Bacteria-Laden Mosquitoes May Be the Cheapest Way to Stop Dengue and Zika

The health foundation of Microsoft billionaire Bill Gates is in talks with Latin American governments and scientists over plans to spread hundreds of millions of mosquitoes that are unable to transmit dengue fever and Zika virus.

The discussions include a proposal by scientists in Medellín, Colombia, to spend $16 million to try to protect the city’s three million people with the new breed of mosquitoes.

The idea being promoted by Gates is to release mosquitoes infected with a bacterium, Wolbachia pipientis, that prevents them from transmitting viruses such as dengue or Zika when they bite people.

The mosquito breed was created by scientists at Monash University in Australia and has been tried in tests in Australia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Rio de Janeiro as part of a dengue-eradication program on which Gates has already spent $40 million.

Fil Randazzo, a deputy director with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in Seattle, says the foundation is ready to give financial support to regions that want to expand the tests. “The early-phase research has yielded very promising results,” he says, although he cautions that “we can’t say how effective it is with any certainty.”

Scientists working with the Gates-funded mosquitoes say new technology may prove to be both very effective and very cheap. “Things look favorable,” says Ivan Dario Velez Bernal, director of the tropical disease program at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, who has led a pilot test in that city. “It’s more economical than insecticides. I think this is the least expensive by an enormous difference.”

Wolbachia is found in about half of all insects and stops the spread of some viruses, though precisely how isn’t known.

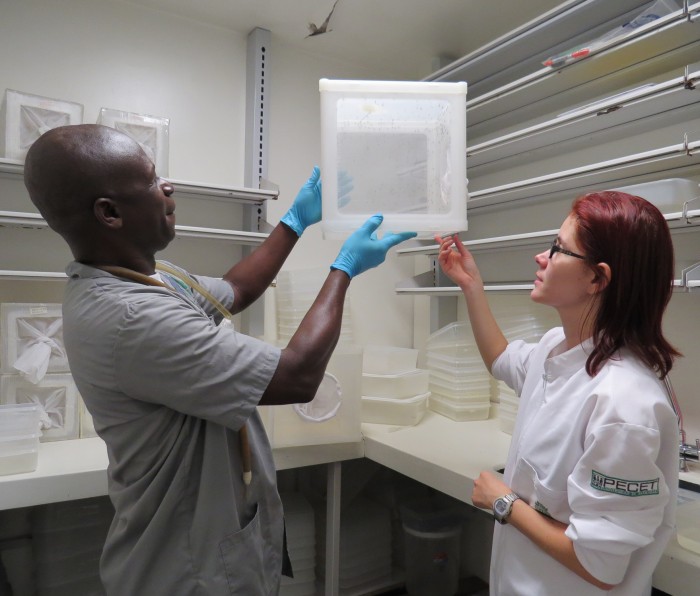

The mosquito that mostly spreads dengue, Aedes aegypti, doesn’t naturally carry the bacteria. So researchers had to inject bacteria obtained from fruit flies into mosquito embryos to establish mosquitoes whose cells harbor them.

“We don’t have to keep injecting it after that—it’s inherited,” says Scott O’Neill, the insect expert at Monash University who leads the Gates dengue program. “We are projecting a cost of $1 a person to implement it in cities, because we only apply it once over a period of months and it sustains itself.”

Using the mosquitoes as a public health tool means releasing millions of them out of doors so that eventually all local mosquitoes end up carrying the bacteria. In Australia, says O’Neill, it took 14 staffers one year to distribute mosquitoes over a 40-square-kilometer area, but since then local transmission of dengue has stopped.

The technology could have advantages over other strategies. One Brazilian city has been testing transgenic mosquitoes being commercialized by the company Oxitec. Those bugs suppress populations because they’ve been genetically modified so their offspring don’t live. But they need to be released year after year. Brazilian officials estimate that GM mosquitoes could cost $7 per person per year to prevent infections.

In Medellín, a small-scale field test of Wolbachia mosquitoes started in 2015, and Velez Bernal says in that district 80 percent of mosquitoes now carry the bacteria. Although there’s not yet enough data to say dengue cases have fallen off, he says that transmitting dengue “would be very hard” now that the bugs have been altered.

Velez Bernal says the Ministry of Health, in Bogotá, is now considering a $16 million plan to release the mosquitoes across all of Medellín and some outlying districts, which he says Gates has agreed to help pay for. “We are looking at the logistics of scaling it up,” he says. He estimates for the plan to work, the city will need to release about two mosquitoes per household each week for 20 weeks in order to establish the infection. “For all of Medellín, we’ll need a million mosquitoes a week,” he says.

Altogether in Colombia, about 35 million people live in areas where the Aedes mosquito is a threat.

Colombia has been hard hit by dengue, and more recently by the Zika virus. The country had 43,228 dengue cases in 2014, and its health ministry estimates there have been 35,000 Zika cases since last year, though the true number could be far higher.

O’Neill says he’s in a hurry to see the technology used, but that everything depends on the affected countries themselves. “It needs to have government support,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.