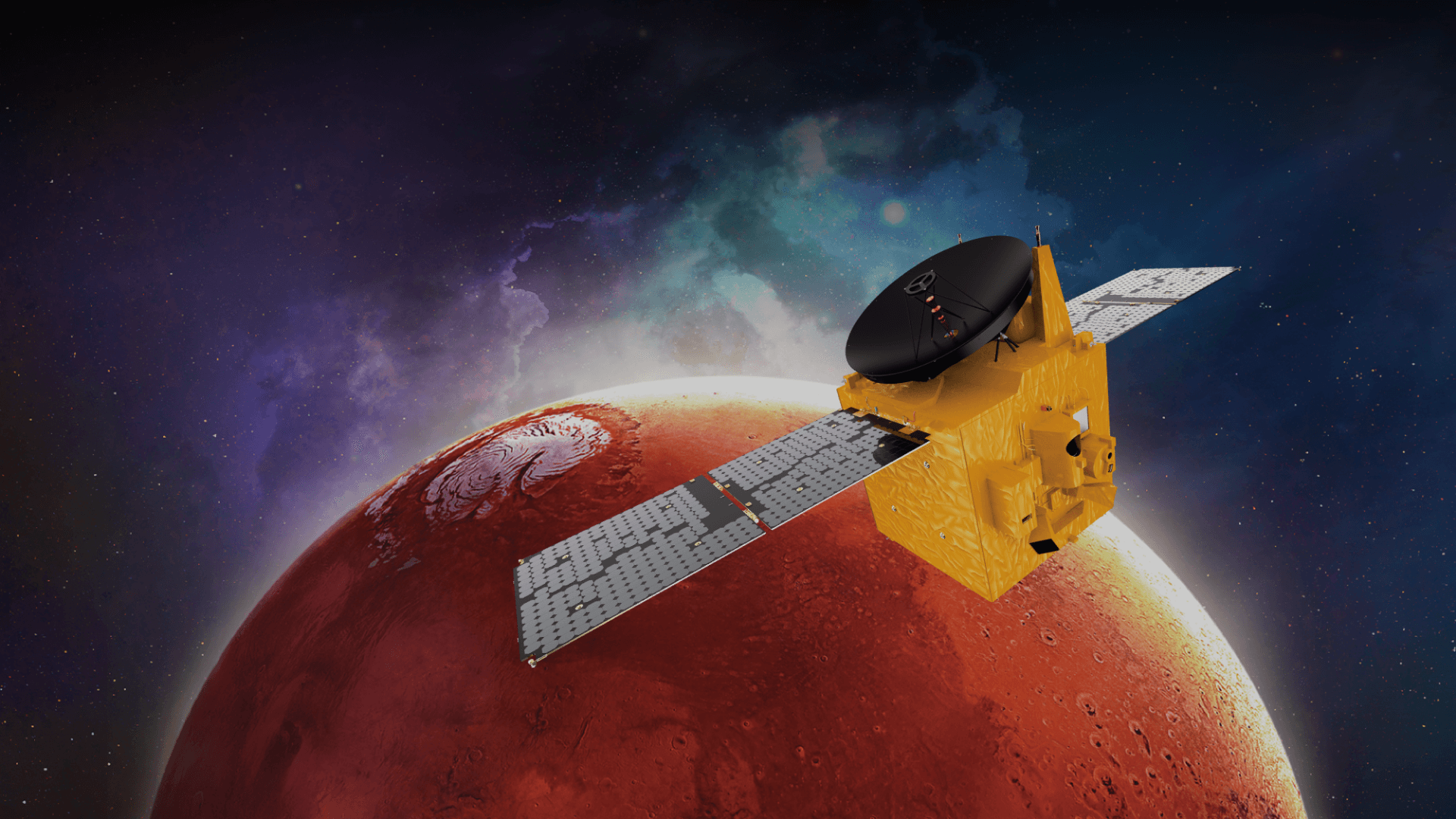

So on Tuesday, February 9, when the United Arab Emirates makes its first attempt to get a spacecraft into Martian orbit, it will be fighting the odds. If the Emirates Mars Mission succeeds, the UAE’s space program will become just the fifth in the world to reach the Red Planet, after the Soviet Union, NASA, the ESA, and India.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

“The team has prepared as well as they could possibly prepare to reach orbit around Mars,” says Sarah Al Amiri, chair of the UAE Space Agency.

