Power to the people

There’s a growing fear among many American workers that they’re about to be replaced by technology, whether that’s a robot, a more efficient computing system, or a self-driving truck. It’s an anxiety palpable in pop culture, national polls, and news stories; on presidential debate stages; even in the halls of the Institute. “People are coming to MIT and literally saying, ‘I need MIT to tell me—is a robot going to take my job?’” says David Mindell, PhD ’96, a professor of aero-astro and the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing.

To address the anxiety, a new MIT report, “The Work of the Future: Shaping Technology and Institutions,” explores the legacy of technology in the American workplace to help us understand what lies ahead. No, robots aren’t about to take over all the work, but technological advances have devastated many middle-class jobs, contributing to record levels of inequality and significantly reduced social mobility. And if we don’t do anything, the future will be even worse.

The report is the first step in “finding a more coherent way to talk about these topics,” says Mindell, one of the co-chairs of the task force behind the report. “If MIT doesn’t have a voice on the subject, then who will?”

A broad task force for a big task

MIT president L. Rafael Reif first convened the Task Force on the Work of the Future in 2018. He wanted to help address what he describes as “the sense of powerlessness—the worry that automation is ‘coming to get us’ automatically,” and that no recourse is available, he said in September at a briefing announcing the report in Washington, DC. “It is up to those of us advancing new technologies to help make certain that they do not wind up damaging the society we intend them to serve.” The task force was made up of 18 faculty members from nearly a dozen departments, supported by an advisory board, a research board, and a number of staffers and graduate students.

Men without college degrees working full time made less per week on average in 2018 than they did in 1980.

President Reif charged the group with investigating the relationship between work and technology. Through surveys, case studies, historical analysis, and other research projects, task force members aim to restore some of that lost power to American workers—and offer guidance to the governments that serve them and the enterprises that depend on them.

The task force’s interim report makes clear from the outset that current American fears about how technology will affect the workforce are “neither misguided nor uninformed.” Indeed, they’re based firmly in real economic trends.

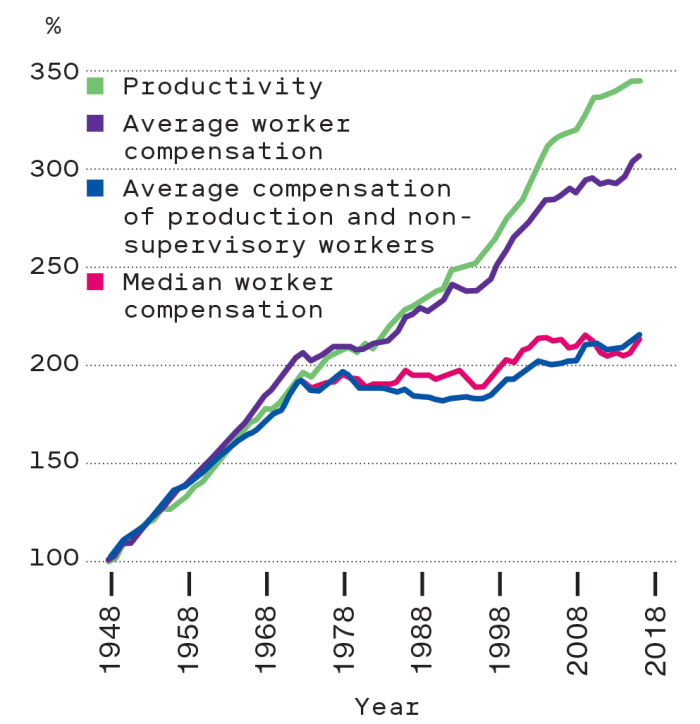

Over the last four decades, “ordinary software, computers, and information technology have transformed everyone’s work,” says Mindell. Partly as a result, US productivity—the measure of how efficiently the economy as a whole is using its resources—grew by 75% between 1973 and 2016. The report calls that “healthy,” although it is smaller than the increase during the first three decades after World War II, and the pace of growth has slowed considerably in the past decade and a half.

