Nuclear Reprogramming

Embryonic stem cells may spark more vitriolic argument than any other topic in modern science. Conservative Christians aver that the cells’ genesis, which requires destroying embryos, should make any research using them taboo. Many biologists believe that the cells will help unlock the secrets of devastating diseases such as Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis, providing benefits that far outweigh any perceived ethical harm.

Nuclear Reprogramming

Key players

George Daley – Studying nanog’s ability to reprogram nuclei at Harvard Medical Schoo; Kevin Eggan – Reprogramming adult cells using stem cells at Harvard University; Rudolf Jaenisch – Creating tailored stem cells using altered nuclear transfer (CDX2) at MIT

Markus Grompe, director of the Oregon Stem Cell Center at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, hopes to find a way around the debate by producing cloned cells that have all the properties of embryonic stem cells – but don’t come from embryos.

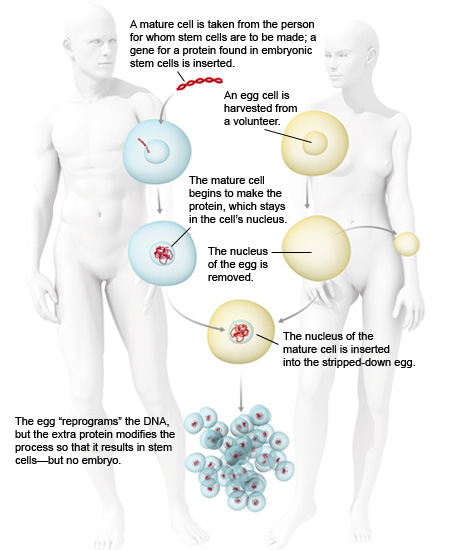

His plan involves a variation on the cloning procedure that produced Dolly the sheep. In the original procedure, scientists transferred the genetic material from an adult cell into an egg stripped of its own DNA. The egg’s proteins reprogrammed the adult DNA, creating an embryo genetically identical to the adult donor. Grompe believes that by forcing the donor cell to produce a protein called nanog, which is normally found only in embryonic stem cells, he can alter the reprogramming process so that it never results in an embryo. Instead, it would yield a cell with many of the characteristics of an embryonic stem cell.

Grompe’s work is part of a growing effort to find alternative ways to create cells with the versatility of embryonic stem cells. Many scientists hope to use proteins to directly reprogram, say, skin cells to behave like stem cells.

Others think smaller molecules may do the trick; Scripps Research Institute chemist Peter Schultz has found a chemical that turns mouse muscle cells into cells able to form fat and bone cells. And Harvard University biologist Kevin Eggan believes it may be possible to create stem cells whose DNA matches a specific patient’s by using existing stem cells stripped of their DNA to reprogram adult cells.

Meanwhile, researchers have tested methods for extracting stem cells without destroying viable embryos. Last fall, MIT biologist Rudolf Jaenisch and graduate student Alexander Meissner showed that by turning off a gene called CDX2 in the nucleus of an adult cell before transferring it into a nucleus-free egg cell, they could create a biological entity unable to develop into an embryo – but from which they could still derive normal embryonic stem cells.

Also last fall, researchers at Advanced Cell Technology in Worcester, MA, grew embryonic stem cells using a technique that resembles something called preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). PGD is used to detect genetic abnormalities in embryos created through in vitro fertilization; doctors remove a single cell from an eight-cell embryo for testing. The researchers separated single cells from eight-cell mouse embryos, but instead of testing them, they put each in a separate petri dish, along with embryonic stem cells. Unidentified factors caused the single cells to divide and develop some of the characteristics of stem cells. When the remaining seven-cell embryos were implanted into female mice, they developed into normal mice.

Such methods, however, are unlikely to resolve the ethical debate because, in the eyes of some, they still endanger embryos. Grompe’s approach holds out the promise of unraveling the moral dilemma. If it works, no embryo will have been produced – so no potential life will be harmed. As a result, some conservative ethicists have endorsed Grompe’s proposal.

Whether it is actually a feasible way to harvest embryonic stem cells remains uncertain. Some are skeptical. “There’s really no evidence it would work,” says Jaenisch. “I doubt it would.” But the experiments Grompe proposes, Jaenisch says, would still be scientifically valuable in helping explain how to reprogram cells to create stem cells. Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientist George Daley agrees. In fact, Daley’s lab is also studying nanog’s ability to reprogram adult cells.

Still, many biologists and bioethicists have mixed feelings about efforts to reprogram adult cells to become pluripotent. While they agree the research is important, they worry that framing it as a search for a stem cell compromise may slow funding – private and public – for embryonic-stem-cell research, hampering efforts to decipher or even cure diseases that affect thousands of desperate people. Such delays, they argue, are a greater moral wrong than the loss of cells that hold only the potential for life.

Many ethicists – and the majority of Americans – seem to agree. “We’ve already decided as a society that it’s perfectly okay to create and destroy embryos to help infertile couples to have babies. It seems incredible to me that we could say that that’s a legitimate thing to do, but we can’t do the same thing to help fight diseases that kill children,” says David Magnus, director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.