There’s some pretty exciting science in store if all things go well. But for the UAE and its partners, the Emirates Mars Mission is about much more than capping off a journey that began last summer. It’s about the future of a budding space program that wants to take on more ambitious projects down the road, and a country that wants to become a new hub of tech and science innovation for Asia. Whether the Hope mission succeeds or not, its impact is already being felt.

The sciences

The Emirates Mars Mission is part of a larger investigation that planetary scientists have been pursuing for decades now, hoping to discover what transformed Mars from a wet, warm, potentially habitable world into a dry and cold one. A big piece of that puzzle is to figure out how Mars hemorrhaged most of its atmosphere so that its lakes and rivers evaporated over time.

The mission plans to study the atmosphere with an orbiter named Hope and its three key instruments. A camera will snap pictures of the planet using a slew of filters that restrict different wavelengths, helping scientists learn more about the water and ice content in the atmosphere or the nature of dust storms closer to the ground.

Hope will orbit Mars at a higher altitude than any previous Mars mission, allowing scientists to see half of the planet no matter where the orbiter is. Most other Mars orbiters move around the poles, so they are forced to observe locations at the same times of day with each pass overhead. Instead, Hope will orbit nearly parallel to the equator, so it will be able to watch locations at many different points throughout the day and see how things might change over time as the sun rises and sets. And its elliptical orbit will afford different ways of looking at the planet. At greater distances the spacecraft has a planet-wide view of Mars to observe global atmospheric changes over a single day, while at closer distances it can peer at specific regions to see how the atmosphere in those locations changes minute by minute, hour by hour.

“The riskiest phase”

Hope is set to rendezvous with Mars on Tuesday after a 27-minute thruster burn slows the spacecraft down from 121,000 kilometers per hour to closer to 18,000 km/h, allowing it to fall into the Martian orbit safely. That thruster burn is set to occur at around 7:30 p.m. UAE time (10:30 a.m. US Eastern time). The 11-minute lag in communication caused by the distance between the two planets, however, means that the burn is effectively an automated process—ground crews won’t really be able to control what is happening. They will mainly have to hope for the best as they receive intermittent updates.

“A lot of the engineering emphasis has been on making the [Mars orbital insertion] event completely autonomous,” says Pete Withnell, a scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who is working with the Hope mission. “During the event, we are observers. We get to see what’s happening, but we do not get to interact in real time.”

Mission control expects to receive a signal shortly after the burn that should indicate whether Hope has fallen into a Martian “capture orbit,” although if they miss this signal, they’ll have to wait another hour or so as Hope is eclipsed by Mars and waits to emerge from around the bend.

“This is the riskiest phase of the project,” says Omran Sharaf, project manager for the mission, adding that the propulsion system for the mission is “something you cannot really test on Earth 100%, because you cannot really simulate the environment.”

Should everything go as planned, the mission will transition from its “capture orbit” into its “science orbit” over the next few months, using that time to turn its instruments on and calibrate them for formal investigations. That transition should be completed by around the end of April or early May. According to Al Amiri, the team hopes to make the first science data available to the research community by early September.

More than a single mission

The risks are actually the point. One of the UAE’s biggest objectives through the Emirates Mars Mission has been to spur a young generation of scientists and engineers to get into space systems development in order to help the UAE enter the space economy. Like many other countries, the UAE wants to capitalize on the rise of small-spacecraft development and “create new business ventures in space,” says Al Amiri. She says she has witnessed a swell of enthusiasm among science and engineering students, who are now taking the idea of entering the space industry seriously.

Sharaf explains that some of the mission’s hardware was developed and manufactured by UAE companies. “It was a very good kind of test platform for us to understand the gaps that we have within our ecosystem and how we can design a program for our future missions which better integrates the private sector,” he says.

And it made sense to try for Mars rather than a high-tech demo in Earth’s orbit or even a mission to the moon. “It was a risky approach,” says Sharaf. “But as a young nation, we need to catch up. When it comes to technology and science, the learning curve is not really linear—it’s very exponential. It becomes much more difficult to catch up in the future. And this is why we’ve started to go with a Mars shot.”

When asked what a failed orbital insertion would mean for both the Hope mission and the UAE space program as a whole, Al Amiri’s answer was simple: “We will continue.” The “wild experiment,” as she calls it, has already set the ball rolling.