But the benefits have been unequally distributed. As productivity rose over those 44 years, the median wage increase was a mere 11%. “Productivity growth did not translate into shared prosperity,” the report explains, “but rather into employment polarization and rising inequality.” Indeed, income inequality has soared: in 1973, the top 1% of earners in the US accounted for 11.0% of national income while the bottom 50% had 20.3%. In 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, the top 1% earned 20.2%, while the bottom half had just 12.6%.

A major factor in whether automation helps or harms a particular person professionally is education, Mindell says—and those who lack a four-year college degree typically lose out.

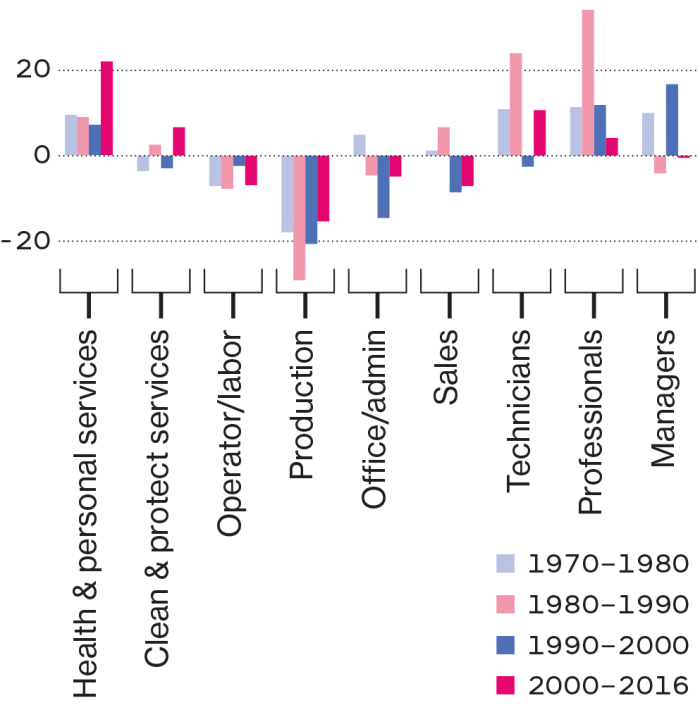

Technology tends to make workers in high-skill jobs—the term economists use to refer to jobs that require a lot of education, experience, and abstract thinking—even more productive. For example, an architect can use a design program to create blueprints more quickly, thus completing commissions faster and earning more money. But at the other end of the spectrum, technology currently isn’t much help when it comes to performing many so-called low-skill jobs, such as those of retail clerks and cleaners. These jobs require physical dexterity, face-to-face communication, visual recognition, and situational adaptability—things that today’s computers are generally terrible at but humans can do with relatively little training. So although most low-skill jobs remain safe from the threat of automation, few low-skill workers are reaping any of the benefits of technological innovation. In other words, as the report points out, “digitalization has had the smallest impact on the tasks of workers in low-paid manual and service jobs.”

Meanwhile, middle-skill jobs—those that require a significant amount of training but involve more repetitive tasks, including bookkeeping, clerical work, and many manufacturing jobs—can be done by machines. For that reason, many of these jobs are being automated away, or in some cases moved offshore. The result has been a stunning polarization of the workforce and hollowing out of the middle class: both high-wage and low-wage jobs have risen dramatically while in-between jobs have plummeted (see “Middle-class jobs are disappearing”). In the past, you might have been able to transition from a low-skill job to a high-skill job via one of those middle positions. Now, “if you fall on the wrong side of that [education] divide, you have a very hard time getting across it,” says Mindell.

This barrier to mobility has affected black and Hispanic people more than white people, and rural workers more than urban workers (although wage disparity is particularly dire in cities). And men have felt the impact more than women because they’ve held most of the routine manufacturing jobs that have been automated away. When these demographics compound, the consequences can be both broadly unfair and personally devastating: men without college degrees working full time actually made less per week on average in 2018 than they did in 1980, when adjusted for inflation.

