A New Focus for Light

Researchers trying to make high-capacity DVDs, as well as more-powerful computer chips and higher-resolution optical microscopes, have for years run up against the “diffraction limit.” The laws of physics dictate that the lenses used to direct light beams cannot focus them onto a spot whose diameter is less than half the light’s wavelength. Physicists have been able to get around the diffraction limit in the lab–but the systems they’ve devised have been too fragile and complicated for practical use. Now Harvard University electrical engineers led by Kenneth Crozier and Federico Capasso have discovered a simple process that could bring the benefits of tightly focused light beams to commercial applications. By adding nanoscale “optical antennas” to a commercially available laser, Crozier and Capasso have focused infrared light onto a spot just 40 nanometers wide–one-twentieth the light’s wavelength. Such optical antennas could one day make possible DVD-like discs that store 3.6 terabytes of data–the equivalent of more than 750 of today’s 4.7-gigabyte recordable DVDs.

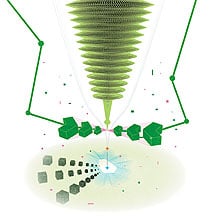

Crozier and Capasso build their device by first depositing an insulating layer onto the light-emitting edge of the laser. Then they add a layer of gold. They carve away most of the gold, leaving two rectangles of only 130 by 50 nanometers, with a 30-nanometer gap between them. These form an antenna. When light from the laser strikes the rectangles, the antenna has what Capasso calls a “lightning-rod effect”: an intense electrical field forms in the gap, concentrating the laser’s light onto a spot the same width as the gap.

“The antenna doesn’t impose design constraints on the laser,” Capasso says, because it can be added to off-the-shelf semiconductor lasers, commonly used in CD drives. The team has already demonstrated the antennas with several types of lasers, each producing a different wavelength of light. The researchers have discussed the technology with storage-device companies Seagate and Hitachi Global Storage Technologies.

Another application could be in photolithography, says Gordon Kino, professor emeritus of electrical engineering at Stanford University. This is the method typically used to make silicon chips, but the lasers that carve out ever-smaller features on silicon are also constrained by the diffraction limit. Electron-beam lithography, the technique that currently allows for the smallest chip features, requires a large machine that costs millions of dollars and is too slow to be used in mass production. “This is a hell of a lot simpler,” says Kino of Crozier and Capasso’s technique, which relies on a laser that costs about $50.

But before the antennas can be used for lithography, the engineers will need to make them even smaller: the size of the antennas must be tailored to the wavelength of the light they focus. Crozier and Capasso’s experiments have used infrared lasers, and photolithography relies on shorter-wavelength ultraviolet light. In order to inscribe circuitry on microchips, the researchers must create antennas just 50 nanometers long.

Capasso and Crozier’s optical antennas could have far-reaching and unpredictable implications, from superdense optical storage to superhigh-resolution optical microscopes. Enabling engineers to simply and cheaply break the diffraction limit has made the many applications that rely on light shine that much brighter.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.