Stretchable Silicon

These days, most electronic circuitry comes in the form of rigid chips, but devices thin and flexible enough to be rolled up like a newspaper are fast approaching. Already, “smart” credit cards carry bendable microchips, and companies such as Fujitsu, Lucent Technologies, and E Ink are developing “electronic paper” – thin, paperlike displays.

But most truly flexible circuits are made of organic semiconductors sprayed or stamped onto plastic sheets. Although useful for roll-up displays, organic semiconductors are just too slow for more intense computing tasks. For those jobs, you still need silicon or another high-speed inorganic semiconductor. So John Rogers, a materials scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, found a way to stretch silicon.

Stretchable Silicon

Key players

Stephanie Lacour – Neuro-electronic prosthesis to repair damage to the nervous system at University of Cambridge, England; Takao Someya – Large-area electronics based on organic transistors at University of Tokyo; Sigurd Wagner – Electronic skin based on thin-film silicon at Princeton University

If bendable is good, stretchable is even better, says Rogers, especially for high-performance conformable circuits of the sort needed for so-called smart clothes or body armor. “You don’t comfortably wear a sheet of plastic,” he says. The potential applications of circuitry made from Roger’s stretchable silicon are vast. It could be used in surgeons’ gloves to create sensors that would read chemical levels in the blood and alert a surgeon to a problem, without impairing the sense of touch. It could allow a prosthetic limb to use pressure or temperature cues to change its shape.

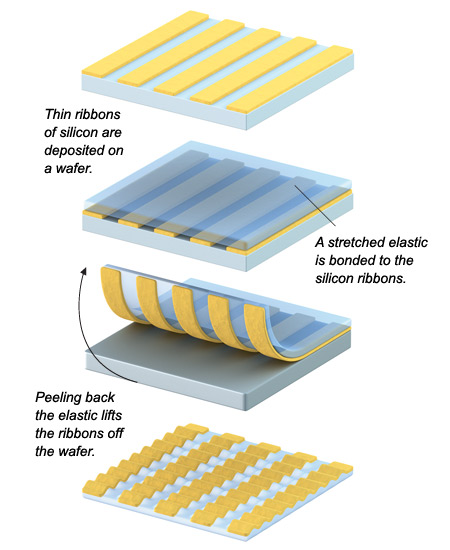

What makes Rogers’s work particularly impressive is that he works with single-crystal silicon, the same type of silicon found in microprocessors. Like any other single crystal, single-crystal silicon doesn’t naturally stretch. Indeed, in order for it even to bend, it must be prepared as an ultrathin layer only a few hundred nanometers thick on a bendable surface. Rogers exploits the flexibility of thin silicon, but instead of attaching it to plastic, he affixes it in narrow strips to a stretched-out, rubber-like polymer. When the stretched polymer snaps back, the silicon strips buckle but do not break, forming “waves” that are ready to stretch out again.

Rogers’s team has fabricated diodes and transistors – the basic building blocks of electronic devices – on the thin ribbons of silicon before bonding them to the polymer; the wavy devices work just as well as conventional rigid versions, Rogers says. In theory, that means complete circuits of the sort found in computers and other electronics would also work properly when rippled.

Rogers isn’t the first researcher to build stretchable electronics. A couple of years ago, Princeton University’s Sigurd Wagner and colleagues began making stretchable circuits after inventing elastic-metal interconnects. Using the stretchable metal, Wagner’s group connected together rigid “islands” of silicon transistors. Although the silicon itself couldn’t stretch, the entire circuit could. But, Wagner notes, his technique isn’t suited to making electrically demanding circuits such as those in a Pentium chip. “The big thing that John has done is use standard, high-performance silicon,” says Wagner.

Going from simple diodes to the integrated circuits needed to make sensors and other useful microchips could take at least five years, says Rogers. In the meantime, his group is working to make silicon even more flexible. When the silicon is affixed to the rubbery surface in rows, it can stretch only in one direction. By changing the strips’ geometry, Rogers hopes to make devices pliable enough to be folded up like a T-shirt. That kind of resilience could make silicon’s future in electronics stretch out a whole lot further.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.