Breaking down the #1 automation myth

Turns out there are more jobs than workers. The problem is, they don’t pay enough.

As we worry about work being automated away, the opposite problem is creeping up on us. “There’s a ton of focus on scarcity of jobs,” says economics professor and task force co-chair David Autor. “But in reality we will face a scarcity of workers.”

The number of open jobs in America first outpaced the number of available workers in January of 2018. Many of these are “low-skill” jobs—those that can be done without much special training but often don’t pay a living wage. If trends continue, this problem will compound over the next two decades. Here’s why:

1. The population is aging.

The US Census Bureau predicts that by 2034, there will be more Americans over 65 than under 18. This means fewer people who are able to do physically demanding jobs, like food service or factory floor work. It also means increasing demand for workers in health care.

2. The jobs aren’t attractive.

Some career tracks that used to seem like a safe bet no longer do. A massive downturn in manufacturing over the past decade has made it harder for factories to recruit younger workers, says Institute Professor and political scientist Suzanne Berger, who serves on the task force. “What family wants their child to go into a field where there have been 6 million jobs lost?” she asks. Meanwhile, workers in other sectors, including restaurants and catering, are quitting at high rates—likely because they’re fed up with low pay and bad working conditions. And more and more people are going to college, hoping to start their careers higher up the ladder.

3. Immigration rates are falling.

In 2016, 25% of construction workers were immigrants, and percentages in the hotel and lodging, food service, and home health care sectors are similar. But the annual increase in the US immigrant population is slowing. After having risen steadily by 400,000 to 1,000,000 per year since 2010, it went up by only 203,000 between 2017 and 2018—the smallest increase since 2007-’08, the first year of the Great Recession, according to an analysis by the Brookings Institution.

4. The technology isn’t there yet.

If it could perform low-skill work and free people to pursue other careers, “automation might actually be a friend,” says task force executive director Elisabeth Reynolds, PhD ’10. But we’re not there yet. In general, “robots are coming more slowly than people predicted,” says task force co-chair David Mindell, PhD ’96, professor of aero-astro and of the history of engineering and manufacturing, and it’s still very hard to design machines that can perform complicated physical tasks. Just look at self-driving cars, and their perpetually postponed arrival date. “We shouldn’t be worried about running out of work,” says Autor. “We should be worried about finding ways to make work secure and rewarding for the people who are available to do it.”

The increase in technology has thwarted the aspirations of many Americans: whereas 92% of workers born in 1940 earned more than their parents, only 50% of those born in 1980 can say the same. For many, the American dream is getting further out of reach.

Not inevitable

The increased inequality and decreased opportunities for many represent a dramatic reversal from much of the 20th century. From 1945 to 1973—a stretch that saw the introduction of the bar code, the microwave oven, and UNIX—worker earnings and productivity both doubled. During that time, “we managed technological progress and shared prosperity extremely effectively,” says David Autor, the Ford Professor of Economics and a co-chair of the task force.

“If we had written this report in 1970, we would have said, ‘Actually, it works out great,” Autor says. But “the lesson of the past four decades is that technological progress doesn’t lift all boats.”

So what’s different now? One change is the type of innovation. Although productivity is still generally on the upswing, computerization—the defining technology of our era—hasn’t been as effective over the last decade at increasing it as the chief innovation types of other eras, like industrialization and mechanization.

What’s more, automation and computers are often simply replacing workers rather than complementing them or creating further opportunities. Although these inventions might benefit the companies that deploy them, their benefits don’t spill over into the labor market as a whole. Instead, they help concentrate gains in the hands of a few (see “Going beyond the so-so”).

But our own national priorities, as expressed through policy, don’t help matters. Companies in the United States have stripped away many workers’ rights and have become solely focused on increasing value for shareholders. Unions, meanwhile, have “atrophied,” the report says. The federal minimum wage has fallen over the past decade when adjusted for inflation. While new forms of worker organizing have arisen, none have been able to reverse the trend of focusing almost exclusively on shareholders at the expense of workers’ interests (see “Tech-savvy labor activism”).

As the report points out, most other market economies “broadly accept (and often enforce) the notion that employees and communities are among the legitimate stakeholders to whom a firm must be responsive.” The task force believes the United States should move in this direction, although it isn’t yet sure on the details.

Over 90% of workers born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents, while only 50% of those born in 1980 can say the same.

Developed countries with pro-worker policies aren’t experiencing nearly as much income polarization, even as automation advances. Sweden, for example, has more robots per capita than the US, but it also has robust unions and a strong welfare system. Wages are still high, inequality is low, and most citizens aren’t worried. They trust that “if technology benefits productivity, then most people will benefit,” says Autor.

Meanwhile, because US institutions haven’t worked to blunt the disruptive impacts of new technologies, American workers feel they’ve been left to fend for themselves in an economy that favors shareholders. “The cowboy capitalism model of the US is showing its limitations,” says Autor.

Beyond technology

Most of the report’s suggestions are focused on fixing the imbalance between those helped and hurt by the new economy. This boils down to investing more in workers—providing them with educational opportunities and political support, and restructuring our laws, our institutions, and even our ideas of who should benefit from progress (see “Where are the robots?”). “Without taking any steps policy-wise, we will just continue to see the situation we’re in worsen,” says the task force’s executive director, Elisabeth Reynolds, PhD ’10.

We’ve succeeded in this type of challenge before: as the report points out, the US responded to industrialization over the first half of the 20th century by introducing free public high school, in order to outfit young people with the skills they would need to prosper as agrarian employment shrank.

The task force recommends a similar investment in education today, especially for workers without college degrees. Community colleges, vocational training programs, apprenticeships, and affordable online education can all help bridge the opportunity gap. So could offering employers tax incentives to invest in skill training for their workers.

The report also encourages investment in the right kinds of automation—those that will complement workers rather than replace them, boost overall productivity rather than concentrate gains within companies, and keep the US at the forefront of technological trends like AI and machine learning (see “Congratulations—it’s a bot!”).

The task force is now delving into research that will inform more specific policy recommendations; it plans to follow up this interim report with a final report about a year from now. Areas the members hope to explore further include how artificial intelligence will affect the workforce, why productivity isn’t growing as fast as it used to, and how demographic changes will shift the needs of the labor market.

Their proposed solutions beget even more questions: Which technologies should we be investing in? How can we give workers a voice? What’s the best way to teach adults new skills? And how can the people of MIT—as they innovate, automate, and help shape the world—make sure their own work is addressing, rather than exacerbating, existing divides?

“Technology is a tool,” Reynolds says. “It’s a tool that we shape and figure out how to use.” Progress may not inevitable, but it’s still possible. And building a future that benefits everyone is work only humans can do.

Where are the robots?

Despite dire predictions, robots haven’t invaded most factories.

One of the most vivid images of the supposedly robot-filled future is that of the “lights-out” factory. It’s called that because “when you walk into the factory, it’s dark,” says Institute Professor Suzanne Berger, a political scientist and a member of the task force. “There’s nobody working there except robots, so they don’t need the lights on.”

Only three years ago, Oxford University researchers and McKinsey consultants alike were forecasting, if not lights-out factories, then something close. “The predictions about the impact of robots on jobs in manufacturing were extraordinarily pessimistic,” says Berger.

From 2009 through 2012, Berger co-chaired the Production in the Innovation Economy (PIE) project, which brought her to small and medium-size factories across the country to learn how they were incorporating new ideas. For the Task Force on the Work of the Future, she and her team began returning to some of those factories in 2019, this time hoping to learn about the effects of automation. And after reading those predictions, they braced for bad news. Would they encounter mass layoffs? Stressful reorganizations?

Instead, they found something Berger calls “astonishing”: Of the three dozen companies they revisited, only two had purchased robots.

Worker displacement was far from the firms’ minds. Most had the opposite problem. For example, although almost every company employed more people than it had seven years before, some were starting to have trouble finding even workers without any special skills (see “Breaking down the #1 automation myth,” above).

Others wanted robots but didn’t have large enough orders or the long-term contracts to justify getting them. Many US firms with under 500 employees serve as suppliers for larger ones, making things like pipes or screws. They usually can’t predict exactly what they’ll be asked to provide. “The robots that are available today are not tremendously flexible,” says Berger. It doesn’t make sense for a small company to buy one only to have it languish because it’s geared to the wrong task.

Still other companies didn’t have the support they needed to adopt that kind of innovation. In the earlier study for PIE, Berger’s team found that companies in Germany that wanted to expand their offerings or break into a new sector were able to take advantage of public funds, outside experts, and training programs for their workers. For example, one German company that originally made car parts used those resources to successfully move into medical devices.

In the US, though, small and medium-size factories were on their own. Considered too risky to lend to, they “could draw on nothing except whatever they had in their own pockets,” says Berger.

When Berger’s team revisited an Arizona metalworking company in 2020, it had purchased two robots. A welding robot had done “almost nothing” for seven years. And it had taken 22 months to get a robot used in a nickel-plating operation functioning. Why so long? “They had to figure out how to do it themselves with their own people,” she says.

Likewise, at the only other company that had managed to buy a robot, the worker in charge of it worried that he’d never get it working until he found tutorials online that helped him eventually figure it out. Now, he’s glad it’s there—and the lights are still on.

The real challenges, Berger says, have to do with raising wages, supporting innovation in small and medium firms, and teaching future generations of manufacturing workers new skills. “The hype about robots, and the dangers of tech taking over the workplace, have really focused our attention in the wrong place.”

Going beyond the so-so

Sometimes, automation just makes things worse.

Have you ever gotten stuck at a grocery store self-checkout kiosk because you couldn’t figure out how to pay for your bananas? If so, you had one of the defining experiences of our current age: you were stymied by a “so-so technology.”

The term was coined last year by Institute Professor and economist Daron Acemoglu and Boston University’s Pascual Restrepo to refer to innovations that displace workers without providing much of an increase in productivity. “Everybody hates them, for good reason,” says Acemoglu.

What makes a technology so-so? As Acemoglu explains, the best cases of automation are good both for customers and for the workforce. Take a familiar machine, the ATM. ATMs took over certain tasks that bank tellers used to do—hence the name “automated teller machine.” But they didn’t put those people out of work. From the mid-1980s, when ATMs started spreading rapidly, to 2010, the number of human bank tellers actually increased.

Why? Because the machines significantly increase productivity. As banks save money on this one task, they can expand into other areas, Acemoglu says: “They’ll open more branches. They’ll deal with additional problems, and offer new services.”

In other cases, though, automation will save a bit of money for the company but not improve things overall. Instead, like self checkouts, “they shift the cost to the consumer,” he says. That’s when you have a so-so technology on your hands. Another example is the recent wave of automated customer service technologies—the chatbots and computerized responders that now “pick up” the phone when you call a large retailer, hospital, or airline. Where trained workers once used their knowledge and ingenuity to help customers out, those customers now have to navigate a maze of phone menus in an attempt to solve their own problems. They are worse off, and call center workers are out of a job.

Acemoglu’s observations make him wary of how we’ll approach the AI revolution. “You can use AI to completely restructure classrooms, [empower] teachers, and make teaching more interactive,” he says. But at the moment—thanks to the way we tend to approach automation, as well as tax incentives that make it easier to buy equipment than to hire workers—“we’re much more likely to use AI to get rid of teachers.”

So how do we avoid the so-so? Acemoglu thinks MIT should be ready to “judge the social impacts” of the technology it puts out into the world—one of the very things the new MIT Schwarzman College of Computing aims to teach students to do.

Congratulations—it’s a bot!

This AI scheduling system isn’t stealing jobs—it’s freeing up nurses to focus on difficult issues.

Pop quiz: you’ve got 20 patients, 20 rooms, and 10 nurses. You have to assign each patient to the right room, and each nurse to the right patient, based on criteria that are constantly changing. And it’s urgent, because the patients are giving birth.

This is what nurse managers in delivery wards have to deal with on an hourly basis. Mathematically speaking, they’re “doing a job that’s more computationally complex than that of an air traffic controller,” says Julie Shah ’04, SM ’06, PhD ’11, an associate professor in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and a task force member. “And they’re doing it without any decision support.”

In 2014, Shah and some collaborators set out to change that. Working with nurses at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, they created an AI system aimed at relieving some of the cognitive load, without replacing any employees. While the project is still at the proof-of-concept stage, it is promising enough for Shah and the project’s leader—her former student Matthew Gombolay, SM ’13, PhD ’17, now an assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology—to make plans for scaling it up.

As the head of CSAIL’s Interactive Robot Group, Shah develops machines and systems with the goal of enhancing human capabilities. In manufacturing settings, this means creating robots that track what people are doing and predict their next moves. This enables their human coworkers to do their jobs naturally, rather than trying to act like robots themselves.

On the labor floor at Beth Israel Deaconess, the problem was a little different. It takes about a decade of practice for a nurse manager to effectively schedule a floor, says Shah. Novices shadow veterans, learning as they go.

The team designed its AI system so that it could also “apprentice” in this way. They created a virtual version of the labor floor, with algorithmically generated patients, births, preferences, and complications, and had doctors and nurses do a day of “work” inside it, making the same decisions they would in real life. By watching accomplished nurse managers as they went about their simulated work, the AI learned to emulate nurse decision-making.

The team then trained the AI to read the handwritten whiteboard that the nurses use to keep track of what’s going on. By the time it had finished training, the AI was able to take in information from the whiteboard and present suggestions on a computer screen about things like scheduling and staff allocation. Medical professionals agreed with those suggestions 90% of the time. (Another version of the AI was housed in a humanoid robot called Nao, which spoke its suggestions aloud. In one video, for example, a nurse asks the robot to look at the whiteboard and suggest “a good decision.” The robot replies: “I recommend placing a scheduled Cesarean section patient in room five.”)

Quickly accepting some of the AI’s suggestions freed the nurses up to spend more time on the tougher calls. And they didn’t for a moment feel threatened by their new coworker. “Their starting point was ‘We know AI cannot do our jobs,’” says Shah. “‘That’s just not possible. So how can you help us?’”

Tech-savvy labor activism

Workers are turning to technology to organize and advocate.

Technology isn’t just changing how people work. It’s also affecting labor activism—providing new ways for workers to communicate, organize, and fight for change. Gabriel Nahmias (above), a PhD student in MIT’s political science department, is studying these emerging forms of collective action and producing a white paper on the subject for the task force.

For example, domestic employees who work directly for families often lack some of the safeguards available to other types of workers. But technology can fill in some of those gaps. Take the digital contract-making tools created by the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which help babysitters, maids, and gardeners draw up official agreements with their employers. “If something goes wrong, you have some protections,” says Nahmias.

Workers also now congregate in online spaces that Nahmias calls “digital union halls.” Over the past few years, Uber drivers across the world have created city-specific WhatsApp groups to share advice and concerns. Sometimes texting turns into action: in 2018, truckers in Brazil who were upset about rising diesel prices used the platform to set up a 10-day strike. People are “using this new technology to organize and coordinate behavior in a way that they couldn’t before,” says Nahmias.

People are also organizing for new reasons. In recent years, “tech workers have done a lot of solidarity strikes and a lot of organizing for social outcomes,” says Nahmias. In 2018, Google decided not to renew a contract to develop AI software for the Pentagon after 4,000 employees signed a petition and a dozen engineers quit. This past summer, nearly 10% of Wayfair employees walked off the job over the company’s contract with US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement to supply furniture for a migrant detention center.

Despite the decline in unions, these digital tools mean people are “organizing those who were left out, organizing in new ways, and organizing for new purposes,” says Nahmias. And far from being automated out, they’re beginning to use technology to regain their own autonomy.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.